Woman in My Heart

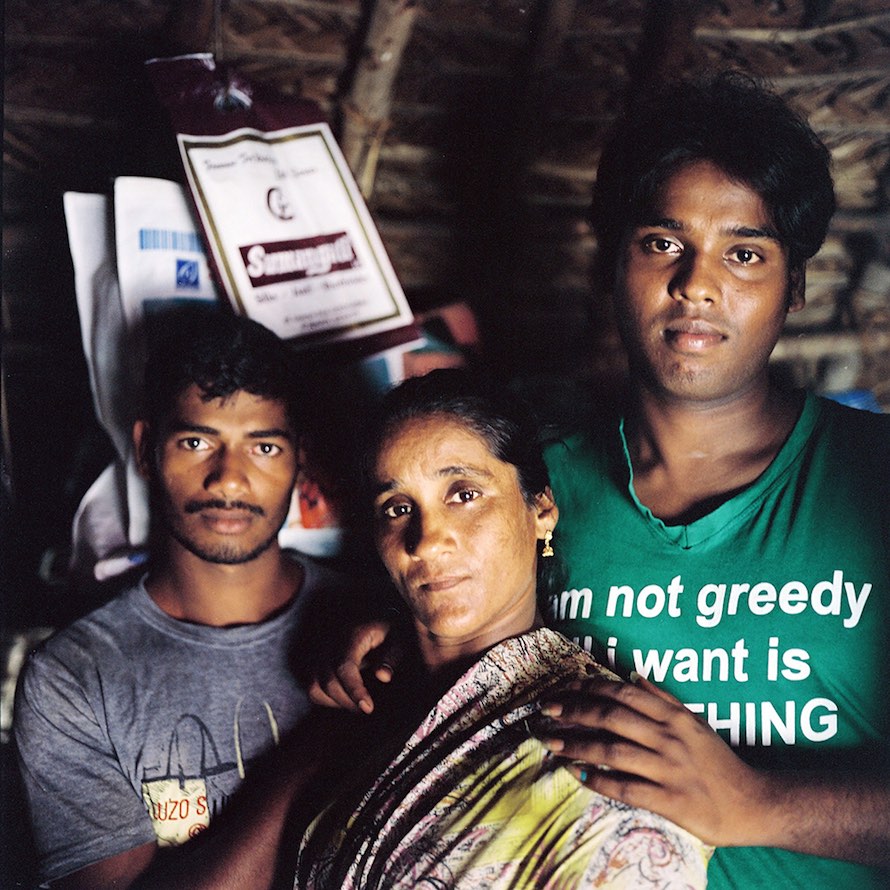

Portraits of a queer community in South India treat gender, biology, art, and family with emotional nuance—no exoticism in sight.

