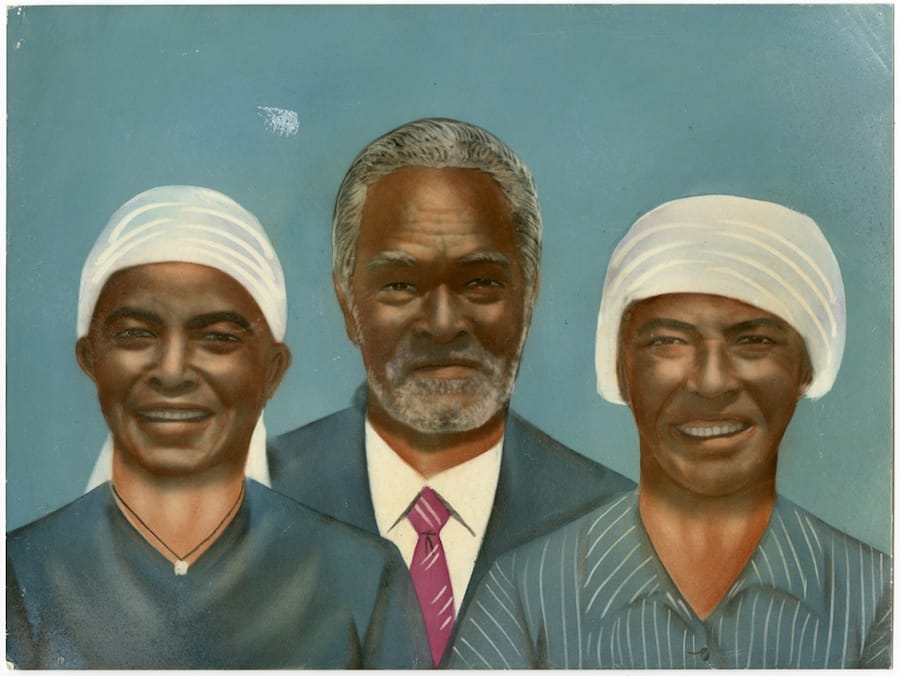

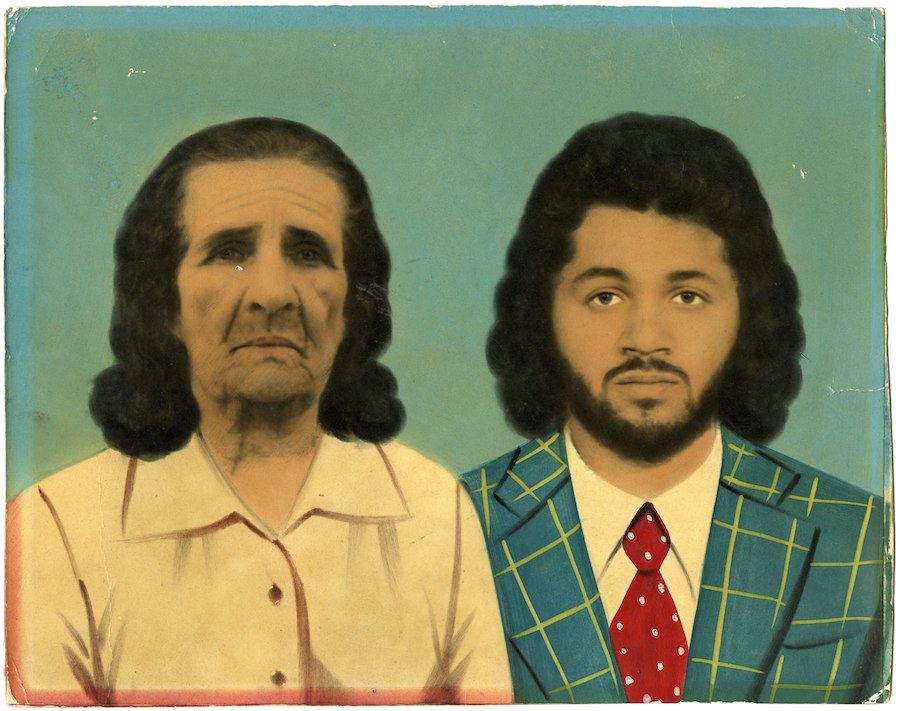

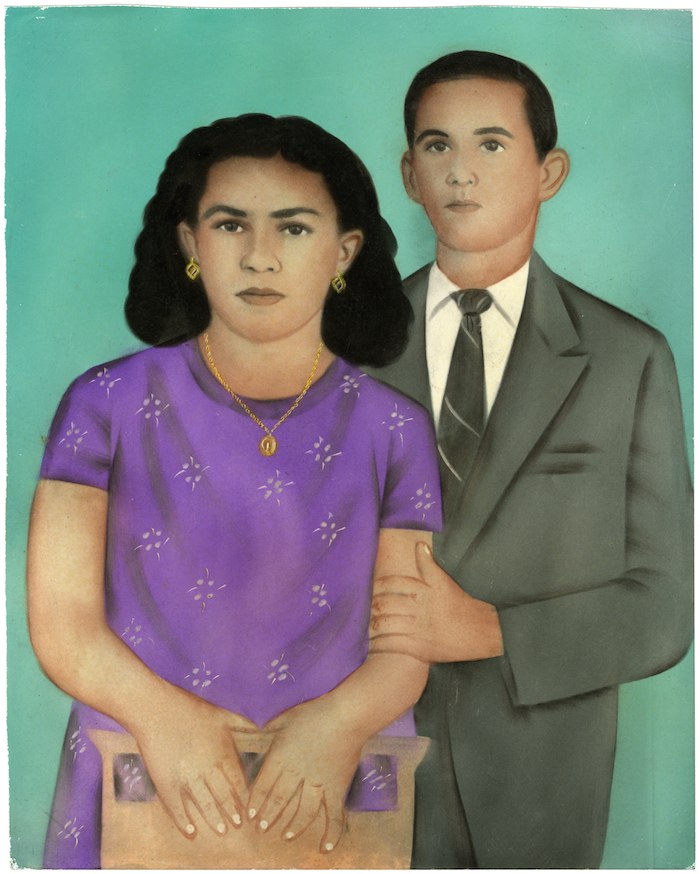

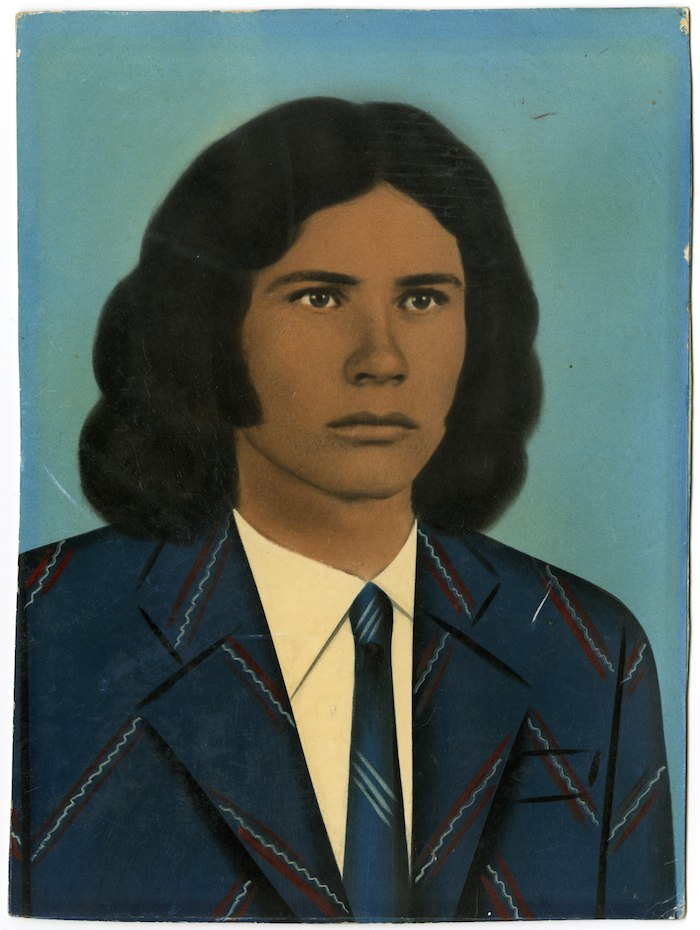

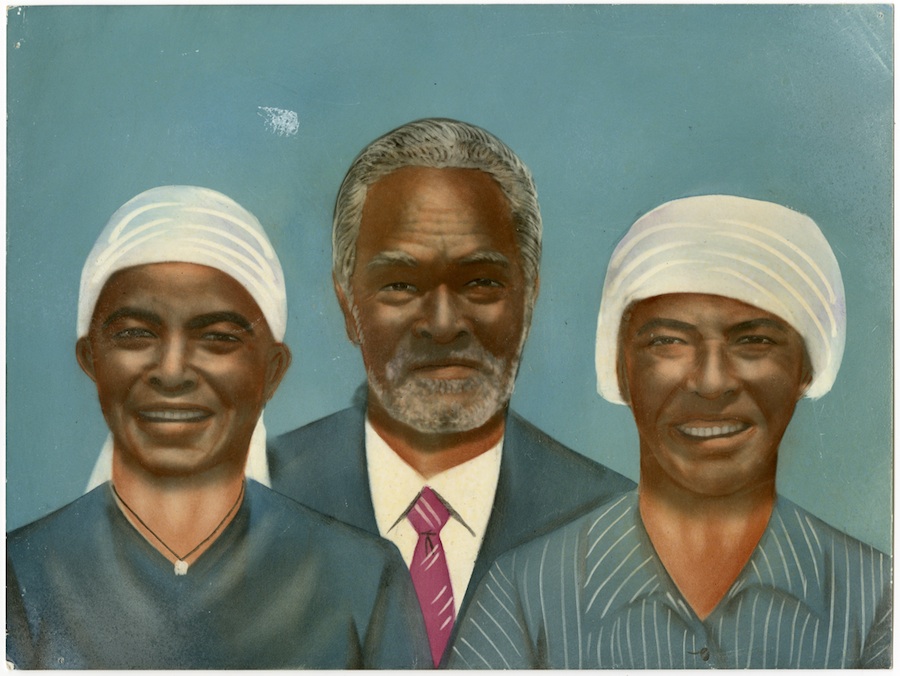

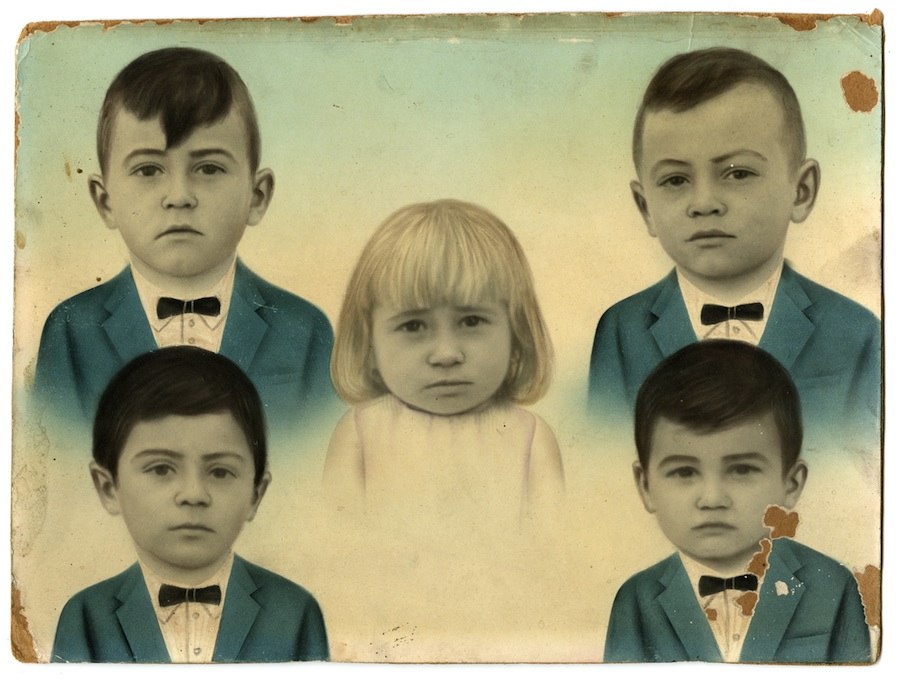

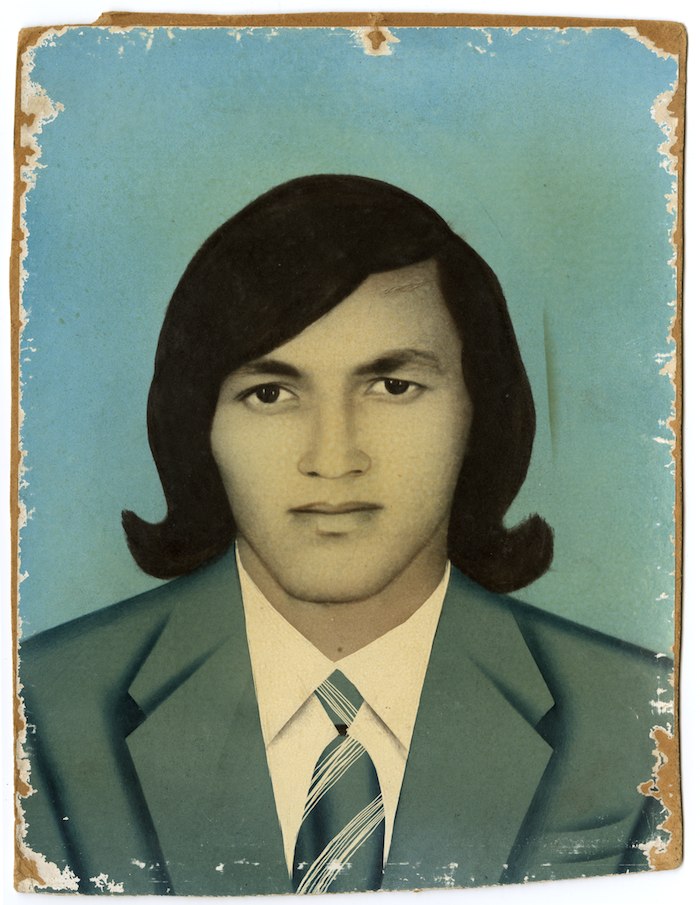

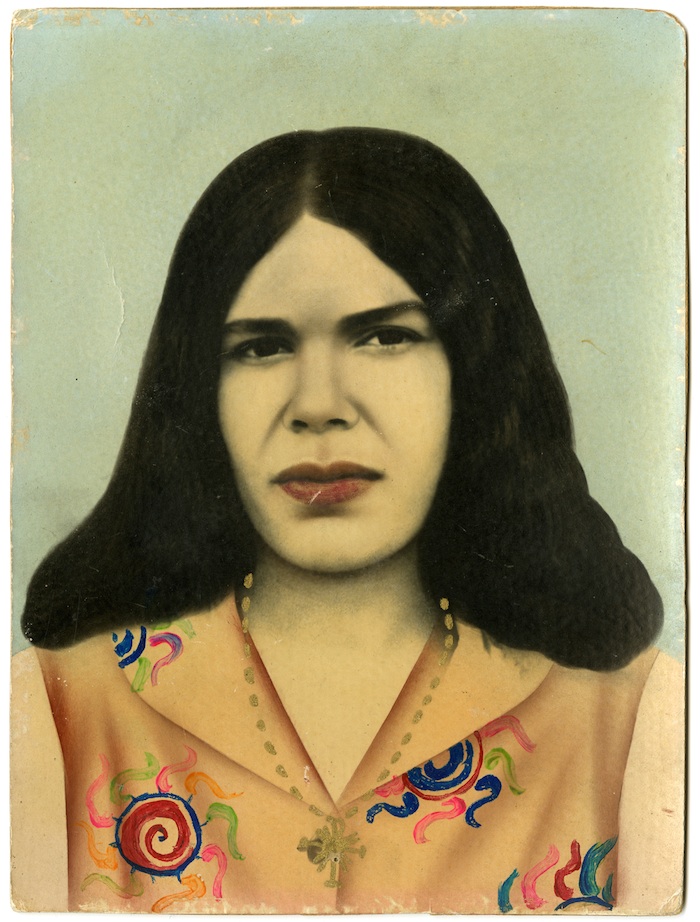

Retratos Pintados

From the late 19th century until the 1990s, retratos pintados (“painted portraits”) were common in rural northeastern Brazil: family portraits retouched to improve appearances.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

It’s easy to see why Martin Parr fell in love with historian Titus Riedl’s collection of hand-painted vernacular photographs from Brazil. (Parr wrote the introduction to Riedl’s recent book.) From the late 19th century until the 1990s, retratos pintados (“painted portraits”) were common in rural northeastern Brazil: family portraits retouched to improve