Ah, Poor Brother

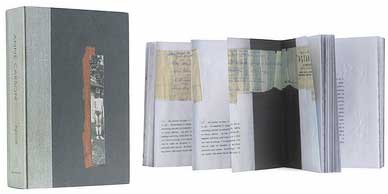

Canadian-born poet, MacArthur “Genius” Award-winner, and scholar Anne Carson—of whom Susan Sontag decreed, “She is one of the few writers writing in English that I would read anything she wrote”—offers her first book of poetry since Decreation (2006), Nox (New Directions). Though to call Nox a book is misleading—it’s an accordion fold-out in a cardboard box. And, in fact, in calling it poetry, one should also reference the pasted old letters, family photos, scribbles, anecdotes, collages, and sketches on pages that Carson interspersed with the facsimile reproductions of poems composed on the computer. As a classicist it is clear that Carson well understands the utility and potency of well-placed fragments—thus while Nox contains poetry, it stands powerfully alone as a singular object and tribute.

Nox (in Greek mythology, the primordial god of night) stands as an epitaph for Carson’s dead brother—an epitaph she created when she was translating “Poem 101 (On His Brother’s Death)” by Catullus:

Melanie Rehak has a useful take on Nox:

Carson knows, as anyone who’s lost someone they love knows, that there will be no end to the trying to make sense, no end to the sorrow and the mystery that come with death. “He refuses, he is in the stairwell, he disappears,” she offers on her final page, conjugating her loss in some deeply resonant private language that needs no translation for us to comprehend. Like someone who has died, her creation both bestows a great depth of knowledge and leaves us longing for more.