Interview by Karolle Rabarison

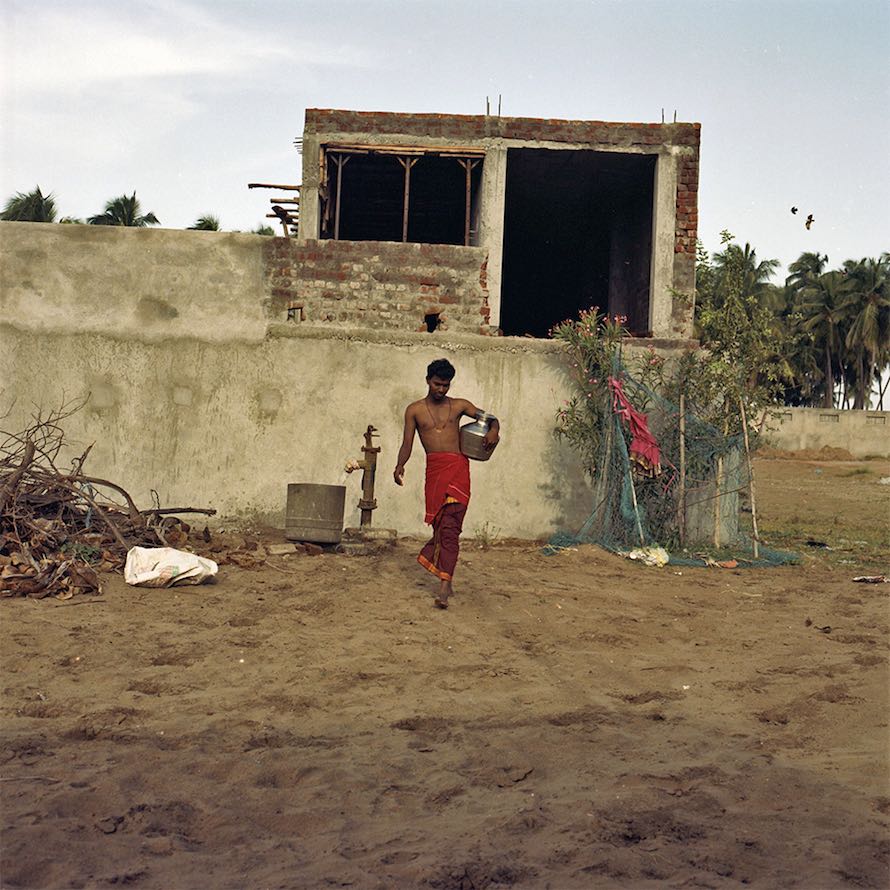

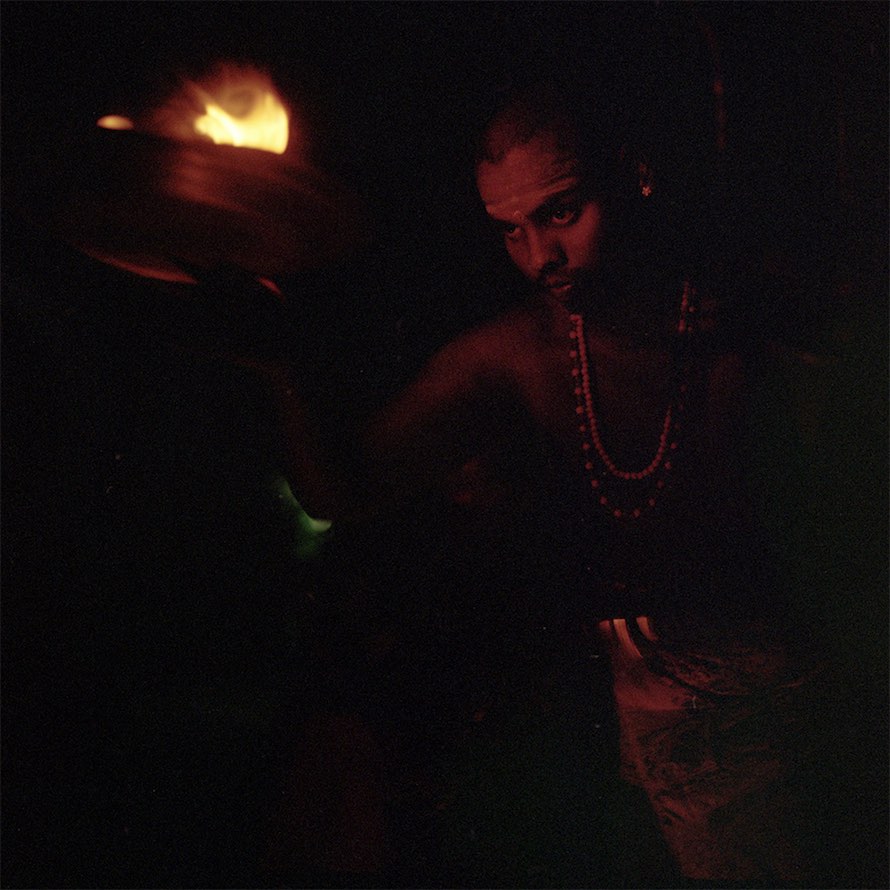

In March 2013 Feit was invited to Tamil Nadu to document Mayana Kollai, a festival organized by kothis that celebrates the Tamil deity Angalaamman. Kothis are individuals born with male biology who may manifest as men in everyday life and identify with female roles and behaviors among peers. Photos of the festival sparked what would become her series “A Woman in My Heart.” Read the interview ↓

All images used with permission, copyright © the artist, all rights reserved.

