The Great Indoors

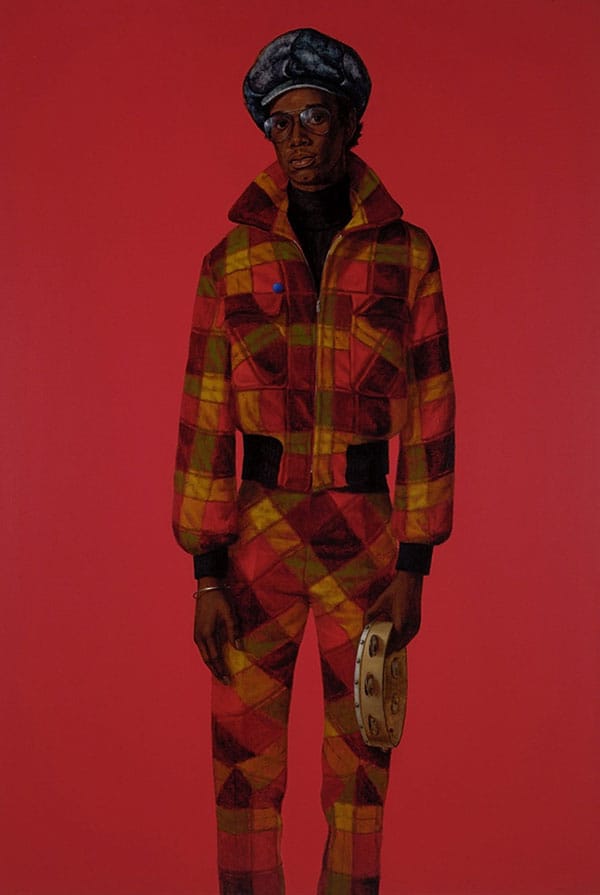

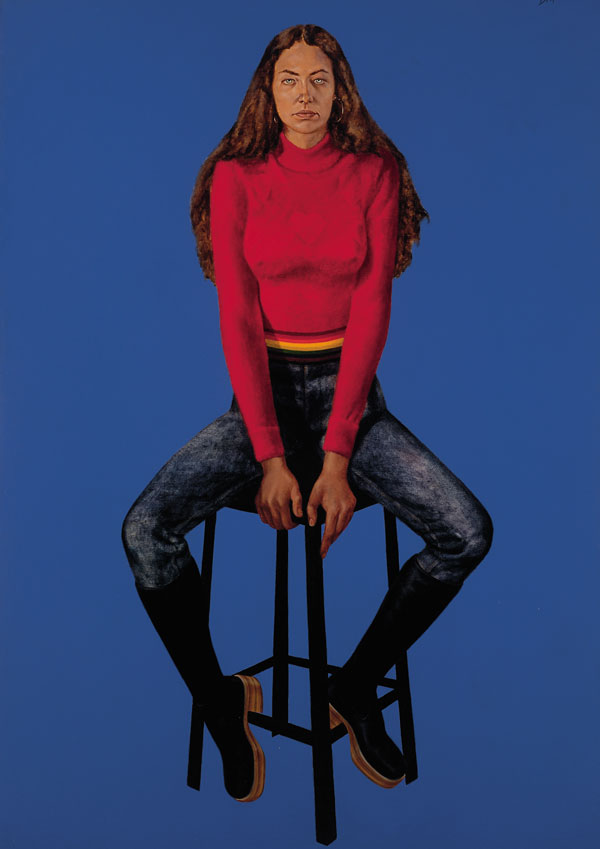

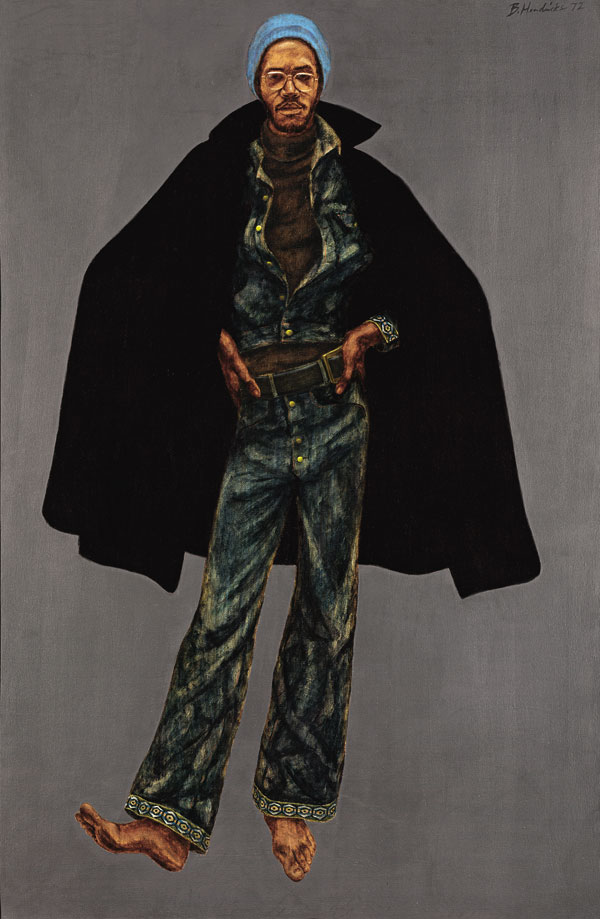

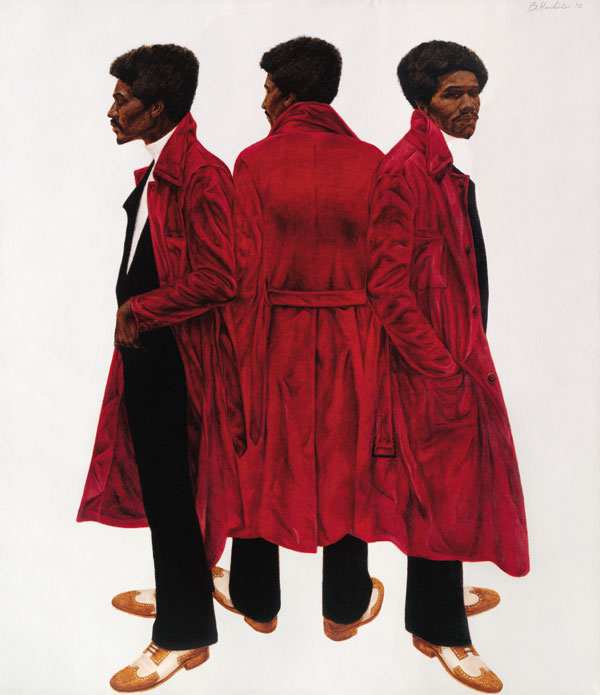

Though the people Barkley Hendricks paints are attractive, laid back, and worldly, don’t be fooled: These images have none of the indifference coolness implies.

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

How did you start painting portraits?

The Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia where I went to school had a portrait-painting focus, and I’ve been involved with drawing people since day one. There’s always been an attraction to human subject matter, but I was actually a landscape painter, doing more landscapes than figurative. The desire to be more involved with the human being overtook working outdoors because I had a disastrous time outdoors once. Continue reading ↓

“Barkley Hendricks: Birth of the Cool”, Hendricks’s first career retrospective, is currently on tour and will appear next at the Santa Monica Museum of Art from May 16 to Aug. 22, 2009. All images used with permission, © copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

What happened?

I was working on a painting and I stepped back about 10 feet, and the next thing I knew a gust of wind came and blew the painting right off. It pissed me off big time and I didn’t go back outside for almost 20 years. But then the Caribbean entered the picture. It’s warm and wonderful there and I’ve been going back ever since.

What’s the response to your more recent landscape painting compared to the portraits?

