The Frightening Beauty of Bunkers

Approximately 1,500 bunkers were built during World War II along the French shores to forestall an Allied landing—“the Atlantic Wall.” Decommissioned after the Allied invasion of Normandy, this elaborate defense system now lies abandoned.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

At the age of 25, Paul Virilio stumbled upon the relics of “the Atlantic Wall” with his camera and began a study that would continue for 30 years. His 1975 book, Bunker Archeology, has recently been translated into English and reprinted by Princeton Architectural Press: an inquiry of war and its structures and a personal memoir of exploration, merging technical analysis with philosophical questioning.

The essay below is excerpted from Virilio’s preface for the book. Continue reading ↓

Book text and all images © copyright the author, courtesy of Princeton Architectural Press, all rights reserved.

Preface

During my youth, work on the European littoral forbade access to it; they were building a wall and I would not discover the ocean, in the Loire estuary, before the summer of ’45.

The discovery of the sea is a precious experience that bears thought. Seeing the oceanic horizon is indeed anything but a secondary experience; it is in fact an event in consciousness of underestimated consequences.

I have forgotten none of the sequences of this finding in the course of a summer when recovering peace and access to the beach were one and the same event. With the barriers removed, you were henceforth free to explore the liquid continent; the occupants had returned to their native hinterland, leaving behind, along with the work site, their tools and arms. The waterfront villas were empty, everything within the casemates’ firing range had been blown up, the beaches were mined, and the artificers were busy here and there rendering access to the sea.

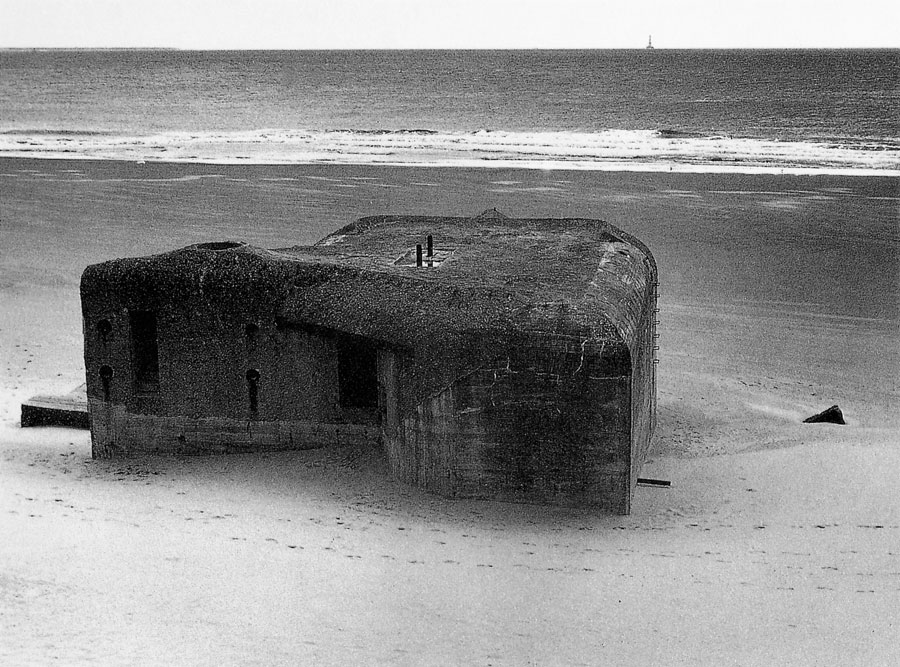

The clearest feeling was still one of absence: the immense beach of La Baule was deserted, there were less than a dozen of us on the loop of blond sand, not a vehicle was to be seen on the streets; this had been a frontier that an army had just abandoned, and the meaning of this oceanic immensity was intertwined with this aspect of the deserted battlefield.

