The Notion of Family

LaToya Ruby Frazier may be right that there is dysfunction in every home, but not every tense mother-daughter relationship receives such meditative and artistic consideration. The photographs she makes with her mother remind us just how unfamiliar we can be sometimes with those we call family

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

How did you begin collaborating with your family?

It started with me taking my camera home when I was 16. I was following my mom around Braddock Avenue. One thing you have to understand about the work is that what we’re doing is talking about our family lineage as women growing up in Braddock near Pittsburgh. Braddock is a community where Carnegie started his first steel mill. That brought a lot of immigrants as well as my family, and it was a flourishing place. The steel mills left in the ‘70s—they shut down and Braddock really suffered. Businesses started closing and people started leaving and by the time I was born in 1982, Braddock became an impoverished area and that’s when the crack epidemic started. Continue reading ↓

LaToya Ruby Frazier’s work is currently on display in the New Museum’s “The Generational” through July 5, 2009, at Higher Pictures in New York City through June 20, and at the Bronx Museum’s group show “Living and Dreaming,” opening June 21. All images used with permission, © copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

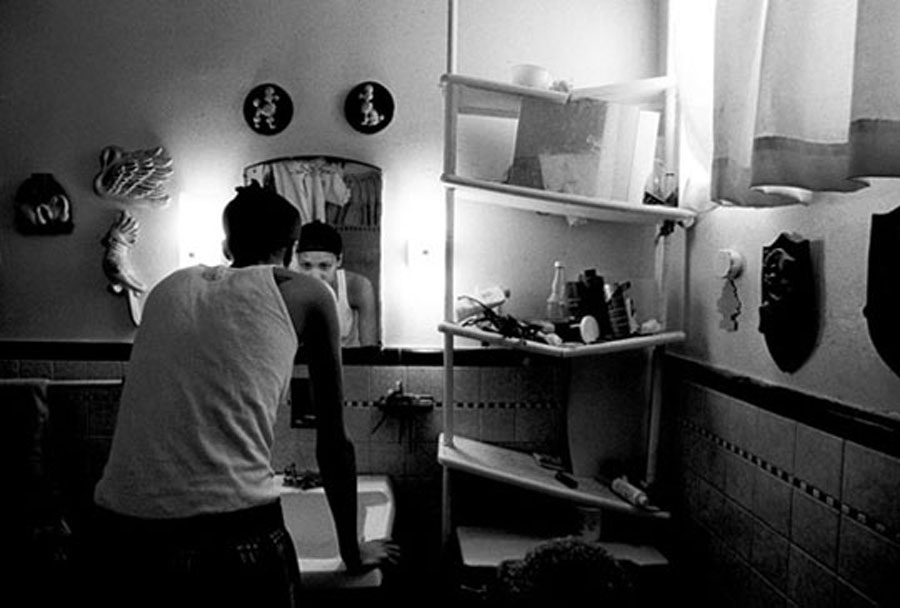

Anyone who lived in Braddock, their family was affected by the fact that there was no employment, as well as by the crack epidemic. My family suffered—my mother began her substance abuse with crack cocaine in the 1980s after I was born. Because she went to prison, my grandmother started raising me. Photographing my grandmother became a way to understand who she was as well as to try having a relationship with my mother. I followed my mother with a camera on Braddock Avenue to all the bars and to different people’s houses. Eventually, I’d bring the images home and she would interpret them in her way. She also began to become very active in directing shots and coming up with ideas. Right away there was an intuitive thing, but she and I had no type of relationship, we were quite estranged from one another and I wasn’t sure who she was. This became our space where we negotiated our relationship as mother and daughter.

I don’t know if you feel comfortable speaking on behalf of your mother, but could you give a sense of how she feels about the project or what she gets from working with you on photographs?

Certainly. The one image that made me realize that my mom really had an understanding of photography and it was more than just me shooting her, is the image of her exhaling the hit. She asked me to photograph her exhaling a hit of crack as she was smoking it. It was the one time I hesitated, but she was so sure. Later on as I came across it in editing, I didn’t want to deal with it. I finally put it in my first solo show and she came to the opening. The night before the reception she was explaining to me why she wanted me to take the shot. She said, “You know, I wanted you to take the shot because I wanted you to understand that you’re going to have to learn to deal with it—this is the way that I have been and this is the way that I am now.” She believes that photographs—not that they’re lying—but that they have the ability to capture what was somebody then, but is no longer that person a day later, or a month later.

It struck me right away because in Larry Sultan’s book, Pictures From Home, he gets into the same type of debate with his father over an image of his mother. That we were able to have that conversation about photography—and that it’s a conversation had by great photographers—opened my eyes.

So you see this work as part of a tradition of photography?