There’s the ignorance factor—people will say, “You paint landscapes?” For a time I had a narrow focus. I find that put me in kind of a one-trick pony bag. But when you think of Cezanne or Rembrandt, do you think of them just as figurative painters? I have an attraction to the great outdoors. When I have the show at the Academy of Fine Arts, [the amount of work] will grow even larger. Given that that’s my alma mater, it feels like an important place to set the record straight, so to speak. Also, my favorite instructor there, Louis Sloan, a major landscape painter, died, and I wanted to include work that would commemorate him.

I think people sometimes gravitate to portraiture because there’s this obvious narrative, or a person’s story suggested by the image.

Well, we’re humans. We respond to human beings. I don’t deny that, it’s a natural psychological connection. I certainly try to exploit that. But in terms of my areas of creativity I don’t want to be limiting myself to just that, because I’m aware of it.

Do you have any favorites among your different works?

Well, let me put it to you this way. I’ve shown at the Whitney three or four times. The most recent time, at the last Biennial, I showed photographs of Klu Klux Klan members I took in 1982. I didn’t like the images I had there—a bunch of assholes being racist. But I was proud that I was there in my photographic venue. I thought the images were good, I guess the jury thought they were good. I had focused on one of the only females who had the cone hat on. But the situation wasn’t such that I was all that happy because of the subject matter.

When it comes to portraits, how do you choose who you paint?

