The Art of the American Snapshot

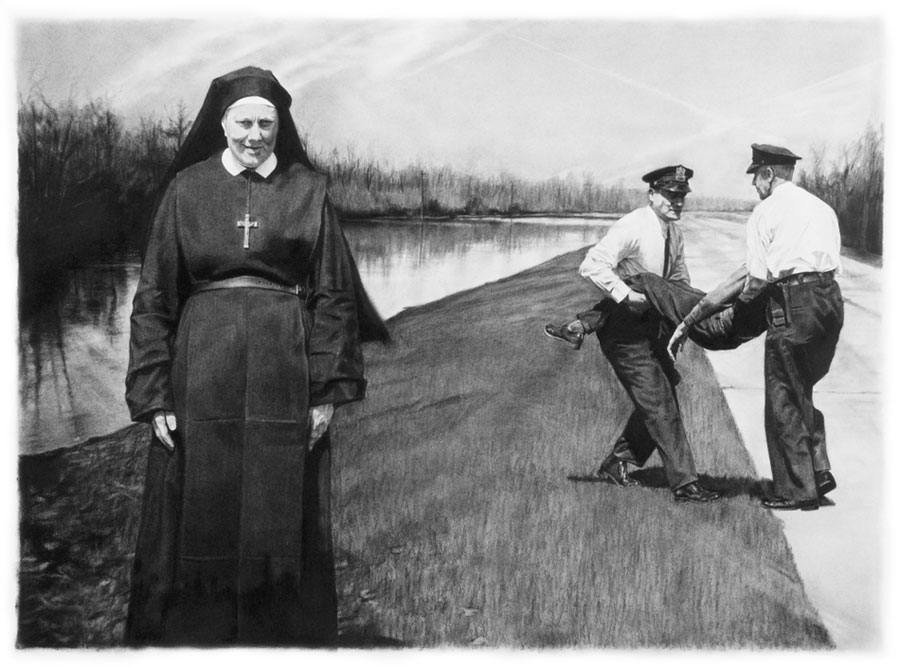

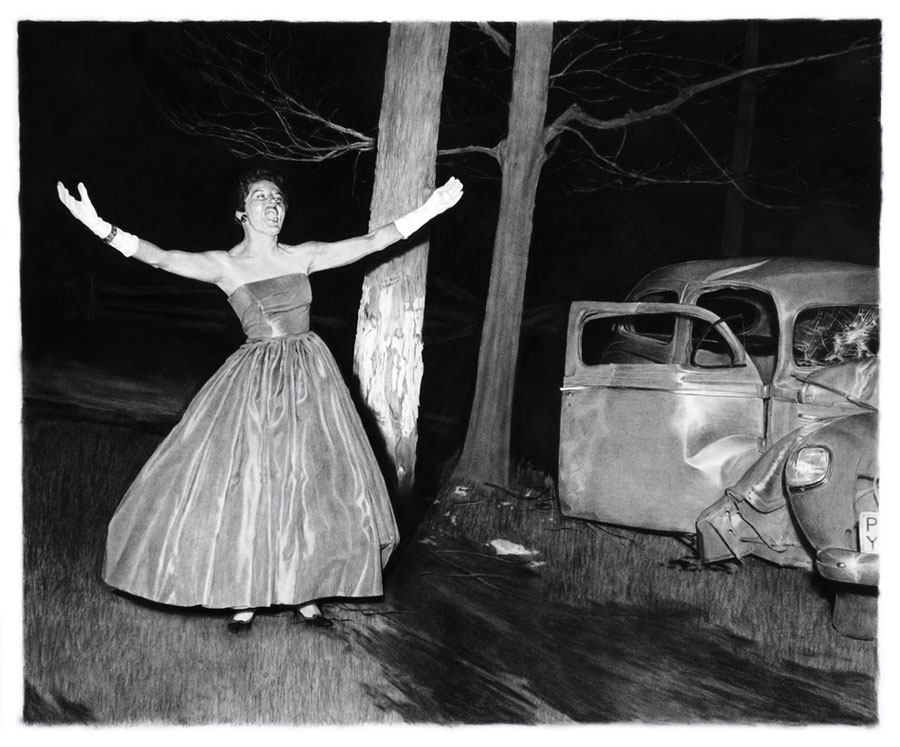

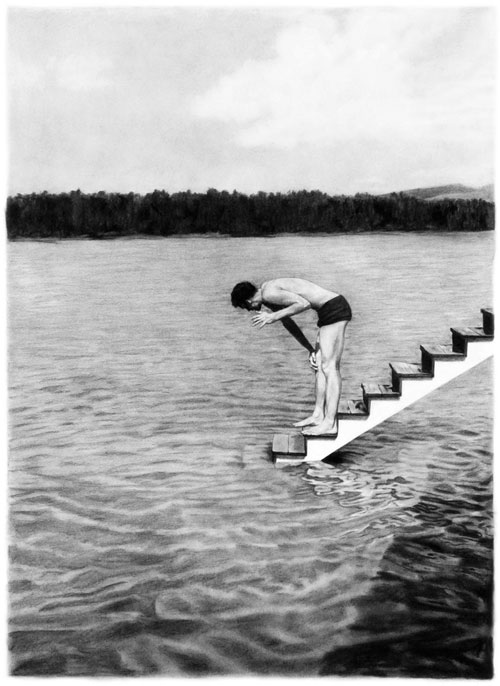

Scott Hunt’s drawings take inspiration from mysterious, uncomfortable, hilarious, and sad moments in amateur photography and give them new life. His work makes that old photo of your grandpa in stockings at the office Christmas party iconic.