Artist interview

The Morning News: You spent a whole year documenting the lives of kothis in Tamil Nadu, and recently returned to work on more images and interviews. What prompted the follow-up trip?

Candace Feit: I lived in New Delhi from 2009-2011 and had spent several weeks at an artist residency in Tamil Nadu, and had been back there for stretches of time to continue that project. When a writer friend asked me if I wanted to join him to photograph the Mayanakollai festival in March 2013, I jumped at the chance to go back to Tamil Nadu.

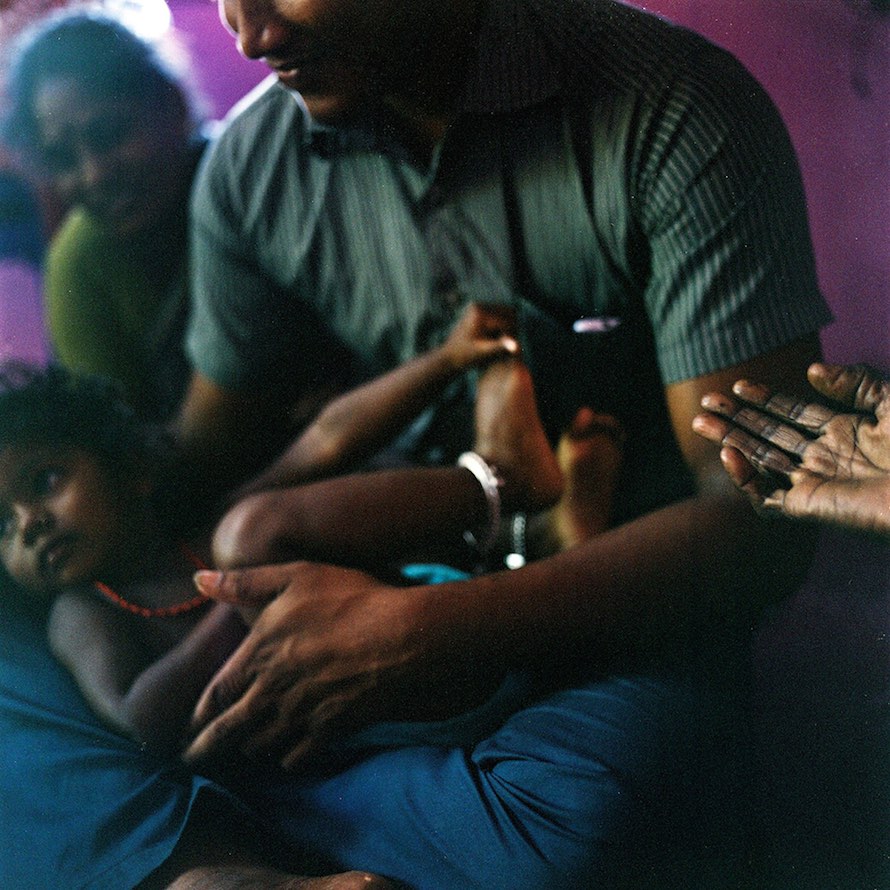

I spent about a week with the community while they were celebrating the festival. I felt very connected to the people I was meeting and felt like I had made some strong photographs there. But I also thought it was a shallow approach, showing only one very small part of the life of this community. I wanted to get a deeper understanding of how some of the people I met lived their daily lives and navigated expected roles within their families and the broader community—especially since I knew that several of the kothis I had met were married and had children, or were being pressured by their families to do so.