They’re friends and acquaintances. There’s a big body of images I’ve been fortunate enough to select from—people who know me volunteer or say, “Oh, I’ll sit for you anytime.” Personality and style of clothing certainly become a form of inspiration.

Is there a difference in working with a live model versus a photograph?

Recently it becomes a matter of convenience given the time—I’m busy. It’s a luxury to have someone pose for you for a length of time. There’s a human interaction that happens when you have a model for a period of observation.

What kinds of interaction?

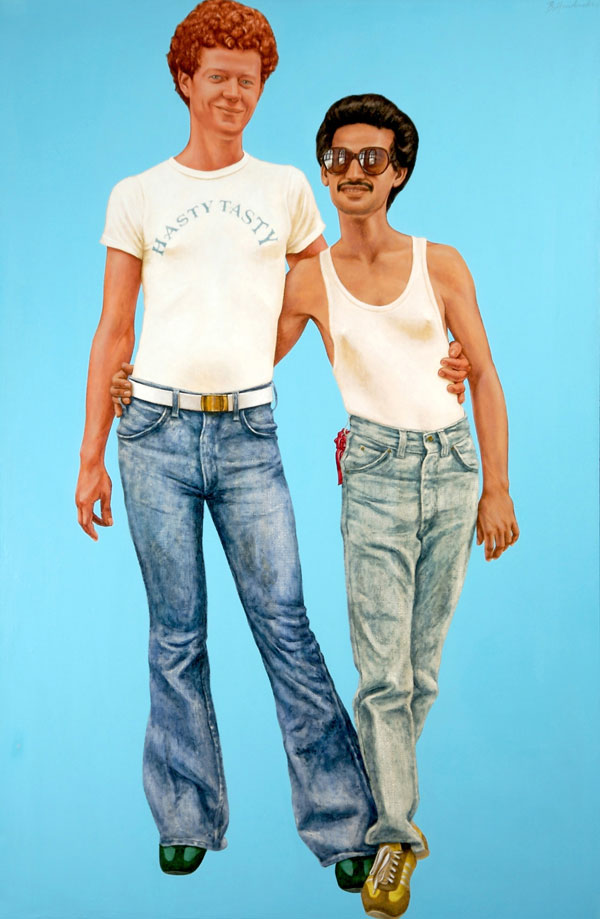

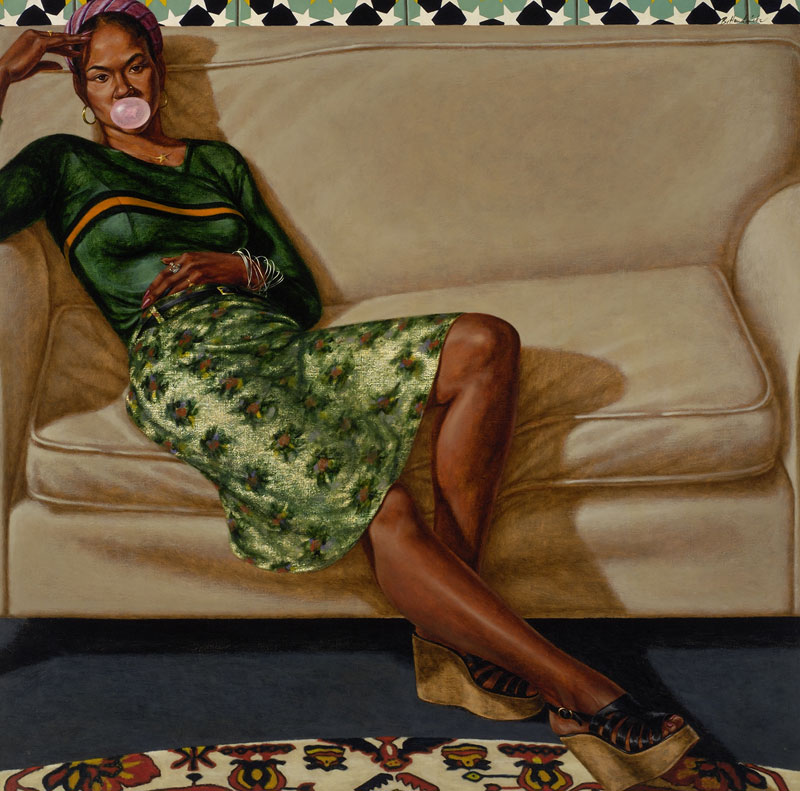

One of the images in the show is “Sweet Thang.” Her name was Lynn Jenkins and she was sitting for me, and during one of the sessions she was telling me a real heavy-duty sob story that had us both almost in tears and all of the sudden, she blew this bubble. That sort of cracked us both up. Right away I knew I had to put that in [the painting]. That’s one of the situations that can happen when you have a person in front of you. With a photo you have to stick to what you’ve put on film or digital, there isn’t that ongoing exposure like I had with Lynn, or with Jules [Taylor]. Jules and I were both at Yale and he came to my studio. He was always great to interact with; he’s one of my all time favorites.