appearances. They were acts of transformation, and could make your family members appear rich, healthy, and beautiful, even the dead ones. Riedl explains below how the tradition has largely died out, and why it’s been replaced with screensaver motifs. Read the interview ↓

Retratos Pintados is on show at Yossi Milo Gallery, New York, June 24 to Sept. 18, 2010. We highly recommend it. Retratos Pintados © Retratos Pintados, courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York.

Artist interview

When did you begin collecting these portraits? Do the retratos pintados continue?

In 1998-99, I was doing academic research about the memento mori (portraits of the dead) in northeast Brazil. That began my interest in vernacular photography and Brazilian popular culture and imagination. I am like a historian in that I’m interested in the preservation and documentation of cultural memory.

Since I began collecting, I have seen most of the [retratos pintados] offices close and the professionals give up their services.

How did the process work? If a family wanted to commission a portrait, who did they approach? Were painters and dealers widely available?

There were a lot of professionals participating in the portrait-making process, but the clients, in general, only had contact with a certain type of informal street trader, called bonequeiros, who usually did not even know the photo and painting processes involved. After traveling for days or weeks in rural areas, they carried the families’ original photographs, with some written annotations, to the bigger towns to hand over the materials to the puxadores (who enlarged the photographs in the photo labs) and the photo-painters. After a couple of weeks, the street sellers would travel back on the same route and return to the clients to deliver their photo-paintings.

