Surreal Eden

Margaret Hooks tells the story of Edward James: wealthy British surrealist-art benefactor turned rural Mexican architect, demi-god and dreamer.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

Give us a brief idea of Edward James’s background. How did a wealthy British boy become so close to Salvador Dali, and then wind up building this surreal city in the jungle?

Edward James was born into an enormously wealthy aristocratic family encased in the constraints of England’s Edwardian mores. His life was propelled by the imagination, and as a child he escaped the strictures that surrounded him by imagining and writing about a fantastical place called “Seclusia.” Continue reading ↓

All photos are copyright and appear courtesy of Princeton Architectural Press, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

When he inherited the family fortune, he lavished it on artistic ventures, searching out artists whose work inspired him. He became the leading patron of several renowned artists, such as Salvador Dali, Rene Magritte, and Leonora Carrington. He had a very hands-on approach to the work of the artists he patronized. He sponsored and helped design Dali’s Lobster Telephone and Mae West’s Lips Sofa, and was the subject of some of Magritte’s best-known works. He knew he’d overstepped the mark, however, when Leonora Carrington threw him out of her home after discovering him making some furtive additions to a canvas she was working on, apparently painting testicles on one of her surreal creatures.

In fact, he wanted desperately to be an artist in his own right, and to be taken seriously as a poet, but literary success confounded him. When he was savaged in a review by Stephen Spender, he turned his back on England and its bickering, backstabbing literary milieu and embarked on a odyssey that took him to America and eventually to Mexico, where he finally found that magical world he’d dreamed of as a child, the perfect setting for the creation of his secret walled city.

What was it about Mexico that made James feel so at home?

It was initially a bizarre experience when the friend he was traveling with was swimming in a river, and when he walked out of the water he was covered in a cloak of quivering butterflies. To Edward James this was a quintessential surreal experience and an omen to that it was the place he’d been searching for. The place was in fact on the outskirts of Xilitla [a town in the central Mexican state of San Luis Potosí—ed.], where he eventually created Las Pozas. Basically he felt at home at home in Xilitla’s “magical surrealism” and it was only there, in this other world, far from the madding critics, that he was able to become what he’d always wanted to be—an artist in his own right.

What was James’s purpose, his vision in creating Las Pozas?

Actually, Las Pozas has no purpose at all. Sometimes Edward James came up with temporary purposes but they never came to fruition. He described his project initially as a sanctuary created for his “ideas and illusions” but his vision was an unfolding, ever changing vision, which is how Las Pozas is experienced by those who visit it; people come away with their own interpretation, with their own private Las Pozas.

Is it true he was wrapped in toilet paper when he stumbled onto the site?

Yes, when he arrived in Xilitla for the first time, he had wrapped himself in toilet paper to keep warm. He was an eccentric and to him the solution was a practical one. He only became self-conscious about it when he saw how the inhabitants of Xilitla reacted to seeing this very bizarre-looking figure in their midst.

What sort of relationship did James have with his workers?

He had a complicated relationship with them, but all of the workers I’ve spoken with describe working on Las Pozas with him in almost mystical terms. I think having worked on something that is now so appreciated has given them great pride.

Did James consider himself a Surrealist?

No, not a Surrealist with a capital “S.” In fact, he disliked all the manifestos and creeds that enveloped the movement. It was how he lived his life that was surreal. However, he was obviously deeply involved with the surrealists, and Las Pozas is, in effect, a surrealist work, sometimes self-consciously so in the names that were given to structures, as in “Homage to Max Ernst.”

What is Las Pozas like now? Can tourists visit and explore? Can they spend the night?

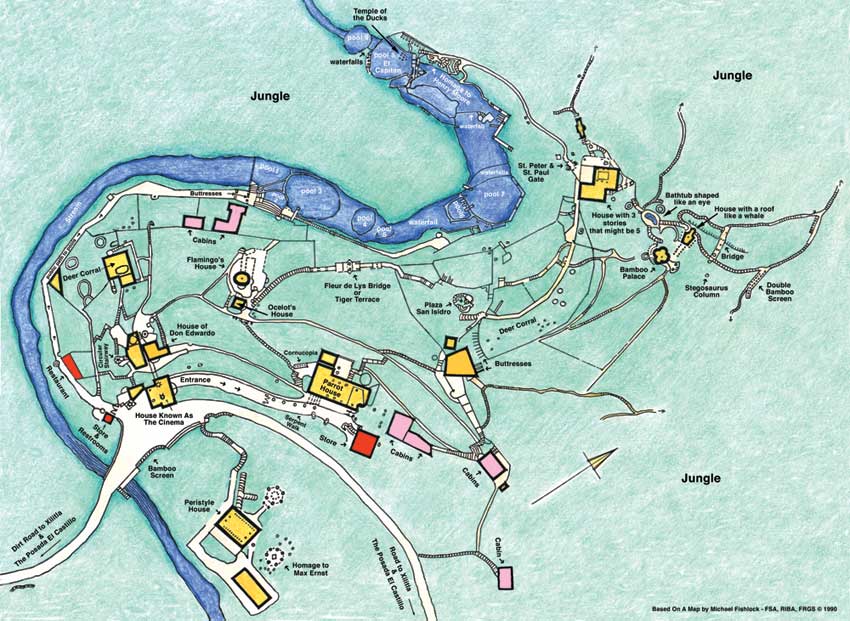

Las Pozas becomes more splendid with the passing of time, as it is encroached on by the jungle. It is an awe-inspiring experience, and on each visit you find new elements. It penetrates all the senses: there is the backbeat of the waterfall, the sounds of birds and other creatures, the luscious perfumes of orchids, and the extraordinarily colored, soaring structures.

It is possible to stay in some simple cottages built near the entrance to the site, and then there is also the house where Edward James lived in Xilitla, which is now a small hotel.

What are you working on next?

I have a book on the recent work of the Catalan photographer Manel Armengol coming out next month and I’m currently working on a book on art, architecture, and design in Miami.