Above the Law

Mandatory minimum sentences are the product of good intentions, but good intentions do not always make good policy.

That sentence on mandatory minimum sentencing—that bugbear of criminal justice reform—isn’t from the Center for American Progress or a sentimental Nicholas Kristof op-ed. It’s from a report by the conservative Heritage Foundation, which calls harsh sentences for low-level drug offenders “the most immediate and urgent problem” facing America’s courts.

It’s a problem finally receiving attention from high places. As President Obama told a crowd at the NAACP in Philadelphia on Tuesday: “For nonviolent drug crimes, we need to lower mandatory minimum sentences or get rid of them entirely.”

The $80 billion price tag on incarcerations isn’t setting any fiscal-conservative hearts ablaze, but Republicans once saw mandatory minimums as a bulwark against jazz-and-Jerry-Garcia reefer madness. As the libertarian wing of the GOP consolidates its foothold, though, the party isn’t so rabid to take on drug offenses—some argue the libertarians have outflanked even the Democratic contenders for 2016.

Rand Paul has been particularly ebullient on the issue, and Grover Norquist, a gatekeeper to the Republican nomination, agrees: “Conservatives should lead on this.” In fact, Ted Cruz, Paul Ryan, Rick Perry, Newt Gingrich, and Jeb Bush have all joined Paul in supporting sentencing reform. (Lindsey Graham is one holdout.)

However, none of those men are president. (Yet.) For those who’ve asked if the Obama administration meant what it’s said about sentencing reform, the answer is finally, clearly, yes. Obama has actually presided over a steady stream of criminal justice reforms—with some bumps and bruises—though no announcements took so strident a tone as the most recent. The first auguries came in 2013, when Atty. Gen. Eric Holder said in a public statement—in retrospect a first salvo—that “too many Americans go to too many prisons for far too long, and for no good law enforcement reason. While the aggressive enforcement of federal criminal statutes remains necessary, we cannot simply prosecute or incarcerate our way to becoming a safer nation.”

The government followed through by dispatching with mandatory minimums for low-level offenders, and last year offered 50,000 inmates a chance to reduce their sentences. Earlier this year Obama pardoned his first inmates, and the 46 sentences commuted Monday are not expected to be the last.

It makes sense mandatory minimums are being reconsidered as marijuana legalization gains ground. Mandatory minimums were for cannabis possession: two to five years for first possession of the chronic, pursuant to the Boggs Act of 1951. In 1994, Eric Schlosser rang the warning bell, noting that minimums meant a sixth of all federal prisoners were in for marijuana offenses.

