The Weight of a Social Network

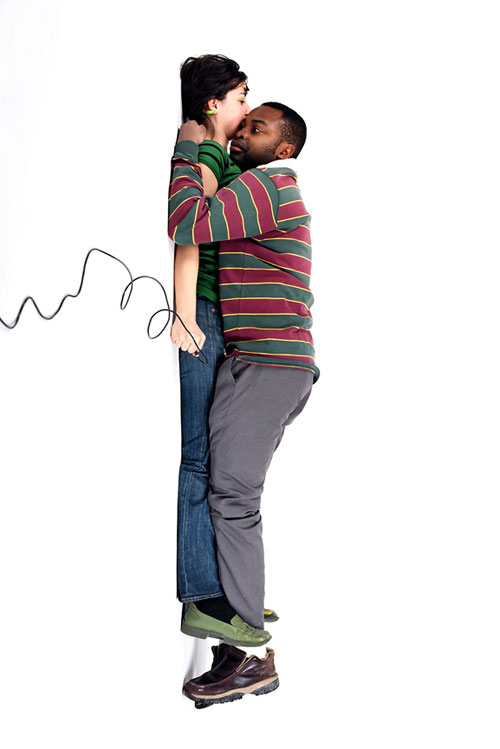

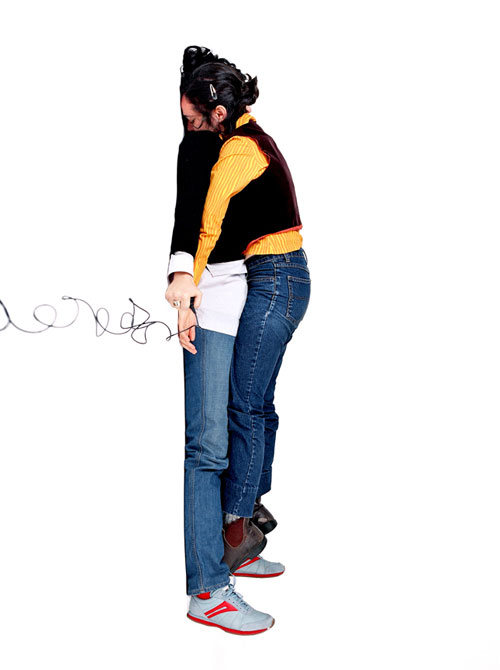

Physical contact between strangers is one of society’s great taboos. Photographer Alana Riley breaks that barrier by asking friends and strangers to cede their personal space both in their workplace and in her studio.

Interview by Nozlee Samadzadeh

How did “Support System” come about? The idea for “Surrender”?

The idea behind “Support System” came about during a highly social period in my life. Originally this series started out as a performance exercise exploring interpersonal relationships in which I asked various people in my immediate social circle to lie on top of me. The first two people I tried this with were my mother and father, followed by friends and other family members. The idea stemmed from a desire to manifest in a literal sense the figurative weight of the people who make up my social network, and to document this as a series of individual portraits. The photos revealed the subtle tensions and physical responses of each subject in this inherently awkward act. Continue reading ↓

All images used with permission, © copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

Following this series, featuring family and friends, I became interested in the dynamic that was created from this unusual physical interaction and decided to explore this further with people I did not know. When I approached strangers with this idea, I chose to leave open how they wanted to interpret “lying on me.” With this proposition, a variety of reactions became evident in these images: some people would barely touch me, propping themselves with their hands and feet, while others lay with evident comfort. I found it interesting that some of the subjects were more aware of the camera and the actual taking of the portrait, while others were more obviously concerned with the physical interaction. This series with strangers became the final result of the project and over the course of two years I photographed over 30 people.

I started the “Surrender” series just as I finished “Support System.” I felt I had been asking a lot of my subjects, these people I didn’t know, through their participation in that project, and even though I was present in the photos, I was very passive and more like an observer than a participant. I wanted to explore again this idea of ‘weight’ and how we figuratively ‘carry’ others within relationships. As with “Support System,” the “Surrender” series plays with this idea of supporting others, while at the same time questioning the role of both subject and photographer. Though my work is performative in the sense that I am present within the action taking place in the photographs, my interest also lies in the questions that arise from taking one’s portrait.