I know you’ve traveled extensively in Africa. Which paintings did you do in Africa?

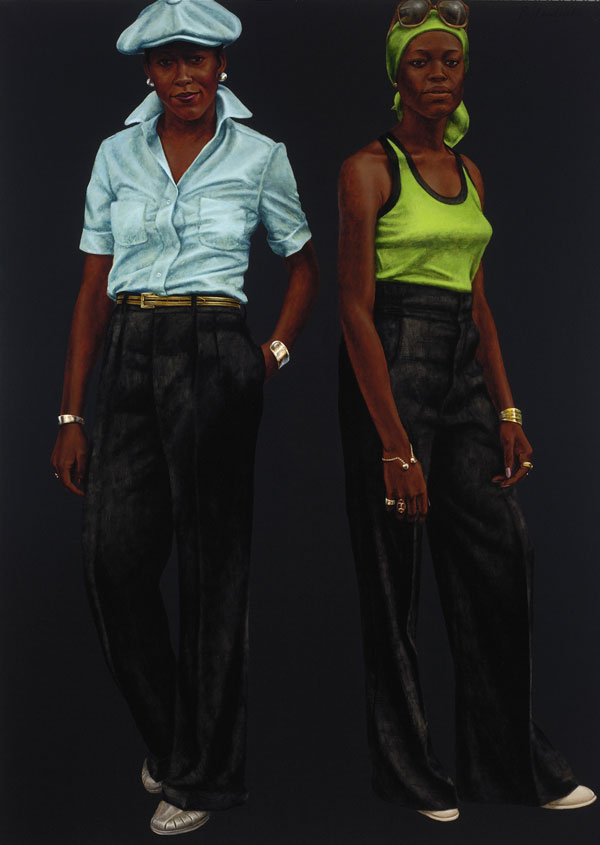

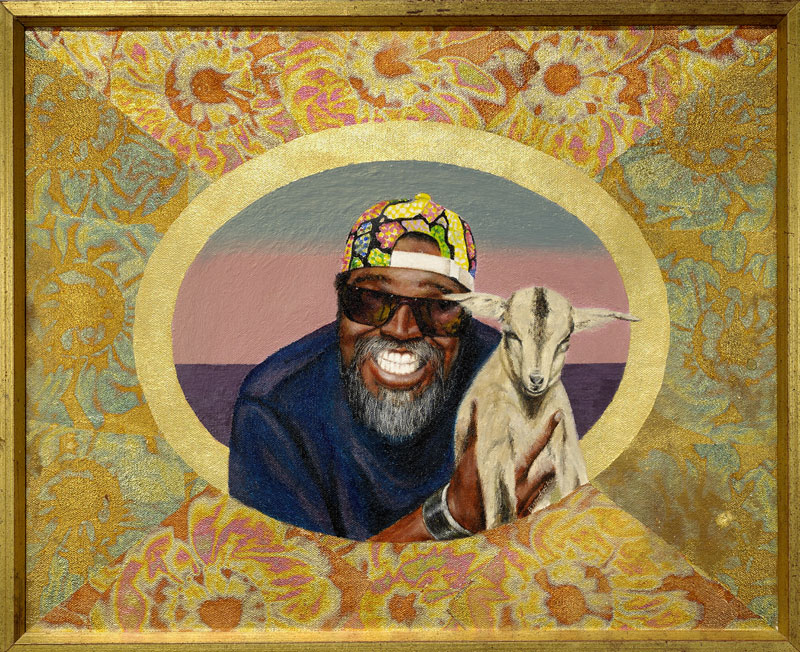

The “Lagos Ladies,” they were the cooks who were gracious to us while we were there. “APBs,” they were clearly African, but were in Paris. “Icon for Fifi,” I photographed her in Abidjan. And, of course, Fela [Kuti]. I photographed Fela in Norwich, CT, but he’s African.

Yeah, how did you end up being able to paint Fela?

I collected a number of his records when I was a disc jockey, and I had the opportunity to play his records over the years. I met him on a couple occasions. On one occasion, I had a chance to get backstage and converse with him. I told him I loved his stuff and would like to play my horn with his band. He said, “Yeah,” but I never got a chance to do that.