But let us get back to the sequences of my vision. The rail car I was on, and in which I had been imagining the sea, was moving slowly through the Brière plains. The weather was superb and the sky over the low ground was starting, minute by minute, to shine. This well-known brilliance of the atmosphere approaching the great reflector was totally new; the transparency I was so sensitive to was greater as the ocean got closer, up to that precise moment when a line as even as a brushstroke crossed the horizon: an almost glaucous gray-green line, but one that was extending out to the limits of the horizon. Its color was disappointing, compared to the sky’s luminescence, but the expanse of the oceanic horizon was truly surprising: could such a vast space be void of the slightest clutter? Here was the real surprise: in length, breadth, and depth the oceanic landscape had been wiped clean. Even the sky was divided up by clouds, but the sea seemed empty in contrast. From such a distance there was no way of determining anything like foam movement. My loss of bearings was proof that I had entered a new element; the sea had become a desert, and the August heat made that all the more evident—this was a white-hot space in which sun and ocean had become a magnifying glass scorching away every relief and contrast. Trees, pines, etched-out dark spots; the square in front of the station was at once white and void—that particular emptiness you feel in recently abandoned places. It was high noon, and luminous verticality and liquid horizontality composed a surprising climate. Advancing in the midst of houses with gaping windows, I was anxious to be done with the obstacles between myself and the Atlantic horizon; in fact I was anxious to set foot on my first beach. As I approached Ocean Boulevard, the water level began to rise between the pines and the villas; the ocean was getting larger, taking up more and more space in my angle of vision. Finally, while crossing the avenue parallel to the shore, the earth line seemed to have plunged into the undertow, leaving everything smooth, no waves and little noise. Yet another element was here before me: the hydrosphere.

When calling to mind the reasons that made the bunkers so appealing to me almost twenty years ago, I see it clearly now as a case of intuition and also as a convergence between the reality of the structure and the fact of its implantation alongside the ocean: a convergence between my awareness of spatial phenomena—the strong pull of the shores—and their being the locus of the works of the “Atlantic Wall” (Atlantikwall) facing the open sea, facing out into the void.

It all started—it was a discovery in the archeological sense of the term—along the beach south of Saint-Guénolé during the summer of 1958. I was leaning against a solid mass of concrete, which I had previously used as a cabana; all the usual seaside games had become a total bore; I was vacant in the middle of my vacation and my gaze extended out over the horizon of the ocean, over the perspective of sand between the rocky massifs of Saint-Guénolé and the sea wall in the port of Guilvinec to the south. There were not many people around, and scanning the horizon like that, with nothing interrupting my gaze, brought me full round to my own vantage point, to the heat and to this massive lean-to buttressing my body: this solid inclined mass of concrete, this worthless object, which up to then had managed to martial my interest only as a vestige of the Second World War, only as an illustration for a story, the story of total war.

So I turned around for an instant to look at what my field of vision onto the sea had not offered up: the heavy gray mass where traces of planks lined up along the inclined ramp like a tiny staircase. I got up and decided to have a look around this fortification as if I had seen it for the first time, with its embrasure flush with the sand, behind the protective screen, looking out onto the Breton port, aiming today at inoffensive bathers, its rear defense with a staggered entrance and its dark interior in the blinding light of the gun’s opening toward the sea.

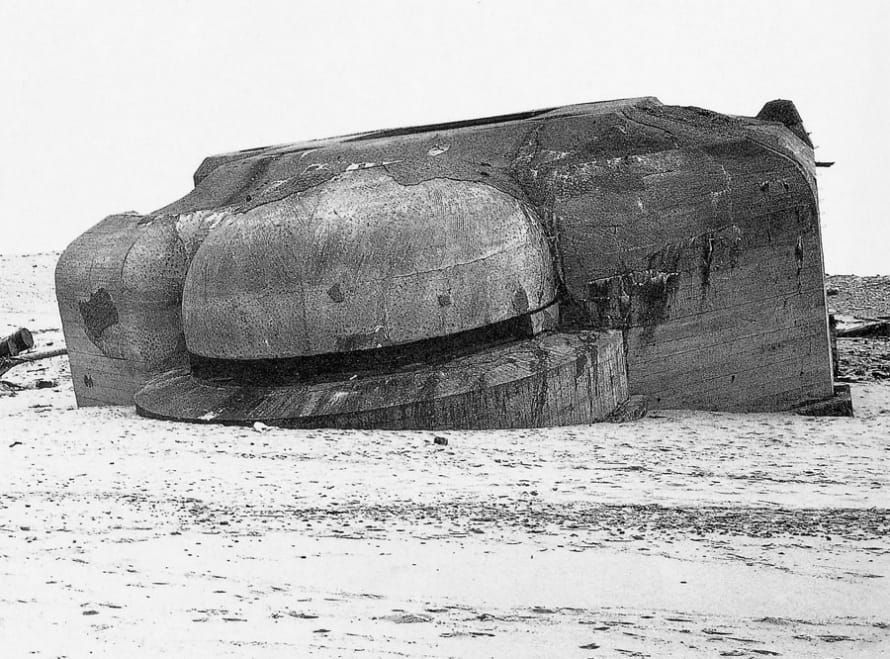

I was most impressed by a feeling, internal and external, of being immediately crushed. The battered walls sunk into the ground gave this small blockhouse a solid base; a dune had invaded the interior space, and the thick layer of sand over the wooden floor made the place ever narrower. Some clothes and bicycles had been hidden here; the object no longer made the same sense, though there was still protection here.

