Salix Polaris

Portraits of scientists, explorers, and other “professional dreamers” who have found their way to the North Pole.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

The Morning News: How did this book begin?

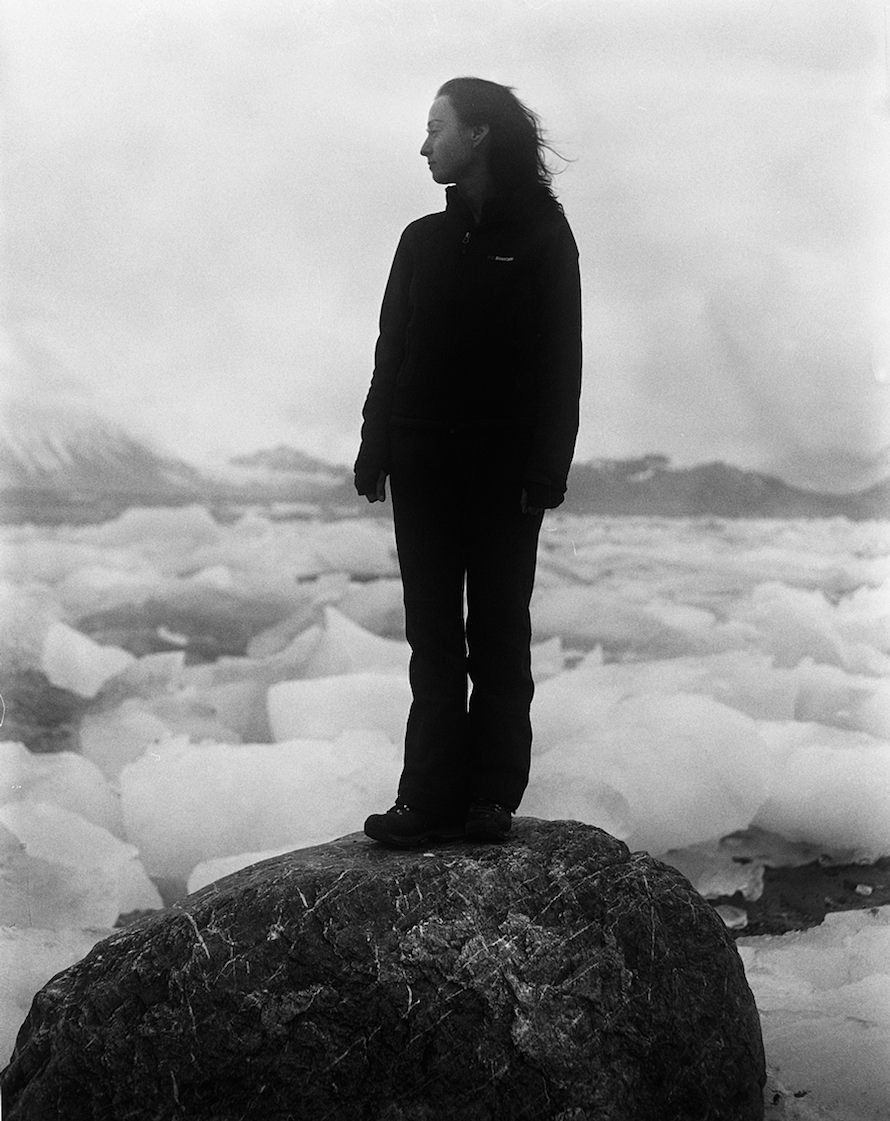

Anka Sielska: I first thought about this journey in 2009, when I watched Werner Herzog’s Encounters at the End of the World. I became fascinated with the people who, looking for their place in the world, “fell” all the way down to the South Pole. One of the characters, Stefan Pashov, a philosopher working as a digger-driver in the polar station, called these people “professional dreamers.” At first, I had not thought about a book, all I wanted was to go to the Pole and photograph. Beside the people, I was attracted to the landscape, the emptiness I assumed must intensify the feeling of isolation. Moreover, I have always been afraid of cold and open spaces, and taking photos helps me tame my fears.

