Powerlifter

Traditionally ostracized in the weight room, women who dare to lift weights discover strength they were previously denied.

Until 1986, the world’s strongest woman, according to the Guiness Book of World Records, was an Austrian named Katharina Brumbach. If you’d been alive at the turn of the 20th century, you might have known her as Katie Sandwina, the five-foot-nine, 210-pound circus strongwoman who simultaneously earned her stage name and set the women’s world record when she out-lifted the famous bodybuilder Eugene Sandow in New York in the early 1900s.

The circus was Sandwina’s life: It led her to her career, her husband, and her future home. Both her parents earned their living as strength athletes in Germany, and she grew up performing with them. As part of her routine, Sandwina would challenge any male audience member to a wrestling match. The man who could beat her would win 100 marks, or about $660, accounting for inflation. Max Heymann, an aspiring acrobat and the first volunteer, claims to have fallen in love with Sandwina after being thrown to the floor and carried out of the ring in her arms. Late in his life, Heymann claimed the lovers eloped shortly thereafter, though historians dispute that. At any rate, they were soon touring Europe and the US with their own act. As part of the finale, Sandwina would lift her 165-pound husband overhead with one arm.

Although the couple performed in the US together, Sandwina didn’t earn celebrity status until she signed on for two seasons with Barnum & Bailey’s Circus at Madison Square Garden in 1911 and 1912. In New York, Sandwina rocketed to fame, quickly becoming a poster girl for the adage “beauty is strength; strength, beauty.” According to Kate Carew, a contemporary newspaperwoman who interviewed leading celebrities like Sarah Bernhardt, Picasso, and Jack London, Sandwina was “as majestic as the Sphinx, as pretty as a valentine, as sentimental as a German schoolgirl, and as wholesome as a great big slice of bread and butter.” A year later, another reporter named her “the most perfect specimen of womanhood that has ever been seen.” His words, far from original, became part of a common refrain: Sandwina was described everywhere as perfect, ideal, the consummate woman.

Given the 21st century preference for super-skinny women, it is hard to imagine that a sturdy, 200-pound strength athlete, with muscles only softly defined, could inspire such veneration. It is hard to imagine now that a woman who wrestled men and picked them up for a living, a woman who drank beer at lunch, could be viewed as a paragon of femininity. But she was.

Weightlifting has long occupied a liminal space between spectacle and sport. It is an Olympic-level activity, yet many circuses still have a “strongman” act, in which muscle-bound men with gimmicky stage names like Hercules exhibit what’s billed as freakish or superhuman strength through stunts—juggling iron rings, tearing phone books in half, bending metal bars.

All sport is, of course, part spectacle: Think of the crowds that flock to stadiums every weekend for fall football, the basketball tickets that sell out within minutes, the soccer players who strive to charm the spectators with flashy moves, the over-the-top halftime shows. “Sport” once meant “entertainment” or “fun” for a reason—for centuries, its primary goal was to amuse, delight, and divert populations—not to teach willpower and team work and insure longevity. And yet soccer, basketball, and tennis players, swimmers, skaters, and runners, are treated as legitimate professionals. They don’t perform in circuses nor are they forced to demonstrate their skills in increasingly bizarre and inventive ways.

Strongwomen like Sandwina, once a staple in the Victorian circus, were considered particularly freakish not because of their prodigious strength, but rather because of the implications of that strength on traditional conceptions of gender. What made Sandwina remarkable was not that she could lift 286 pounds overhead, but that she was a woman who could lift 286 pounds overheard. What turned her into a sensation was the fact that she was an attractive woman who could lift 286 pounds overhead. Guinness listed her as the “world’s strongest woman with the perfect hourglass figure.”

In this regard, little has changed in the past century. Toned yet tiny fitness models like Jen Selter and Kayla Itsines are considered athletic and beautiful, while larger—and stronger—professional athletes like Serena Williams and Karyn Marshall, a prominent figure in female lifting in the US, are mocked for looking masculine. In a recent phone conversation, Marshall recalled being asked to appear on a news show at the peak of her fame in the 1980s. The host asked her to rebut the claim, made by a representative of the Ford Modeling Agency, that women who lift weights don’t look good and shouldn’t model. “To have society come down on you and say, ‘you’re too big, you’re too muscular, you’re not feminine,’ is not something you want to hear,” Marshall said, “especially when you’re an athlete. If I’d been a man, I would’ve been praised.”

This double standard has persisted since Title IX opened playing fields to women 43 years ago: Yes, the law says women can participate, but our society insists they must remain feminine while doing so—or face censure. In a culture that prizes female beauty over all else, telling women that they will be ugly, freakish, and/or undesirable if they look too athletic is a highly effective, and entirely legal, way to keep them out of the weight room and on the elliptical.