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

What do you find inspiring about other people’s photographs?

I love the aesthetic of snapshots, especially ones from the ’40s and ’50s, due to their wide range of tonal values. And I respond to what I refer to as the “felicitous mistakes” that amateur photographers make: the skewed horizon lines, halation, odd croppings, and focus on unintended subjects.

But other people’s snapshots are also little mysteries; they have a history that’s lost and that can’t be accessed. That severed link to the past fascinates me and gives me a vague sense of anxiety that compels me to create my own stories about who these people were, what brought them to this particular moment in time, and what preceded and followed the snap of the shutter. Continue reading ↓

All images used with permission, © copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

What do you look for in a picture? Are there particular details or characteristics that make you want to draw a certain photo?

I think that what I look for mostly is the iconic. The less specific my references are, the more ambiguous the meaning of the work can be. I’m always hoping for a wide range of interpretation for my drawings. I seldom recreate a photo directly, though. I don’t see much sense in that. What I generally do is identify elements in a photo that attract me—a figure, a house, an interior space—and then I isolate them, pluck them out of their original setting, and mix them with elements from other photographs I’ve found. Then I print out the reconfigured tableau and draw from that.

Where do these images come from?

Wow, that’s an enormously difficult question. I’m not sure that I know exactly where my images come from and I probably prefer it that way. My work requires a certain amount of unconsciousness to make the wheels turn. But I think that, like most people, the lens that I see the world through was ground to its unique focus by the experiences of childhood. I grew up in a somewhat idyllic suburban New York neighborhood that was very tight-knit. I led a pretty sheltered life until everything was turned suddenly on its head when I was 10 by a serious health problem. I think that the trauma of that experience informed my perception of what life is. It made me embrace duality and gave me an affinity for the dark, messy, in-between places in our lives. I think that comes through in my work.

Do you have narratives in mind when you’re working on an image?

A lot of my work is narrative and then there’s a fair amount of it that’s allegorical. But when I’m working in a narrative vein, I usually let the story suggest itself to me, much in the way that many fiction writers do. I sit with the photographic elements I’m working with and allow them to push my imagination around until I get a whiff of where the story is going. Then I build around that. It’s not really a very linear process and I have to say that I sometimes get finished and find that the narrative I thought I was weaving is completely different from what’s ended up on the page. That’s why the unconsciousness I mentioned earlier is important… You just have to let your subconscious do the yeoman’s work. It’s not that I’m not thinking or making choices. It’s just that if I’m working on a purely conscious level, the work feels more forced and almost always less interesting.

How did you end up illustrating a children’s book?

I was trained as an illustrator and that’s how I made my living for many years. In the late ’90s I began to feel unhappy with the kind of work I was getting and restless to be more independent. So, prompted by that discontent, I had an idea for a book that would explore the elasticity of interpreting figurative art. I produced a series of nine charcoal drawings—thematically unrelated but stylistically consistent—that had ambiguous and unresolved narratives. Each drawing was then given to a different pair of writers. Working individually, each writer was asked to create a short story or poem inspired by the art. Then they were asked to contribute a short piece on the unique challenges of using another art form as the catalyst for their own work. The drawings and all of the writing were then published together as a short story collection called Twice Told (Dutton). I had originally intended it to be a book for adults but it works as a young adult book incredibly well; it’s a great tool for teaching about the creative process, artistic collaboration, and the malleable nature of interpretations of visual art.

How is the “That Sticky Candy” series different from your previous work?

That was a series that was defined by an issue. I had done issue-oriented work before—living with HIV, ecologic degradation, domestic violence—but they’d been isolated drawings within a larger context. “Sticky Candy” grew out of my questioning what gay identity is, both as perceived by the straight community and by gays themselves.

It began with one of my many trips to a flea market to hunt for snapshots. Some of the vendors have their photos separated into categories as do the vendors on eBay and I began to notice that the binders that were labeled “Gay Interest” primarily contained pictures of pornography, sailors hugging or in drag, soldiers defecating (I kid you not), body builders, and anyone with their shirt off, preferably in a tight bathing suit. The files almost never included women and, if they did, invariably it was women in drag.