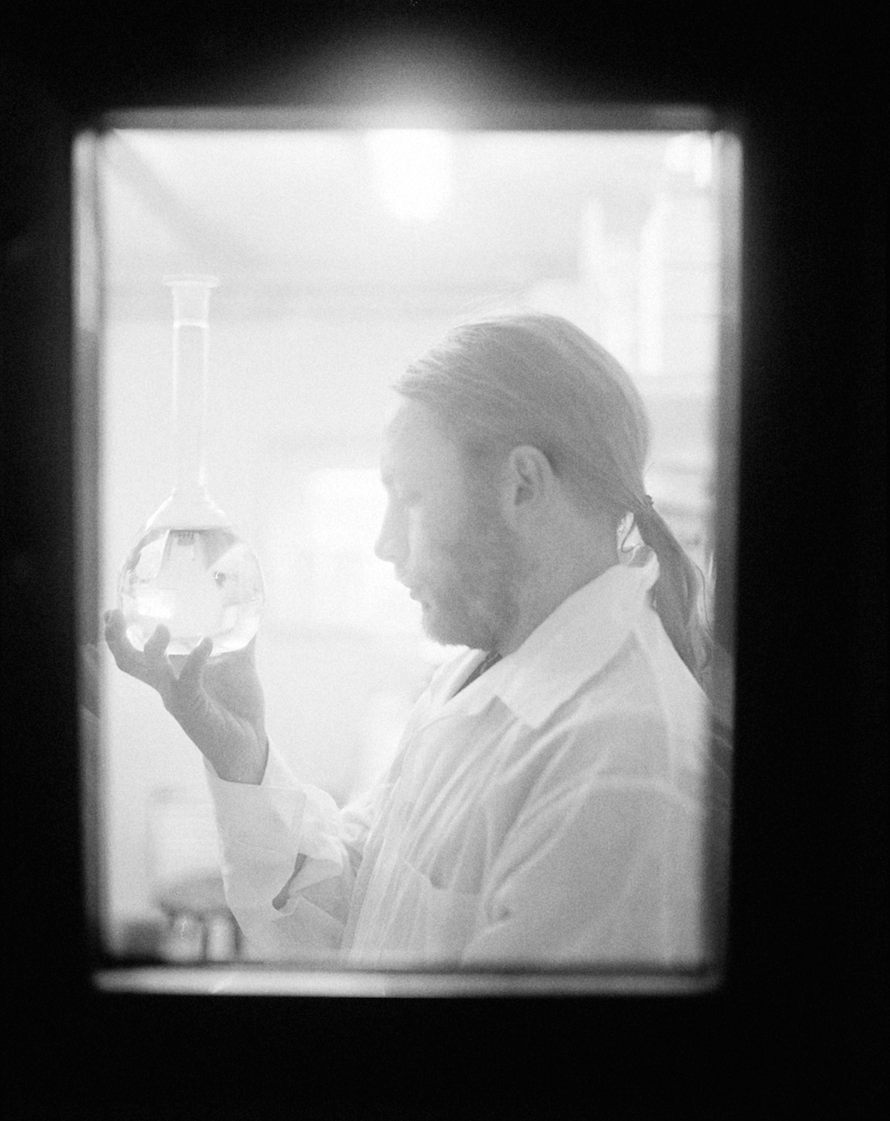

In January 2012, I was offered an opportunity to go to the North Pole, to the Polish Polar Station, Hornsund, on Spitsbergen. I learned about the very interesting research by Dr. Piotr Owczarek, who was going to Bear Island to collect rhizomes of the polar willow, Salix Polaris. It’s studied by dendrochronologists, who determine its age based on the number of growth rings. They also use microscopes to read its past from healed wounds in the figure of the wood. It was the first time I’d thought about the title for my photographic cycle. In a way, Salix Polaris became a symbol of my journey to the Pole. The group of people who travelled on the ship included climatologists, geologists, and glaciologists, going to Spitsbergen to continue the research on the Hans and the Werenskiold Glaciers. I also took photos of an IT specialist, who was there to check the devices in the station, geology students, and a gunsmith looking into the condition of the guns they used. Continue reading ↓

All images used with permission, copyright © the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

TMN: What about those “cold, open spaces”? Did you connect to the landscape as an artist?

AS: I could feel the total dependence on nature.

I used to be afraid of open spaces, but the emptiness turned out to be inspiring. No aggressive sounds, no intensive images or smells. So different from the city centre where I live. Suddenly, I realized I was feeling more confident on Spitsbergen than in the civilized world. Of course, I felt most confident when I was accompanied by a person armed against polar bears. (Laughs.)

TMN: You said in your project statement, “I believe science is just an excuse that allows [the scientists] to return here time and again.” Did the scientists tell you that? What are their lives like when they’re working?

AS: No, I have never heard the scientists actually say that, but I know Spitsbergen is an escape from everyday life for them. Their dreams are coming true. Interviewed by Herzog, Stefan Pashov says: “[The Pole] works almost like a natural selection for people that have this intention to jump off the margin of the map. And we all meet here, where all the lines of the map converge… [The people here] are the professional dreamers… Through them, cosmic dreams come into fruition, because the universe dreams through our dreams. There’s many different ways for the reality to bring itself forward, and dreaming is definitely one of those ways.”

I think Spitsbergen is a place where you are accepted and understood by other scientists. You self-realize. Life on the base is monotonous. Everybody works. Every day, if the weather allows, they go into the field. Every day, the climatologist collects samples of meteoric water. The geologist checks the Earth’s magnetism, reading data from the non-magnetic house. The seismic movements get analysed. It’s hard to make appointments to photograph anybody. When I was there, several research programs of various disciplines were underway. In the evenings people met in the wardroom to talk, drink, watch TV, listen to music.

TMN: What status do scientists have in Poland?

AS: That’s a bit tricky. On the one hand, Polish science could be described in negatives only: Polish academies leg behind in the world rankings; financing of science in Poland is very poor. On the other, however, in some disciplines, IT for instance, Polish academies educate very good professionals. I think that in the 25 years since the overthrow of Communism there have been many positive changes in Poland; as a country we’ve achieved a lot. In respect to science, however, we still face many serious challenges.

The scientists I met in the Polish Polar Station are very devoted to their jobs, even though the equipment they use is far from the best sometimes. They seem quite desperate, too.

Last year, the University of Silesia launched the Polar Research Centre, which is a pioneer in studies on the Arctic tidewater glaciers, and specializes in research on their climate and evolution. This year it has received the KNOW status for one of the most innovative Polish research centres.

Photography has somewhat turned to science of late. This year’s edition of Photomonth in Krakow, one of the biggest photo festivals in Poland, has Research for its theme. At the moment, I’m working with a therapist, Helena Zakliczyńska, to study the possibility of using photography in therapy of patients suffering from traumas.

TMN: As an artist, what was difficult about this project?

AS: At first, I was frustrated by the lack of understanding on the scientists’ side. My presence raised many questions, sometimes doubts even, initially. I realized our professions run parallel, but they never, or hardly ever, meet at all, and my book proves that. It also made me aware that our jobs are similar in being non-surreal. In both cases, there’s a particular work to do. We respected one another.

All the photos were taken in only a few days. Unfortunately, due to difficult weather conditions, my backpack with my Graflex camera and tripod couldn’t reach the station near the Werenskiold Glacier. This was a failure to me. Later, this failure, or obstacle, became one of the inspirations for making the book. It is a book about a struggle against nature and yourself.