We Shall

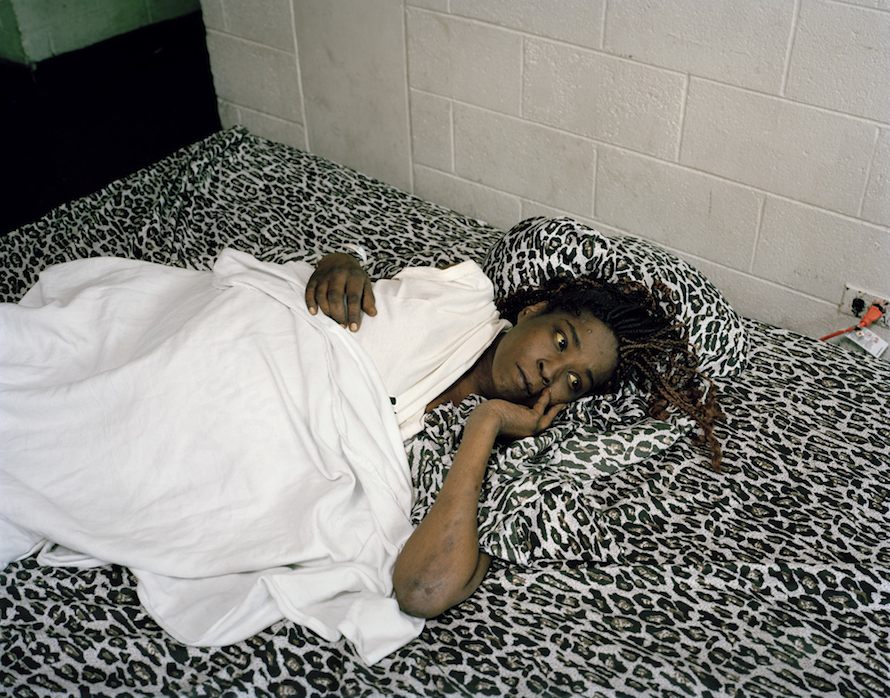

Paul D’Amato’s portraits, collected in the masterful new book “We Shall,” represent 10 years of photographing the west side of Chicago.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

The Morning News: What’s the genesis story of this book?

Paul D’Amato: The book is two things, maybe three: First, it’s a distillation of work that has been ongoing for 10 years in a number of neighborhoods that comprise the west side of Chicago. Secondly, it is an exhibition to accompany an exhibition that took place last fall at the DePaul University Art Museum, and thirdly, it was designed to do something that would augment the experience of the show. There are a number of instances in the book that reproduce alternate—one to two other—versions of images in the exhibition to illustrate the fundamentally collaborative and performative nature of portraiture. Continue reading ↓

All images used with permission, © copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

TMN: The people in the portraits: were they strangers to you when took their picture? Are they strangers to you now?

PD: We all start as strangers to one another. So yes, the pictures have to start there but my process is to always bring prints back to my subjects. I do this to thank them for their time, which in some cases is considerable, but to also see if we might make a better picture. There are a number of people I have photographed repeatedly for years, enough so that various images of them could comprise whole chapters in a larger book of the work.

What I find particularly mystifying is that, as often as not, the very first image of a subject—when we were strangers—is the best one. But then again, with some people, the images keep getting better as we get to know each other more.

TMN: How do you know a great portrait when you see one?

PD: A great portrait is one in which the image resonates with a kind of energy that makes it difficult to walk past or turn the page. It’s a smoke-and-mirror act because, like all of the other images—the many other less successful images—it’s still just ink on a piece of paper. Achieving this kind of presence in which this ink comes alive is so elusive; it’s probably the reason that I keep making pictures.

TMN: How much luck goes into your work?

PD: No more than any other successful endeavor. Everything is the result of work.

TMN: You appear to care a lot about light and visual lines. How much is it for craft, how much for meaning?

PD: I care about light, color, composition—all of the formal elements of the visual arts—the same way a writer loves language. Craft is technical. Form is integral to how a picture works, what it means, how it makes the viewer feel etc. Ben Shahn called form “the shape of content.”

TMN: Does a camera connect you to other people?

PD: Yes. Making these connections is its own reward, whether I’ve made a good picture on any particular day or not.

TMN: Really? Don’t you ever want to leave those connections behind and take off for the next thing?

PD: I leave lots of connections behind as an artist and as a person. You sound like you and I stay in touch with lots of others as well. I get involved with some of my subjects a lot more than others—to the point where we’re buying Xmas presents, etc.

I’ve been making this work for over 10 years now, and I’ve known many of my subjects that whole time and am still in touch. I see many of them a lot more than I see most of my family.

TMN: When are you most challenged?

PD: Photographing and printing is pure, unadulterated pleasure, but editing, though engaging and interesting, is challenging. Who stays, who goes, the title, etc.—that’s tough. That, and money.

TMN: If a portrait is a negotiation between the subject and the photographer, how often do you think you win?

PD: It’s not about winning. It’s a dance.