A complete series of cultural memories came to mind: the Egyptian mastabas, the Etruscan tombs, the Aztec structures…as if this piece of artillery fortification could be identified as a funeral ceremony, as if the Todt Organization could manage only the organization of a religious space…

This was nothing but a broad outline, but from then on my curiosity would be quickened; my vacation had just come to an end, and I could guess that these littoral boundary stones were to teach me much about the era, and much about myself.

On that day I decided to inspect the Breton coasts, most often on foot along the high-tide line, further and further; by car as well, in order to examine distant promontories, north toward Audierne and Brest, southward to Concarneau.

My objective was solely archeological. I would hunt these gray forms until they would transmit to me a part of their mystery, a part of the secret a few phrases could sum up: why would these extraordinary constructions, compared to the seaside villas, not be perceived or even recognized? Why this analogy between the funeral archetype and military architecture? Why this insane situation looking out over the ocean? This waiting before the infinite oceanic expanse? Until this era, fortifications had always been oriented toward a specific, staked-out objective: the defense of a passageway, a pass, steps, valleys, or ports, as in the case of the La Rochelle towers; it had always been a question of “guarding,” as easy to understand as the caretaker’s role. Whereas here, walking daily along kilometer after kilometer of beach, I would happen upon these concrete markers at the summit of dunes, cliffs, across beaches, open, transparent, with the sky playing between the embrasure and the entrance, as if each casemate were an empty ark or a little temple minus the cult. It was indeed the whole littoral that had been organized around these successive bearings. You could walk day after day along the seaside and never once lose sight of these concrete altars built to face the void of the oceanic horizon.

The immensity of this project is what defies common sense; total war was revealed here in its mythic dimension. The course I had begun to run, over the banks of Festung Europa (Fortress Europe), was going to introduce me into the reality of Occidental geometry and the function of equipment on sites, continents, and the world.

Everything was suddenly vast. The continental threshold had become a boulevard—the linearity of my exploration; sun and sand were now personal territory that I was beginning to like more and more. This continuous band of dunes and pebbles and the sharp crest of the cliffs along the coast fit into a nameless country where the three interchanges were glimpsed: the oceanic and aerial space along with the end of emerged land. The only bearings I had for this trip from the south to the north of Europe were these stelae whose meaning was still unsure. A long history was curled up here. These concrete blocks were in fact the final throw-offs of the history of frontiers, from the Roman limes to the Great Wall of China; the bunkers, as ultimate military surface architecture, had shipwrecked at lands’ limits, at the precise moment of the sky’s arrival in war; they marked off the horizontal littoral, the continental limit. History had changed course one final time before jumping into the immensity of aerial space.

My activities often led me into teeming ports, and what most surprised and intrigued me there was finding once again in the middle of courtyards and gardens my concrete shelters; their blind, low mass and rounded profile were out of tune with the urban environment. As I concentrated on these forms in the middle of apartment buildings, in courtyards, and in public squares, I felt as though a subterranean civilization had sprung up from the ground. This architecture’s modernness was countered by its abandoned, decrepit appearance. These objects had been left behind, and were colorless; their gray cement relief was silent witness to a warlike climate. Like in certain works of fiction—a spacecraft parked in the middle of an avenue announcing the war of the worlds, the confrontation with inhuman species—these solid masses in the hollows of urban spaces, next to the local schoolhouse or bar, shed new light on what “contemporary” has come to mean.

Why continue to be surprised at Le Corbusier’s forms of modern architecture? Why speak of “brutalism”? And, above all, why this ordinary habitat, so very ordinary over so many years?