For years, I was one of those women: A recreational runner and occasional elliptical-user, who wanted “Michelle Obama triceps” but feared strength training would lead to bulk. I didn’t exercise to build muscle; I exercised so I could occasionally eat pie for breakfast without feeling guilty. I exercised to burn calories.

And then after a difficult summer before my junior year of college—surgery interrupted a summer of language study in Russia, my grandmother died after a long illness, my boyfriend cheated on me while I was away—I stumbled upon a more effective way to lose the pounds I’d picked up on an alcohol- and cookie-heavy college diet: Stop eating. I say “stumbled upon” because it wasn’t, at first, a conscious decision. Physical pain, grief, and anger had obscured my appetite. Although I must have lost 10 pounds in a month, I didn’t realize I’d lost a noticeable amount of weight until I returned to the US. When I visited my boyfriend at his home in California, I overheard his father say I looked “amazing.” A couple weeks later, a middle-aged woman beside me on a New York subway platform asked my age (22), then told me I looked 11. My female friends seemed mostly envious, asking, rhetorically, what I ate. What did I eat?

In the mornings, coffee with milk and a single apple, core and all, stretched to last a whole hour; a few crackers for lunch, maybe a square of dark chocolate, a banana; and one actual meal a day, usually with my boyfriend, who would finish whatever food I inevitably left on my plate.

Perhaps I’m in denial, but when I tell others about that period (rarely; it embarrasses me), I say I had disordered eating or borderline anorexia. It only lasted about a year and half, I never sought professional help, I bounced back relatively quickly without gaining a lot of weight (as is common to anorexics), and I didn’t suffer from body dysmorphia. That is, I knew how skinny I was at my skinniest. I was just mistaken in thinking I needed to starve myself to feel good about my body.

I didn’t run much during that time. I had exercised to burn calories—what was the point of exercising, now that I didn’t need to?

Karyn Marshall was born in Coral Gables, Fla., in 1956. When she was two, her family moved first to Yonkers, then to Bronxville, NY, where she attended high school. Although she was an active high school athlete, playing basketball, tennis, and field hockey, she told me she “didn’t really find a sport that [she] wanted to [continue] doing.” After graduation, she went on to study nursing at Columbia University.

Marshall began weightlifting in 1978, her sophomore year, at the encouragement of her weightlifting boyfriend, Tom Tarter, and his coach, Marc Chasnov. She trained with them in the basement of a YMCA in White Plains, NY, that had only recently begun admitting women. To her surprise, she fell in love with it. Her desire to compete followed swiftly from there. “I believed weightlifting to be the most challenging sport of all, requiring strength, flexibility, speed, and perfect form…I wanted to be the best in the sport I thought was the best. And I loved being strong.”

Telling women that they will be ugly, freakish, and/or undesirable is a highly effective way to keep them out of the weight room.

Since both Tarter and Chasnov were serious, competitive lifters, Marshall received the coaching and support she needed to become a serious contender in only a few months. At the time, however, there were no local or national women’s weightlifting competitions in the US or anywhere else in the world.[[1]] “It was a brand new sport [for women],” Marshall said. “That was part of the attraction.” It was also part of the challenge. Where, and against whom, would she compete?

The answer turned out to be the first place that would have her. In the spring of 1979, Marshall learned that the trials for the Empire State Games (ESG) would be held at her gym and got permission to participate. Although she won her division, the ESG refused to let her advance. The decision didn’t come as a surprise: Marshall, the only female competitor in the games, had seized at this opportunity, knowing full well they wouldn’t let her progress regardless of her performance. Marshall wasn’t angry. “It was,” as she told me, “the world we lived in.” She knew the weight room, like clubs her father belonged to in New York City, was men’s-only.

I didn’t like gyms, with their treadmills like hamster wheels, and I especially did not like weight rooms. The few times I went to one in college, I felt soft and out of place, incompetent and weak, uncomfortable and embarrassed. The machines looked like something from A Clockwork Orange. Dumbbells above 10 pounds seemed unbearably heavy. Overwhelmed, I would do a few lunges and bicep curls and leave. But, whatever, right? I mean I was a runner, not a lifter. Weightlifting seemed more vanity than sport, a waste of time, in the mind of a person who had heard or read somewhere that the benefits of cardio outweigh all else. In truth, although I didn’t realize it at the time, the gym, and especially the weight room, intimidated me. It seemed yet another boys’ club in a world full of them, a place I, at the time, thought I did not belong, a place I thought I was choosing not to inhabit.

But, like most things if you look closely, it turns out it wasn’t quite a choice so much as an internalized cultural restriction. I felt I didn’t belong because I was supposed to feel like I didn’t belong. You’ll be unattractive if you lift. Weights are for boys. Muscles aren’t sexy on girls. And so on.