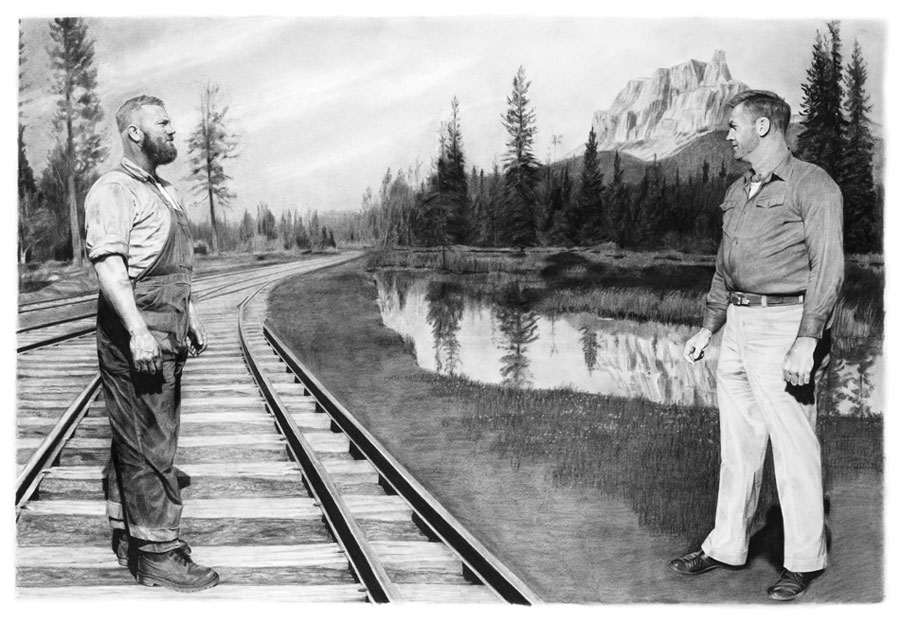

I began to think about this narrow interpretation of what constitutes gay interest and I wondered who was fueling this perception and how much of it was true. I started to play around with imagery that is conventionally considered homoerotic and began working those elements into drawings that had much deeper and complex meanings. Would the viewer be able to look past the homoerotic nature of the subjects and see anything deeper or would the work be dismissed as merely “gay art?” That jettisoned into my thinking about the loss of heterosexual male physical intimacy due to homophobia, what constitutes a gay context (does the presence of two men in a drawing necessarily make it gay-themed?), the hyper-sexualizing of gay male culture, and a whole host of other questions.

What is interesting to you personally about photos of men in drag?

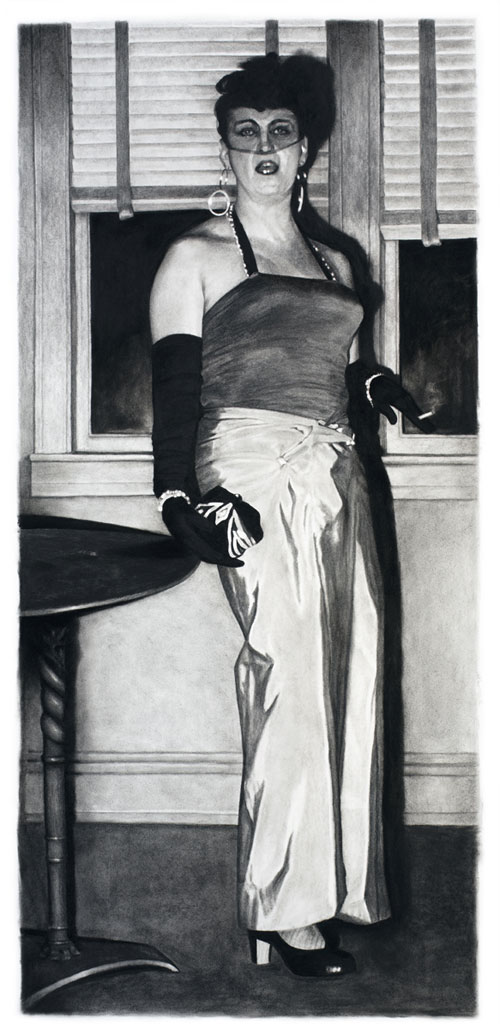

Well, I don’t think I have any particular interest in photos of men in drag. But, as I mentioned earlier, I’m drawn to dualities so drag is a great subject matter for me. For “That Sticky Candy” I wanted to create a formal portrait, in the vein of Sargent’s “Madame X,” but using a drag queen as my subject. In my experience, men who dress in drag have an obvious love of kitsch but there is no doubting their devotion to everything female or their commitment to the characters they inhabit. It was important to me to preserve drag’s camp qualities while also treating my subject with respect and a bit of glorification. I wanted the viewer to see the humor but also to take my “Madame” as seriously as the subjects painted by Sargent, Valazquez, or Manet.

How is it that an image of two burly men in work clothes staring at each other is seen as a “gay” image?

You’re referring to my drawing “Nature vs. Industry” which depicts two men in profile facing each other in a wilderness landscape. The question you raise is one that I was hoping would be asked about the work, but you’re the first to do it. That piece began simply as a drawing of two men cruising each other. I then subverted my original intent by placing the figures in a 19th-century landscape and then creating separation between them: psychic, physical, social, and situational. So the initial focus of the piece became obscured and this other dynamic of opposition and comparison took over. The interesting question for me is: If one saw that piece in isolation, out of the context of a show with gay themes, would the average viewer simply see it as a drawing of two men or, by virtue of having two male figures in it, would they see it as a drawing with gay content?