These heavy gray masses with sad angles and no openings—excepting the air inlets and several staggered entrances—brought to light much better than many manifestos the urban and architectural redundancies of this postwar period that had just reconstructed to a tee the destroyed cities. The antiaircraft blockhouses pointed out another lifestyle, a rupture in the apprehension of the real. The blue sky had once been heavy with the menace of rumbling bombers, spangled too with the deafening explosions of artillery fire. This immediate comparison between the urban habitat and the shelter, between the ordinary apartment building and the abandoned bunkers in the hearts of the ports through which I was traveling, was as strong as a confrontation, a collage of two dissimilar realities. The antiaircraft shelters spoke to me of men’s anguish and the dwellings of the normative systems that constantly reproduce the city, the cities, the urbanistic.

The blockhouses were anthropomorphic; their figures recalled those of bodies. The residential units were but arbitrary repetitions of a model—a single, identical, orthogonal, parallelepipedal model. The casemate, so easily hidden in the hollow of the coastal countryside, was scandalous here, and its modernness was due less to the originality of its silhouette than to the extreme triviality of the surrounding architectural forms. The curved profile brought with it into the harbor’s quarters a trace of the curves of dunes and nearby hills, and there, in this naturalness, was the scandal of the bunker.

We identified these constructions with their German occupants, as if they had in their retreat forgotten their helmets, badges, here and there along our shores….Several bunkers still sported hostile graffiti, their concrete flanks covered with insults against “Krauts” and swastikas, and the interest I was showing in measuring and taking pictures of them sometimes had me bearing the hostile brunt…

Many of them had been destroyed by this iconoclastic vengeance when the territory had been liberated; their basements had been filled with munitions gathered up along the way and the explosion of the solid concrete mass had overjoyed the countryside’s inhabitants, as in a summary execution. Many riverains told me that these concrete landmarks frightened them and called back too many bad memories, many fantasies too, because the reality of the German occupation was elsewhere, most often in banal administrative lodgings for the Gestapo; but the blockhouses were the symbols of soldiery.

Once again there is this sign: these buildings brought upon themselves the hatred of passersby, as they had only yesterday concentrated the fear of death of their endangered users. For those who at that time saw them, they were not yet archeological; I believe I was alone in seeing something else springing up, a new meaning for these landmarks aligned along the European littoral.

I remember a comeback I had devised to answer the curiosity of those wishing to know the reasons for my studying the Atlantic Wall. I would ask if people still had the opportunity to study other cultures, including the culture of adversaries—if there were any Jewish Egyptologists. The answer was invariably, “Yes, but it is a question of time…time must pass before we are able to consider anew these military monuments.”

In the meantime, the bunkers were filled with litter or were shelter for less ideologically inclined vagabonds; the concrete walls were covered with ads and posters, you could see Zavatta the Clown on the iron doors and Yvette Horner smiling in the embrasure.

My vision appeared to be countered by that of my contemporaries, and the semireligious character of the beach altars, left for children’s play, was counteracted by resentment. What was the nature of this criticism? We violently rejected the bunkers as symbols rather than logically, with patience: as so many people said, “It is a question of time!” That is also what you say of the avant-garde….What was the nature of the modernness in these historical ruins? Could war be prospective?

During my trips along European coasts, I grew more and more selective, picking up only traces of the defensive system. Everyday life at the seaside had disappeared. The space I was charting with surveys and measurements of different types of casemates was the space of a different historical time than that of the moment of my trip; the conflict I perceived between the summer of seaside bathing and the summer of combat would never again cease. For me the organization of space would now go hand in hand with the manifestations of time.

This actual archeological break led me to a reconsideration of the problem of architectural archetypes: the crypt, the ark, the nave….The problems of structural economy had become secondary, and now I would investigate the Fortress Europe, which was vacant from now on, with an eye to the essence of architectural reality.

Observing the various casemates on the Atlantic beaches, the English Channel, and the North Sea, I detected a hub joining several directions. The concrete mass was a summary of its surroundings. The blockhouse was also the premonition of my own movements: on arriving from behind a dune I fell upon a cannon—it was a rendezvous—and when I started to circle the fortification to get inside and the embrasure of rear defenses became visible in the armor-plated door opening, it was as if I were a long-awaited guest….This game created an implicit empathy between the inanimate object and visitor, but it was the empathy of mortal danger to the point that for many it was unbelievably fearsome. The meaning was less now that of a rendezvous, and more of combat: “If the war were still here, this would kill me, so this architectural object is repulsive.”

A whole set of silent hypotheses sprang up during the visit. Either the bunker has no use other than as protection from the wind, or it recalls its warlike project and you identify with the enemy who must lead the assault—this simulacrum so close to children’s playful warring…after the real warring.