The first women’s nationals were held in Waterloo, Iowa, during Marshall’s senior spring, and two years after she had been blocked from participating in the ESG. Marshall won her weight class that year and the year after. The following year, 1984, she worked to move up a weight class in order to compete against record-setting Lorna Griffin. Marshall, who was now pursuing a career as a stockbroker and analyst on Wall Street, won that, too.

Beating Griffin, however, was secondary to Marshall’s larger goal and obsession—breaking the 75-year-old record set by Katie Sandwina. She had first heard of Sandwina at the 1983 nationals when, as Marshall told me, a prominent men’s coach said something like, “Why should [female lifters] deserve any respect until one of you breaks this old circus record? None of you are even close to what she lifted.” While his comment angered Marshall, she couldn’t help but see his point: “I almost agreed with him—like, well, yeah, how could she do it that long ago and how come none of us could do it?” After doing more research on Sandwina, Marshall made it her mission in life to break her record. At the time she thought, “That’s the part I can do. I can train hard enough to break her record. That’s what my role will be to show that [women lifters] deserve respect.”

Following the 1984 competition, Marshall was only 15kg, or 33 pounds, away from her goal. By December, she was ready to make an attempt at the record. The International Weightlifting Federation (IWF) didn’t begin documenting women’s world records until 1987, so Marshall called upon national record-keeping officials as well as Guinness, the keeper of the record that had galvanized her, to witness the lift at her local gym. That day, clean-and-jerking a 288-pound load overhead, Marshall officially replaced Sandwina as the world’s strongest woman—and earned a spot, alongside a few other athletes, on Guinness’s cover.

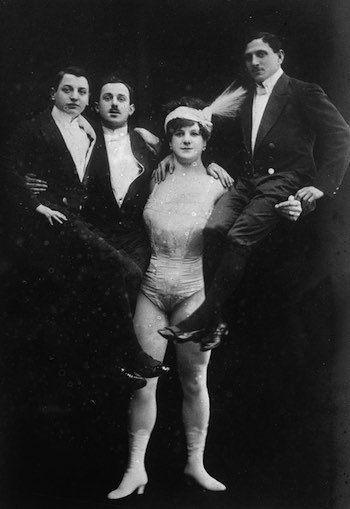

About a year later, a Guinness editor called her up. A few short months after breaking Sandwina’s record, Marshall became the first known woman to clean and jerk more than 300 pounds. They wanted to replace the photo of her lifting all that metal overhead with something more “relatable,” something that the average person could understand. Like a refrigerator. With Marshall’s input, Guinness decided to photograph her lifting the bar with a woman hanging from each end in place of the weight. The women in the photo worked at the front desk of Marshall’s gym. They are both young and pretty and petite. They do not look like they lift weights. The image echoes those taken of early 20th-century circus strongwomen, who were often asked to pose with a man, or men, instead of a barbell or dumbbell. Little had changed for female lifters. Their sport remained close to its circus roots. What’s more, in selecting such diminutive women to pose for the photograph, the Guinness officials made Marshall look, by contrast, unnaturally large, even giant-like—a freak.

Shortly after the record-breaking lift, Marshall received a call from Nippon, a Japanese television network, offering her and her husband Peter, also a weightlifter, a large sum to perform on a television special about “super people.” They flew them out first class, put them up at a Tokyo Hotel, and got an interpreter to take them around the city. “They treated me like gold,” Marshall said, “but then when [all the performers] met it was a freak show.” Other performers included the hairiest kid, the woman with the biggest breasts, the guy with the longest fingernails, the shortest man, the tallest twins—the kinds of curious attractions, which, along with the strongman and strongwoman, once drew crowds.

My bout with anorexia may have only lasted a year and a half in my early 20s, but it affected my eating habits for twice that time. I didn’t know how many calories someone of my size and age should consume per day. I still tried to quell hunger pangs with diet soda. I experimented with protein bars as meal replacements. I sometimes called a scoop of hummus and a plate of vegetables lunch. I was exercising regularly at this point—running three to four times a week and completing a single seven-minute strength circuit, ripped from the pages of the New York Times Magazine, six mornings a week—but I didn’t relearn how to eat a whole sandwich until I started weightlifting.

I started weightlifting a month before my 26th birthday with great reluctance at the urging of the man who would become my husband—a serious athlete, who had been lifting for nearly a decade as part of his training regimen. I was reluctant for a number of reasons: I didn’t want to concede I wasn’t as strong as I thought; didn’t want to “bulk up;” didn’t want to embarrass myself with general weakness/clumsiness/gym ignorance.

I didn’t relearn how to eat a whole sandwich until I started weightlifting.

