Slow Photography

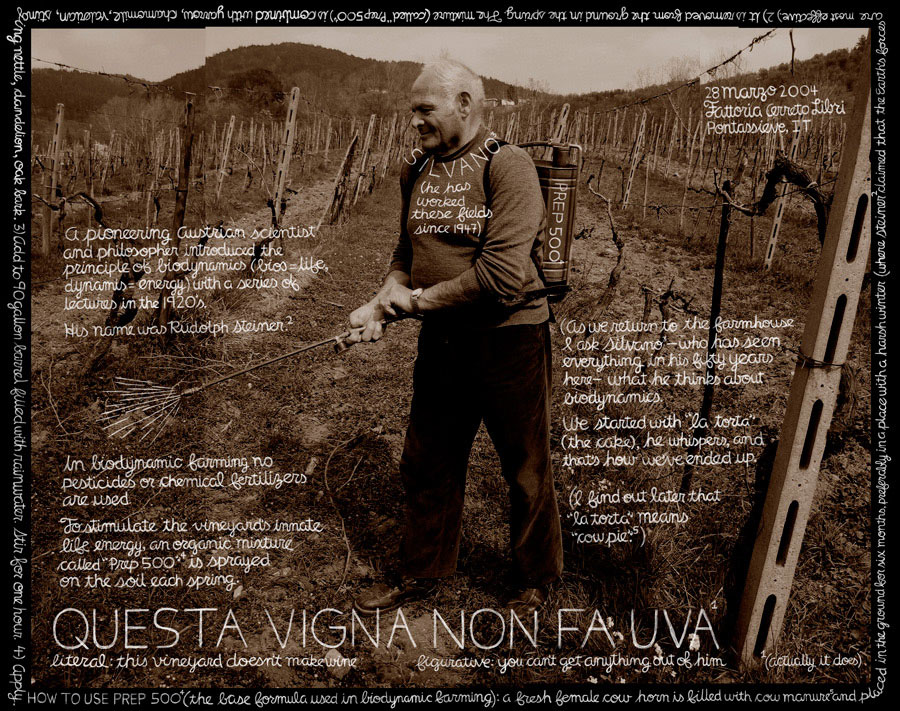

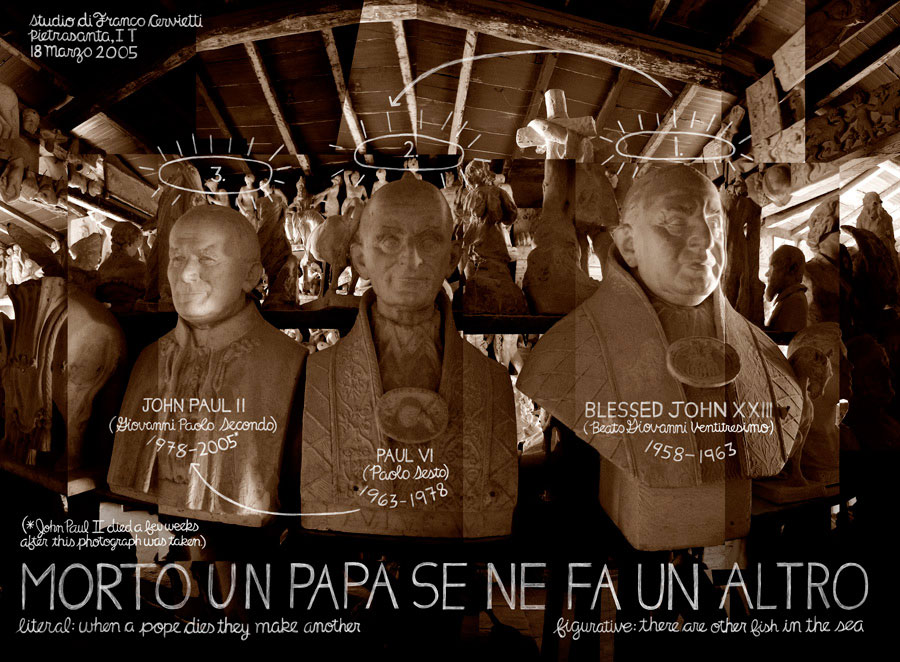

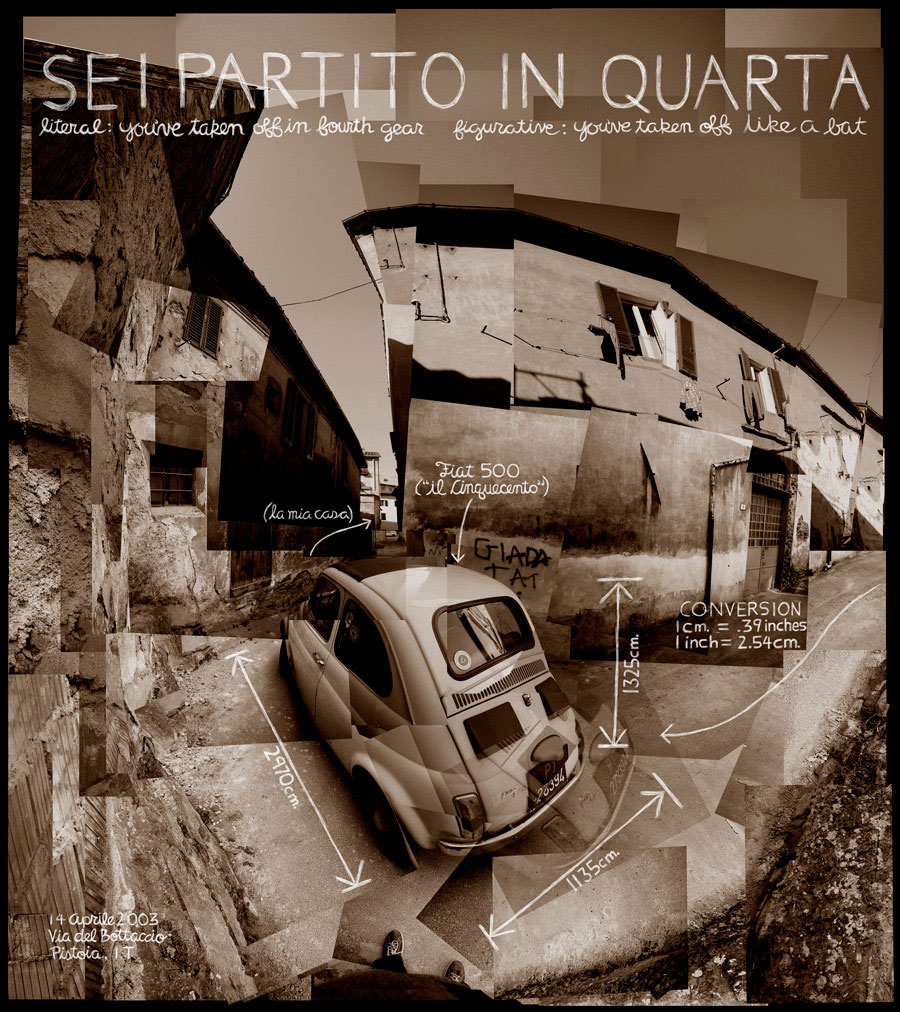

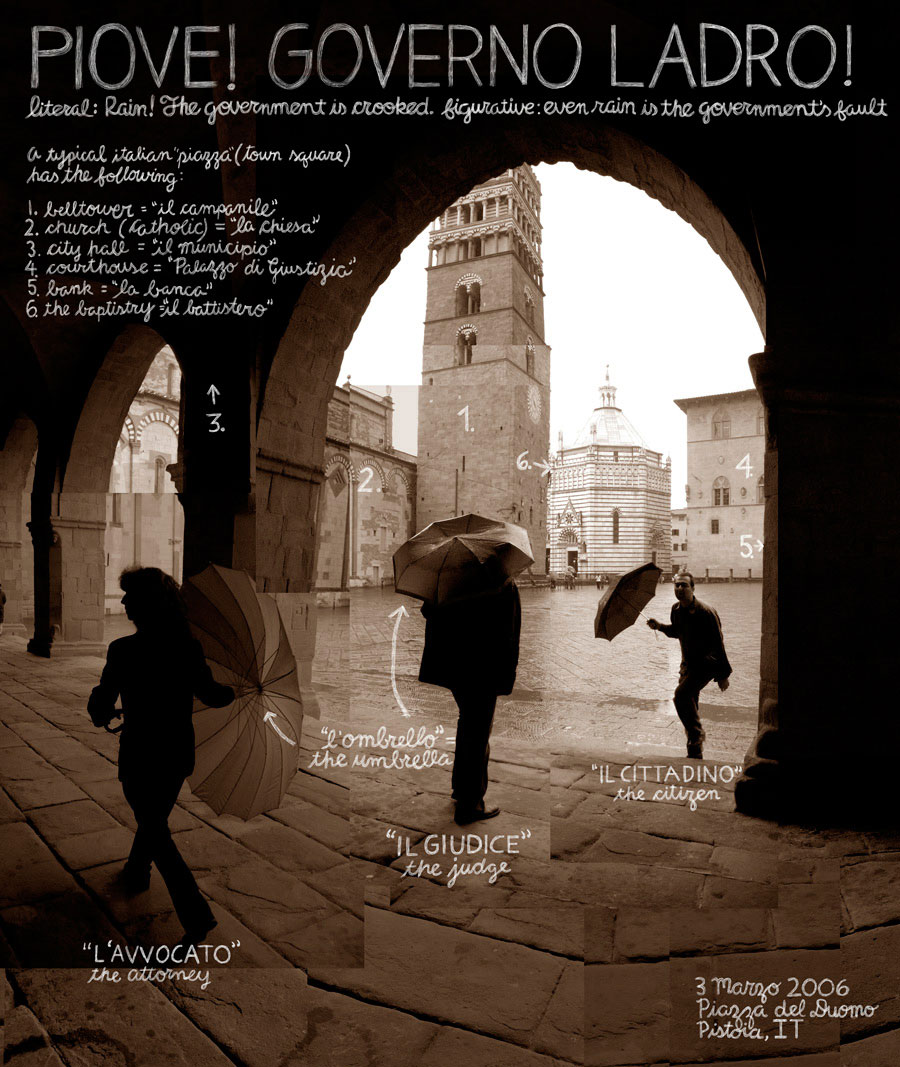

A series of portraits of a rural town in Italy where Douglas Gayeton lived, worked, cooked, fell in love, and took pictures—tons of pictures, many of which were then stitched together and inscribed with captions, names, anecdotes, and recipes to tell his story of assimilation.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

How did the process develop of overlapping your images and writing?

