To Brooklyn

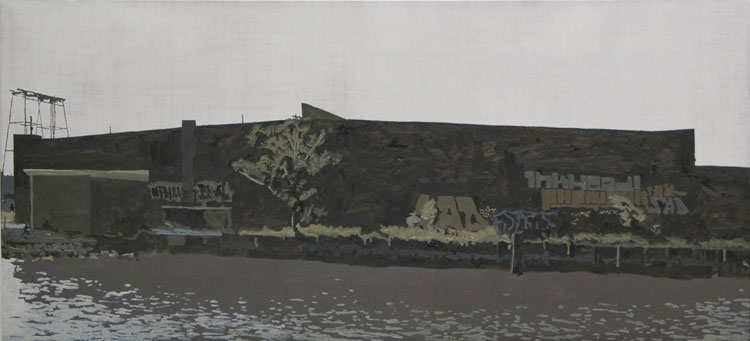

No longer thriving with industry, Brooklyn’s industrial waterfront is now being remade by developers and planners who have cafés and green spaces and expensive rents on the brain.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

How long have you lived and worked in New York?

I’ve lived and worked in Brooklyn for almost four years. Brooklyn has a derelict, almost subversive appeal to me—although part of greater New York, it seems to often hold a history independent of Manhattan. I think what draws me the most to Brooklyn is the sense of distinctive neighborhoods and the cultures which they contain. I enjoy the sense of community and the gradual evolving of urban planning that is a silent influence in all of our lives. In Manhattan, although there are definite neighborhoods as well, it feels more seamless and dense, more anonymous and with less character. I also am attracted to the largely transitional feeling of several neighborhoods, which is at once fascinating and terrifying. Continue reading ↓

All images courtesy Greg Lindquist, all images copyright © Greg Lindquist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

Men and women don’t play much role in your landscapes. We don’t even see cars. Is development a faceless process?

I am aware of this issue and intentionally don’t depict people—I’m interested in how these scenes in their material function implicate human activity. Also, I think the lack of people tends to heighten their somber quality and suggest an overall and impending sense of absence in the landscape. But, as you ask in the question, Brooklyn’s development is a faceless process insofar as the developers deciding how this building occurs aren’t the ones you see onsite executing these decisions. There’s a real disconnect in this process, it seems. Often, also, the community has little control over these decisions and the developers disregard their concerns, valuing economic factors more than social issues. I think that’s also evident in the design process that’s lost in computer renderings of proposed buildings where these renderings look nothing like the final built structure.

New York’s constant is change, always tearing down and building up, and it always has been. Do you see yourself documenting the here and now, or something older?

That’s very true and I think about this a lot walking around the city and observing details where you can see the rich layers of history through what remains visible to suggest something no longer present. It’s a palimpsest of sorts. I see my work as a segment of a larger historical continuum. Such artists as Joseph Pennell, for example, captured New York in a previous era of building, in this case the building of Manhattan’s skyscrapers. Now the major growth is residential and it engages many sociopolitical issues, such as population growth, the end of the Industrial Revolution, and the outsourcing of production through globalization. So, yes, this is the here and now of New York and for the United States for that matter as New York provides a pretty good paradigmatic snapshot of the United States at large.

I wouldn’t call these cheerful paintings. What are your personal feelings about the evolution of the Brooklyn industrial landscape?

It’s a very complex subject with equally conflicted feelings. I recently saw a spray-painted stencil on a building’s façade in Williamsburg that read “Don’t fall in love with buildings, they’ll break your heart.” I kind of took that to suggest the rampant speed at which Brooklyn is being transformed. Everyday a new building seems to sprouts up from an empty lot and some beautiful warehouses have been demolished rather than preserved. I feel the sadness in this loss, but as you said, this is nothing new. Yet at the same time, I am fascinated by the building process, and I hope this is reflected in my choice of materials in the paintings: the metallic paint and stainless steel grounds. But perhaps the feeling at its core is one of control. I feel a helplessness about this transformation of the landscape and one way of feeling some degree of control is by documenting the in-betweens, making something temporal permanent. It’s a way of memorializing the ever-changing landscape.

Your work sends me very far back, without much room for modernism. Who do you look to?

Most recently, I spent the last year studying the work of three contemporary American landscape painters (Benjamin Edwards, Will Cotton, and Rackstraw Downes) for my art history thesis, connecting their approaches to the work of the 19th-century Hudson River School (such as Frederick Church, Thomas Cole and Asher Durand). But also, I have been a longtime admirer of such painters as Georgio Morandi, Fairfield Porter, Tintoretto, Anselm Kiefer, and Luc Tuymans. I also studied the landscape etchings of Rembrandt in grad school and while working as an artist assistant for Ryan McGinness, learned about the business aspects of art, how to be organized, how to be relentlessly producing as well as being more aware of process. Ryan became a bit of a mentor for me and an inspiration for fully pursuing one’s aesthetic vision.

Will it always be Brooklyn?

At the moment, I feel this body of work reflects my clearest articulation of the subject matter through its form. Although I have been using the same complementary colors for mixing for over seven years, the color palette has gradually developed to its current somber state. In the past couple months, I have started to shift my focus to other phenomena in the landscape, such as strip mining out west. I visited some exhausted surface mines for copper ore in Arizona and was amazed by how bizarre these shaved-down mountain tops look and how manufactured and manmade they appear. Basically, they look like large geometrically concentric striations around hills and then large pits in the ground. In Bisbee, they have become integrated into a geography including tourist attractions and I find these strange dislocations of the manmade and natural intriguing. It excites me to think about these new sites and their accompanying different color palettes.