Besides the feeling of lurking danger, you can describe the structure by concentrating on each of its parts. The armor-plated door is no doubt the most disquieting, hidden by its thick concrete framing, with its steel wicket and locking system, massive and difficult to move, set fast in rust today, protected on its flanks by small firing slits for automatic weapons.

This narrow door opens into a watertight coffer in which the air vent looks more adaptable to an oven than to a dwelling; everything here bespeaks incredible pressures, like those to which a submarine is submitted….Several rear apertures carry cartouche inscriptions, supplying the support station number or the serial number of the work; others carry the name of the bunker, a feminine first name, Barbara, Karola…sometimes a humorous phrase.

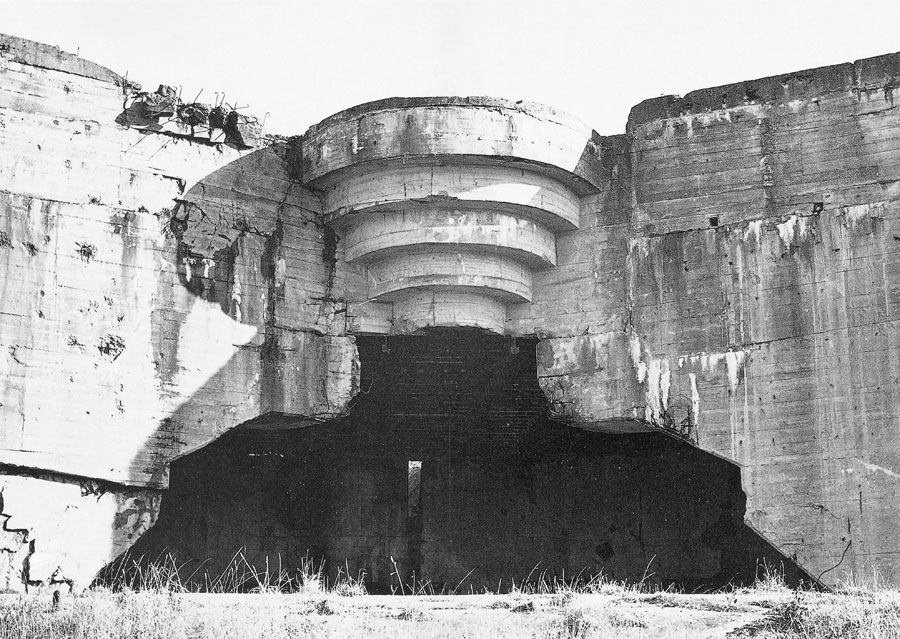

In the case of an element of the coastal battery, the embrasure is in fact the main opening of the structure; it is a cannon, a “mouth of fire,” a splaying through which the gun will spit its projectiles; it is the hearth of the casemate, the architectonic element in which the function of the bunker is expressed.

Major differences of existing aspects remain between the blind screen of the lateral walls, the passive imperviousness in the rear sections, and the offensive opening in front; as for the top, apart from the observer’s box, with the tiny staircase leading to the concrete nest, there are only the cannon’s gas discharge pipes emerging from the concrete slab sunk into the earth. Deconsecrated, the work is reversed: without the cannon, the embrasure resembles a door with ornamental reliefs, with vertical redans; the encircling of the “Todt Front” in the form of the tympanum above the rectangular opening becomes the companion piece to the porch of a religious building; through this makeshift entrance you gain access to a low, small room, round or hexagonal, covered with steel beams and having, at its center, a socle quite similar to a sacrificial altar. Trap doors open in the cement floor, through which access to the crypt is gained, where munitions were stored, just below the cannon’s base.

Going further back into the rear of the fortification, you meet once again the system of staggered nearby defenses, with its small firing slits—one along the entrance axis, the other on the flanks—with low visibility, through which the immediate surroundings can be seen, in a narrow space with a low ceiling. The crushing feeling felt during the exterior circuit around the work becomes acute here. The various volumes are too narrow for normal activity, for real corporal mobility; the whole structure weighs down on the visitor’s shoulders. Like a slightly undersized piece of clothing that hampers as much as it enclothes, the reinforced concrete and steel envelope is too tight under the arms and sets you in a semiparalysis fairly close to that of illness.

Slowed down in his physical activity but attentive, anxious over the catastrophic probabilities of his environment, the visitor in this perilous place is beset with a singular heaviness; in fact he is already in the grips of that cadaveric rigidity from which the shelter was designed to protect him.