I love the work of Eugene Richards. His book Cocaine True, Cocaine Blue caused a great deal of controversy within the black community—Al Sharpton, everyone had something to say about it. When I started to make that image available [of my mother exhaling a hit], I realized that what my mother and I were doing had stumbled into something with a historical context. It’s one thing to be Eugene Richards and document cocaine use in a journalistic type of way, but what me and my mother had done was taken it a step further than that. We’re saying that we have power and agency over creating these images. It’s a conversation that we’re internally having as mother-daughter as well as socially without judgment.

Does your sense of history and photography impact the way you shoot or print your work?

I’m formally trained in the history of photography, my mother’s not trained, so it was important for me to take the theory I’ve learned and apply it to real-life experience. The aesthetic of the work and the reason it’s gelatin silver print comes from my initial interest in the FSA from the ‘30s. The work of Walker Evans, Dorothea Lang, and Gordon Parks was always a fascination of mine. There’s a history and lineage of photographers photographing family looking at photographers, like Emmet Gowin, Nicholas Nixon, Lee Friedlander, Sally Mann, and Doug Dubois, who was also my mentor. I’d always wondered what it would look like if the families were photographing themselves. Often we see the photographer be the photographer and the subject be the subject, but in this series my mom operates the camera, and she photographs me.

What about your grandmother, how does she fit into your project?

The picture of my grandmother chain smoking in “Pall Malls 2002,” with all the porcelain dolls around her—that is the image that led to my grandmother and I making a portrait on the floor of my hair in pigtails, the way she used to braid my hair when I was little. I had her redo it and then we made a portrait together on the floor. In the work, I am in the middle of my mother and my grandmother—I am the future. My grandmother indicates the past, and my mother indicates the present. My grandmother, no matter how much I’d photograph her, would never talk about family history—she wouldn’t tell me where my family was from, I don’t even know who my grandfather was. All these things remained a mystery. Photographing her was my way of trying to know what these mysteries were through her familial gaze. She’s kind of like Ralph Eugene Meatyard’s book The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater with the family members wearing masks, even though it’s my grandma’s real face. She was a sealed vault that concealed our family history. Photographing her deals with a lot of my frustrations about our lineage.

How do the photos and photo shoots happen?

When my mother and I made the portrait “Mom 2007,” we’d photograph in our bedroom and take the mattresses and push them up against the wall, and then put comforters over the mattresses. We’d turn it into a studio space, I’d set up my lights and my camera, we’d put on some music, maybe open a couple of beers and we’d rotate back and forth taking pictures of each other. Sometimes we would imitate one another or take pictures together on a timer and what would happen was we’d start to talk about things that, for some reason, our personalities wouldn’t let us [talk about] when we weren’t facing the camera.

We both have so much angst and anger with one another and most of that is due to the fact that my grandmother had to play the role of mother to me, which made us more or less rival siblings. Because we’re really strong-willed women often we butted heads. But once we let our guards down by laughing at how similar we are or the way we act, we got to know each other as mother and child. There’s a lot of humor behind these things even though they come off as serious.

How has doing the work affected your relationship with your mother?

One thing that I’ve learned through making the work is that you only get one mother, and so either you start accepting things as they are or you ignore them—but that would be a tragic gap in my life if I did not pursue some type of relationship. There’s always a lot of conversation that photographs lie, but for me, and what I’ve done, the images have a way of telling the truth. You can look at those images of me and my mother standing side-by-side and you can tell that I’m guarded, I’m more controlling. I’m more serious because of the circumstances, how I grew up and what I went through in my community. I can’t lie about that—it’s there. I’m not cold, I’m not distant, or detached, but I certainly come off as guarded after dealing with a lot of violence and abuse in my household. My mother and I have swapped roles as mother and daughter, but ultimately, she is my mother. She has yet to admit it, but this is also maybe her way of trying to reconcile.

I think that everybody has some level of dysfunction in their house. It’s just that they don’t want to acknowledge it. But people come up to me and talk to me about how their mother, father, or uncle, are alcoholics or drug addicts. After I give a lecture I’ve had total strangers come up and talk to me about it.

Did you set out to make work that was approachable, or was that a surprise?

It was a surprise down the road to realize people actually liked the work. Socially we are taught to separate private and public space. Speaking publicly about what has happened in my family behind closed doors has corrected many misconceptions and stereotypes. It has also bridged many similarities cross-culturally about family.

What are you working on now?

My grandmother died in January. My mom and I have been trying to deal with that in our work, but we haven’t done much in the past three months. At my grandma’s viewing I created an elaborate installation with all her porcelain dolls and portraits that we had made together around her body. I think that’s the end of a chapter as the work started with my grandmother. Currently I continue to work on my first book, The Notion Of Family, and I am in discussions with publishers that are seriously interested in publishing the book.