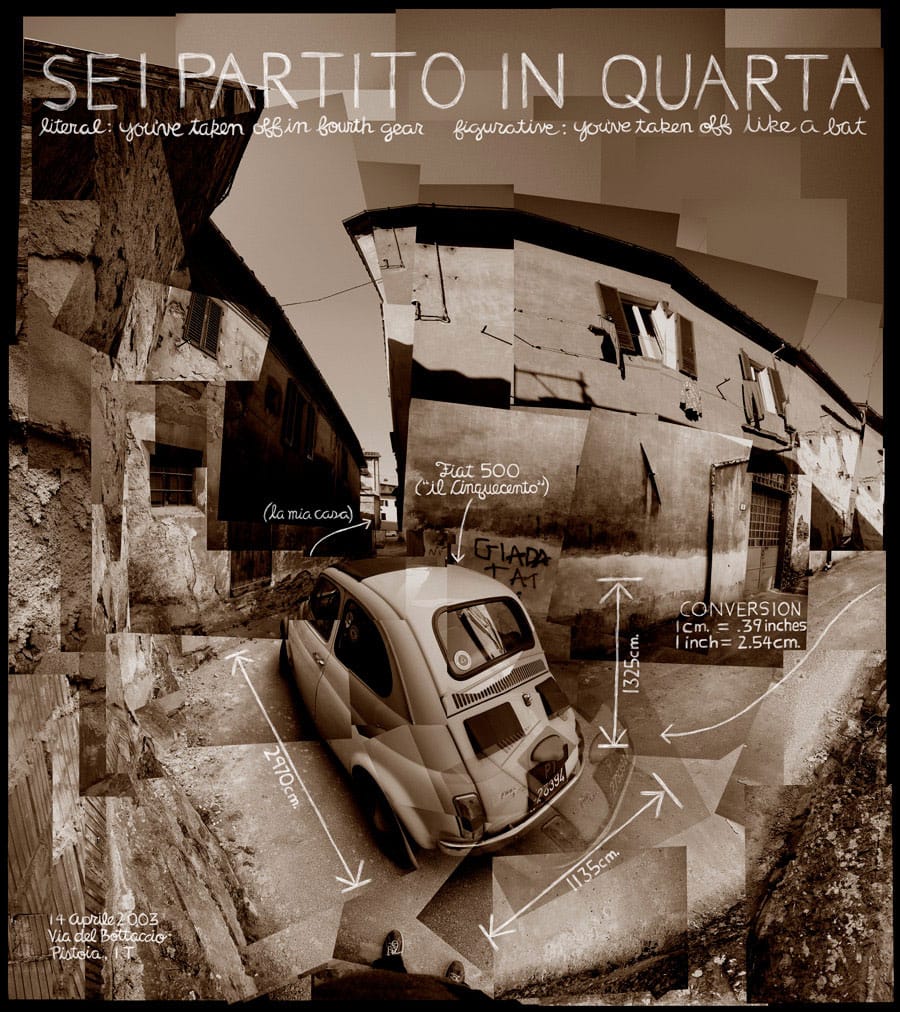

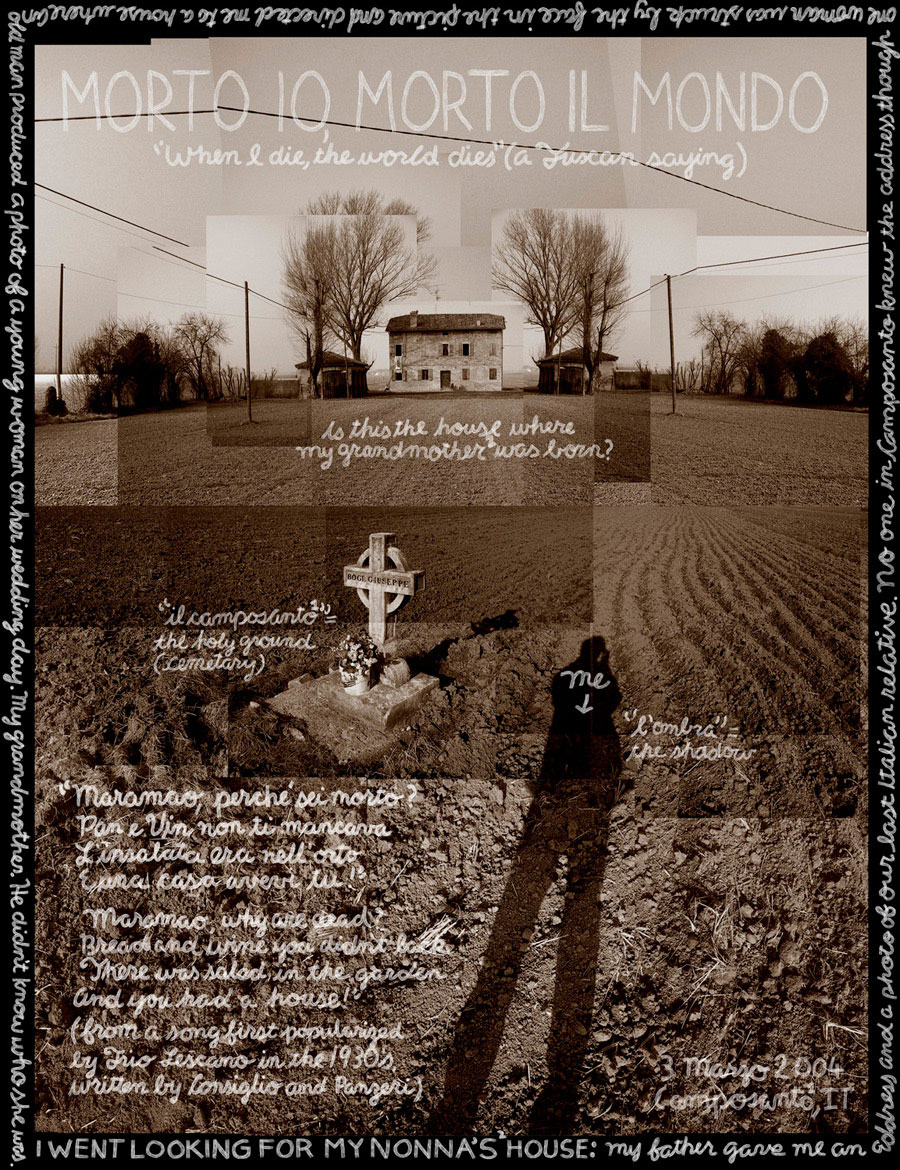

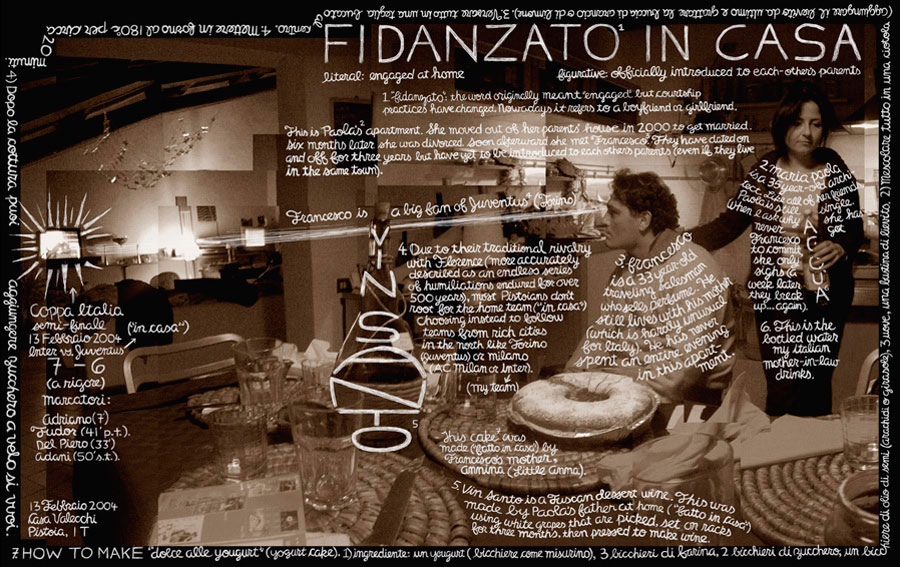

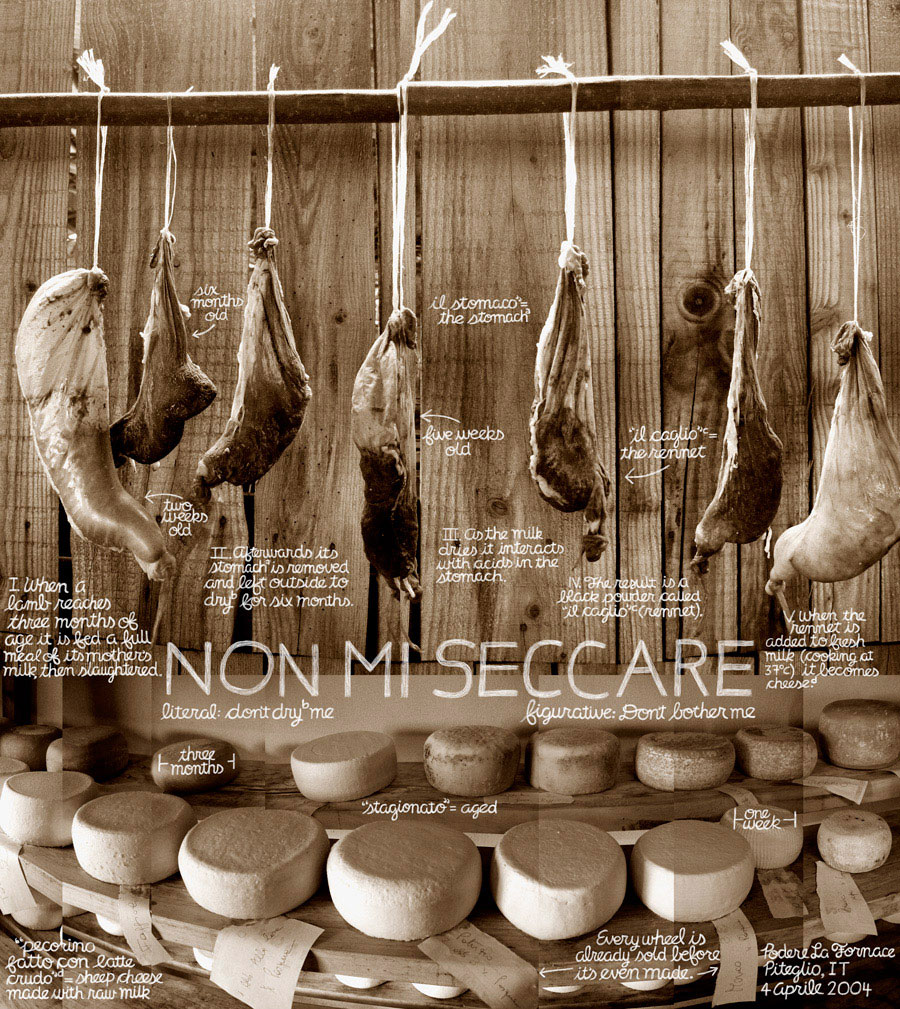

The decision to write on the images was a conscious choice. When I first immersed myself in the life of Pistoia, a Tuscan town in Pistoia, I had so many questions, and when I first began taking photographs there I’d often look at them and wonder, who are these people? How are they connected to each other? What are they doing? What are those strange objects around them? It struck me as something very natural to actually write these notes directly on the images. The photographs became a graphical chart, a roadmap that helped me decode the life of this strange new town I’d found myself living in. Continue reading ↓

Pornography for the Heat-reading set, Slow: Life in a Tuscan Town (Welcome Books) is the Slow Food movement brought to art (it even has its own dinner tour). All images © copyright the artist, courtesy of Welcome Books, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

Does the “slow” approach apply to your approach as a photographer?