After he convinced me to try it out, I kept going. I wanted to spend time with him and watch him bench-press in a muscle tank. But I wouldn’t have kept going if I hadn’t also liked it—liked the sore muscles that follow a hard workout; liked that I could track, in five-pound increments, my progress; liked that I was getting stronger. Once I’d graduated from 10-pound dumbbells, I even liked being one of few women consistently in the weight room. Lifting anything over 15 or 20 pounds felt, at least at my university rec center, like a feminist statement.

Despite all I liked about lifting, I wouldn’t have kept going to the weight room four times a week if I hadn’t also learned that I wasn’t going to bulk up. Building large muscle, much like training for any other sport, takes years of conscious, high-level training on a careful, high-protein diet, often rounded out with supplements. It’s easier for men to get big because they produce, on average, 16 times more testosterone—which promotes muscle growth—than women. Yet even with all that extra testosterone, there are few men who can gain the muscle mass they desire without turning to steroids or performance-enhancing supplements like creatine. In other words, a bulky body is not something that happens to you from lifting heavy loads; it’s something you work for. By the same token, the low weight-high rep formula recommended to “tone” women is as much a myth as the notion that Victorian women would be harmed lifting dumbbells heavier than two to four pounds (never mind that infants weigh more). The elusive “toned arm” is a muscular arm, and the only way to get it is to train with progressively heavier weights. As men do.

In 1987, Marshall qualified for the first Women’s World Championship team. In the eyes of the IWF, the championship was an experiment: The organization doubted the long-term viability of international competitions for women, given the antipathy toward female lifters in some countries.

By the time Marshall’s weight class was up to compete, the Chinese women—China turned out to be an unexpected powerhouse in female lifting—had won 16 out of 18 available gold medals. The overall placement of the US in the championship was riding on Marshall’s third and final lift, which also happened to be the last one of the entire competition. Marshall defied expectations: Not only did she win her weight class, she out-lifted every other class in the competition to reclaim the title of world’s strongest woman. The event was deemed a success and the IWF decided it would continue to organize World Championships for women.

Marshall retired from lifting in 1991, nine years before the Olympics opened weightlifting competitions to women. When I asked whether she was disappointed she had missed her Olympic window, Marshall said she had made peace with it. “We all have our role to play,” she said. “I had a tremendous opportunity to make a tremendous contribution to a sport that I love…If I was born later, I wouldn’t have had that opportunity.”

Marshall had retired from competitive lifting, in part, to focus on her career transition from Wall Street analyst to New Jersey chiropractor. In 1994, she and a partner established their own practice. She’s since become an active Crossfit competitor, placing sixth for her age group in the 2011 Crossfit Games. Although, as she noted, Crossfit incorporates a lot of lifting—clean and jerks and pull-ups and deadlifts and snatches—she no longer lifts exclusively.

In the spring of 2015, about six months after I first starting going to the gym (also, full disclosure, after I ran my first marathon), I realized my relationship to my body—for so long antagonistic and alienated—had shifted. I thought less about size and more about strength, less about form, more about function. Yet, since form and function are inextricably linked, my body looked better than it had six months ago. I’m 27 and I’m in the best shape of my life, a superlative I once thought would forever belong to my days as a varsity cross-country runner…in high school. What has made me happiest, however, is not my new body, but the fact that weightlifting had taught me to see food as fuel again, to “cheat” without anxiety or guilt, to eat.

Although the number of female lifters continues to grow, it remains low, due in large part to the same cultural myths and messages that kept people like Karyn Marshall and me out of the weight room until a man invited us in. Articles about female lifters still tend to marvel at the fact that their subject doesn’t “look like a stereotypical bulked-up weightlifter.” This kind of offhand comment both perpetuates the misconception that a woman might easily bulk up by weightlifting and reinforces gender norms by implying that she is of interest because she still looks small and stereotypically feminine. The woman who currently holds the title of “Strongest Woman in America” lives in poverty primarily because, without the slim, toned body of more famous female lifters, she can’t get corporate sponsorship, interviews, or advertising gigs.

The muscular woman challenges the cultural equation of men with strength and women with weakness. She is a threat to a social order that imagines the ideal man as a tall, muscle-bound hero in a rubber suit molded to his impressive physique. She negates the pervasive cultural myth that a woman in distress must be in want of a male hero. Indeed, if muscle is what distinguishes the hero from the non-hero, then a muscular woman can also be a hero. She can perform feats of strength on her own; she can carry the undiluted attention of a crowd; she can lift 300 pounds overhead—which, yes, is more than most men can manage.

[[1]]: The first world women’s powerlifting competition was held in 1977. Powerlifting involves the squat, deadlift, and bench press movements, whereas weightlifting includes only the snatch and the clean and jerk.