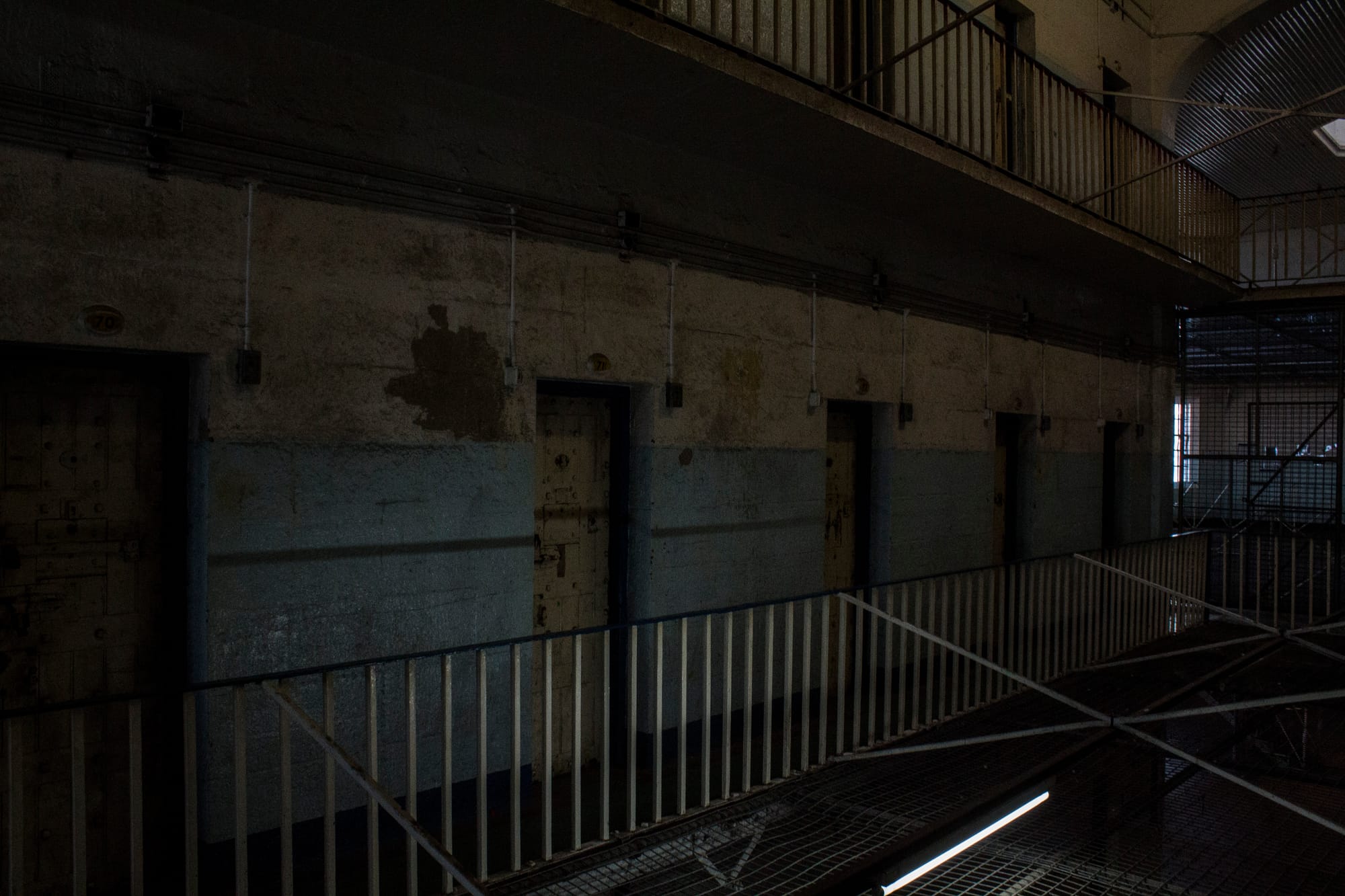

The public gravitates toward the absurd—think horror stories of lifetime incarceration thanks to seduction by hot police informant—but it’s the sheer volume of prisoners generated by mandatory minimums that will ultimately bring the system down. Today, up to a quarter of all federal prisoners face 10-year minimums for drug offenses.

On Friday, President Obama—a fan of The Wire, he has acknowledged David Simon’s show has had an effect on the way he thinks about criminal justice—suggested the mandatory minimum drama could have starred another protagonist: Himself. Like Presidents Clinton and Bush before him, Obama is known to have taken a puff—but he’s the only one of them to have done so while Black. Though mandatory minimums might, in some sense, have been expected to remove bias from the sentencing process—Ten years of jail for you! And you! And you!—results express quite the opposite: though minorities don’t use drugs any more frequently than whites, they are disproportionately handed mandatory minimums, and receive mid-sentence relief more rarely than whites. At a time when racism strikes many Americans as the most serious problem facing the US, sentencing reform offers a clear, relatively bipartisan avenue for civil rights action.

For the prisoners held down by mandatory minimums, Obama’s announcement feels like a godsend. “I am not gonna lie; I went up to my room and cried,” said one nonviolent drug offender serving life without parole. The shackles of the pardoned will literally be unloosed.

Another cohort will gain new freedom: federal judges, who will once again be asked to use their discretion to sentence low-level drug offenders. The news comes as relief to a chorus of voices who have called for sentencing reform from the bench for many years. Whose opinion better to trust than the women and men who interact with offenders on a daily basis?

Mass Incarceration: The Silence of the Judges (NY Review of Books)

On one issue—opposition to mandatory minimum laws—the federal judiciary has been consistent in its opposition and clear in its message. As stated in a September 2013 letter to Congress submitted by the Judicial Conference of the United States (the governing board of federal judges), “For sixty years, the Judicial Conference has consistently and vigorously opposed mandatory minimum sentences and has supported measures for their repeal or to ameliorate their effects.” But nowhere in the nine single-spaced pages that follow is any reference made to the evils of mass incarceration; and, indeed, most federal judges continue to be supportive of the federal sentencing guidelines.

Against His Better Judgment (Washington Post)

US District Judge Mark Bennett entered and everyone stood. He sat and then they sat.

“Another hard one,” he said, and the room fell silent. He was one of 670 federal district judges in the United States, appointed for life by a president and confirmed by the Senate, and he had taken an oath to “administer justice” in each case he heard. Now he read the sentencing documents at his bench and punched numbers into an oversize calculator. When he finally looked up, he raised his hands together in the air as if his wrists were handcuffed, and then he repeated the conclusion that had come to define so much about his career.

“My hands are tied on your sentence,” he said. “I’m sorry. This isn’t up to me.”

How many times had he issued judgments that were not his own?

Judge Regrets Harsh Human Toll of Mandatory Minimum Sentences (NPR)

Then came June 19, 1986, when the overdose of a college athlete sent the nation into shock just days after the NBA draft. Basketball star Len Bias could have been anybody’s brother or son.

Congress swiftly responded by passing tough mandatory sentences for drug crimes. Those sentences, still in place, pack federal prisons to this day. More than half of the 219,000 federal prisoners are serving time for drug offenses. “This was a different time in our history,” remembers US District Judge John Gleeson. “Crime rates were way up, there was a lot of violence that was perceived to be associated with crack at the time. People in Congress meant well. I don’t mean to suggest otherwise. But it just turns out that policy is wrong. It was wrong at the time.”

My Drug Sentences Were “Unfair and Disproportionate” (the Atlantic)

Among 500 sanctions that she handed down, “80 percent I believe were unfair and disproportionate,” she said.

Sentencing: Who Watches the Watchman (This American Life)

Terry Hatter is the Chief US District Judge for the Central District of California. He says that under the current federal guidelines, 20 percent of the time he can’t give the sentence he thinks will be fair. Judge Morris Lasker, of the Southern District of New York, a veteran of over 30 years on the bench, stopped hearing drug cases for several years. Eighty-six percent of federal judges believe the current guidelines need to be loosened.