Well, each photograph in the book is actually not one but at times hundreds of individual photographs combined together. The process of photographing can take hours. Then the writing on each image takes weeks. The text is a collaboration between me and my subjects. We work on them together, which also takes time—so yes, you could say I have a “slow” approach to photography, both because I forge a relationship with my subject and because these aren’t quick snapshots taken from a moving car. They’re carefully plotted and intimate.

Is the “slow” way of life something actually attainable by most people, or is it a fantasy for urban greenmarket-goers?

You don’t have to live in a small rural town to have a slow life. Even if you are up at six each morning, grabbing a coffee and a muffin which you eat while commuting an hour from your suburban tract-home to work in an air-conditioned glass tower in the heart of faceless urban center—you can still lead a slower life. It all begins by making a few very specific choices. By being mindful of what you eat, of where it comes from. Of who grew it and who sells it. Make yourself part of that local food chain, even if you’re just the consumer frequenting your local farmers’ market. Reconnecting to the land will lead to a number of unexpected consequences. The more you tie yourself to a local lifestyle, the more you open yourself up to new opportunities, alternative ways of thinking (even new forms of work) that ultimately change your world view. And it all starts with what you serve on your table.

What do you remember from the last time you ate at McDonald’s?

I felt sick. Poisoned. At the same time, I try not to judge people who eat there. The food is cheap, and it gives the illusion of completeness. The decision to eat fast food is justified by many as a convenience, but I wonder if it isn’t more like laziness. Part of the blame must be shouldered by how we educate our young. In Europe, children get both a nutritional and gastronomic education. This is recognized as being part of the cultural patrimony passed from one generation to the next. As a young nation we never had this cultural knowledge to pass along to our young, so we need to think of some other way to provide kids with this education. Alice Waters and the Slow Food movement have made this a top priority in the U.S.

In the book, you point out that you’ve come full circle: you live in California again, where you were prior to Italy, but now you’re making an artisanal product and living off the land. If you hadn’t met your wife, could you have envisioned staying in Pistoia?

If I hadn’t met my wife and moved to Sonoma I would probably be making olive oil in Pistoia. I would probably still be gathering images for this book!