Do you see the two photo series as related?

Yes, very much. Initially I wasn’t resolved with the “Surrender” images and for a few years put aside the idea entirely, having never printed anything more than the contact sheets. As other bodies of work developed, I felt “Surrender” was important to balance out this dynamic that I was exploring in human relationships. Concerning the notions of surrender and support, one cannot function without the other: there must be a support in order for one to surrender. I think the titles of the series could almost be interchangeable in that sense.

How do you find your subjects? Describe a shoot.

In “Support System” I came upon the subjects rather randomly: from stopping people on the street outside my studio in downtown Montreal, to word-of-mouth through people who heard of the project. Generally a shoot day began with some mental preparation; it seemed that no matter how many people I had photographed in the past, the process of asking strangers was always the looming challenge. I would approach people with the idea that I was working on a project involving photographs with myself and people I do not know. If they were open to at least this, I would then explain that the idea was for them to lie on top of me for the duration of a roll of film (10 frames with a medium-format camera). I would offer them a copy of the final photograph in exchange. In “Surrender” I originally sought out people in random work environments, but as the series evolved and I returned to it nearly three years later, I decided to include people that I had come to know in the place of their employment, such as my dentist. I thought that this dynamic of surrendering oneself to another is often at play in these relationships. There is a question of trust involved. As this series was more physically demanding than “Support System,” I did not shoot many photographs while I was carrying them, usually taking just enough images to get them to the point where they were relaxed, and not laughing.

Photography is traditionally an art that involves distance between artist and subject. What made you want to not only enter the photos, but do so in intimate contact?

When I first became interested in photography I had a hard time pointing a camera at someone, so I would only photograph objects or environments. Ironically, I hate having my picture taken, but I feel that by placing myself within the photograph was partly how I found resolution in executing portrait photography. It seemed somehow less intimidating to photograph someone if I was participating with them directly. I believe that portraiture is very much bound by the relationship of the photographer to his or her subject and this is something that I question and explore a lot in my work.

Why are the faces of the workers you carry in “Surrender” turned away?

I was asking people to let go completely and to ‘surrender’ themselves to me not only physically, but also to the camera, and inherently to their own portrait. I think we do this, in a sense, when we let someone take our picture; there is a certain amount of relinquishing and trust involved. So while the subjects and locations were of interest to me, the photograph was less about their personal identity and more about exploring this relationship dynamic. I think it was a challenge for most people to not look at the camera and to really let go.

Why are the photos in “Support System” turned 90 degrees?

I wanted to alleviate the tension and negative connotation of being ‘weighed down’, while at the same time presenting the photographs in a traditional portrait format. I saw this series as exploring how individuals come together, how we relate and interact with one another. It is still obvious that we are lying down and I wasn’t looking to negate that aspect, but I wanted to shift the viewer’s perception of gravity, allowing the figures to exist in this nowhere time and space.

Is the lack of contact between strangers and between service providers/consumers in our culture problematic, or necessary?

I definitely don’t think it is necessary, nor is it entirely problematic. I think it is subjective. I personally prefer to engage on a certain physical level, even if it is simply addressing someone and looking at him or her when we are having an exchange. I have worked in the service industry and know what it is like to deal with many people in a day, and it’s easy to lose the feeling of having any individual connection. Gestures become robotic. I know many people who don’t see the point in having an authentic human exchange in our countless daily moments of business interaction. For some, it is simply perceived as superficial to address someone you don’t know with a more intimate exchange. But I am a fan of these small personal gestures. So much of our everyday is made up of these brief moments of connection. I have always loved how in small towns, people smile and greet you unprovoked, when merely passing on the street. Of course this just couldn’t happen in big cities, but there are still small ways in which we can extend ourselves. Life is made up of the little moments like this.