So with that goal in mind, I raised money via Kickstarter for a trip back, which I took in November 2013. After that trip, I had a better understanding of the relationships within the kothi community and how the kothis are able to find ways to express their gender identities while also maintaining more traditional male roles within the society.

There are so many subtle ways that people express their gender identity, and there are not enough stories showing emotional depth in the media right now. I want to continue to photograph this group as many of their lives change. I just went back in September to spend a week in the Devanapattinam, a village near Cuddalore. One of the kothis I’ve been photographing has been being pressured to marry, while another married and has a baby. There are kothis whose parents accept that they will not marry, yet they will still struggle to gain acceptance of a same-sex partner. And there are others within the extended community who soon hope to begin the process to transition to female.

TMN: Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code criminalizes homosexual intercourse. In 2009, the Delhi High Court ruled Section 377 unconstitutional in a move many gender activists considered a huge step towards equality. In December 2013, the Supreme Court overturned the lower court’s ruling and upheld Section 377. Even more recently, India’s new government filed objections to an April 2014 Supreme Court ruling to grant legal recognition of a third gender. As you’re working amid this struggle for recognition and equal rights, would you consider yourself an activist?

CF: This is a tough question. There are many true activists putting themselves at risk and who have dedicated their lives to fighting for these rights.

I would say that, if anything, this work is a subtle form of activism. My goal with my work is to connect with people and try to tell their stories in a human way. Through these connections and stories, something—attitudes, behaviors—might slowly shift. So first and foremost, I am an artist and storyteller, and I hope my work does affect change, however slight.

TMN: What trait do you most admire in the kothis you met?

CF: So many. First, the fact that many within the community have been patient beyond expectation—kind and welcoming and generous with their time. I admire the closeness and support that they provide one another. Several of them are activists, and I very much admire their dedication to educating the wider community on LGBT issues, including police sensitization, HIV awareness, and counseling, among other things.

TMN: Andrea Lee describes exotic as “a simple conflation of strangeness and desire” and writes, “There is always something willfully stupid about ‘exotic’: two-dimensional, fundamentally dull.” How do you maneuver between reality, the caricature of India as exotic spectacle, and dignity for individuals who are outsiders in their own community?

CF: This is a question that is often on my mind, and a big reason why I have felt so determined to keep going back to this story and this group of people. The caricature of India is everywhere and so accessible to a photographer, but it is a trap. And it is dehumanizing. India (as the rest of the world) is more than one thing—more than women in brightly colored saris, more than Sadhus with long dreadlocks, more than the Taj Mahal. To see what is beyond this exotic stuff on the surface takes time and patience. It is hard to slow down long enough to connect with people.

While photography can be a trap, it is also a tool to figure it all out. One way I navigate this challenge is to try to be at ease where I am, and while committed to that ease, respecting boundaries and making sure I am as honest and open as possible with people I meet. No matter where you are, it’s a huge thing to ask people to welcome you into their lives and answer questions they might find intrusive, all while having a camera pointed at them. I think shooting in film helps a lot. It forces me to compose more deliberately, and it takes away the compulsion of constantly looking at images while shooting. Working slowly is my attempt to combat the willful stupidity with some thoughtfulness.

TMN: When was the last time a photograph disappointed you?

CF: The thing that disappoints me in a photograph is missing the moment—particularly a moment of intimacy between people, when the guards are down and when something is revealed in their face or body language or relation to another person. I’m always trying to anticipate and really see these moments, so feeling like I missed one is very disappointing.

TMN: Where are you taking your camera next?

CF: I recently moved from Johannesburg to New York, so I have been settling back into life in the USA after almost a decade abroad. I spent the summer working on photographing county fairs and will continue to try to broaden the kothi project into a gallery show and book.