Generally, the first approach would come from the seller looking for clients, and not the client looking for the painter’s services. Usually the paintings were created in improvised, hidden backyard offices without published addresses—like an entire informal economy.

But does the practice carry on?

The tradition of hand-colored photo-paintings has practically become extinct. There are some painters who know the art very well, but it is too difficult for them to find adequate materials. They can no longer find cheap black-and-white photo paper, or professionals to enlarge the photographs in domestic laboratories.

Some professionals continue the tradition in another way, commercializing the same type of images without hand-painting: by using a computer (using Photoshop) and domestic inkjet printers.

These new products are usually less sophisticated, and you can find subtle aesthetic changes; now it is common to add picturesque, postmodern backgrounds, like copies of phone cards, postcards, screensaver motifs, etc.

What does the act of painting on the photo mean to you? How is the photograph changed?

This kind of photo-art is very poetic, because you can manipulate the image and “better” your reality. This kind of representation has nothing to do with the verisimilitude usually attributed to photography. You can transform the portrait of a dead face to a living face. You can recreate family scenes. You can rescue absent family members and integrate them into a new scene. You can transform a poor dress into a rich dress. You can add jewelry and all kinds of similar attributes.

But the photographic act and the popular imagination are changing in radical ways—now, a certain kind of ritual aspect and ceremony connected with the photographic act is lost. In the past, photography required serenity and respect. The painted photo granted authority and social prestige to the owner, but now it has become a very banal act.