Are You Ready for Some Football?

This is the time of year when football, America’s Game, the most insidious video game of all, overtakes large parts of the country’s population, most of whom fall into the classification known as human tubers—ostensibly sentient beings almost totally unaware of what is required to play this dangerous sport, who are given to painting various body parts in their team’s colors as well as disrobing in subzero temperatures.

As I review my encyclopedic familiarity with sports books, I find it hard to bring forth even a handful of noteworthy books on football—David Megesey’sOut of Your League topping that short list with Michael Lewis’sThe Blind Side and Pete Gents’s North Dallas Forty rounding it out.

Though I can imagine Pittsburgh’s favorite daughter Holly Brubach (I’m not kidding) having written The Ones Who Hit the Hardest: The Steelers, the Cowboys, the ‘70s, and the Fight for America’s Soul (Gotham), it’s Chad Millman who does a splendid job in framing the narrative of a dying Rust Belt town—Pittsburgh versus the epicenter of new (and tainted) money Dallas through the prism of their NFL gladiators. If you followed football in the ‘70s, the dramatis personae will be familiar and the odor of hubris especially strong as you recall the advent of carnival barker Jimmy Jones America’s Team, the Dallas Cowboys.

Whether this subject requires a full-length book I leave to you, but Michael Weinreb’s study Bigger Than the Game: Bo, Boz, the Punky QB, and How the ‘80s Created the Modern Athlete (Gotham) does revisit some colorful if not dubious athlete/stars—Jim McMahon, Brian Boswoth, Len Bias, William “Refrigerator” Perry (excluding Bo Jackson, whose physical breakdown was tragic)—and once again stirs through the ashes of the celebrity/sports discussion.

* * *

In all candor, I am not sure I will have the time or inclination to read Stephen Moore’s 700-page The Novel: An Alternate History: Beginnings to 1600 (Continuum), especially considering the time frame he examines.

Thankfully a few brave and diligent readers have, with Alberto Manguel weighing in with this priceless observation:

Reading, in the deepest, most difficult, ultimately satisfying sense is, and always was, the craft of an elite, but, in spite of what demagogues and anti-intellectuals would have us believe, an elite to which almost anyone can choose to belong.

* * *

Most of the coverage and attention paid to the Mexican-U.S. border naturally deals with the various and variously perceived affronts to U.S. national sovereignty—immigration, drug trafficking, and the escalating violence attributed to both. Thus the picture of that volatile area that is brought to the rest of the U.S. is seriously distorted—certainly overwhelming the reality that this region is, in fact, another country with a vital cultural mélange fed by Mexicans and Americans, cowboys and Indians—all stripes of a vivid diversity.

(If you can track it down, Jim Harrison wrote a compelling and moving piece on the border for Men’s Journal in 2003.)

Journalist and veteran immigration reporter Tyche Hendricks has diligently investigated and explored the borderlands, and the result is her fascinating and (for the willing) eye-opening monograph, The Wind Doesn’t Need a Passport: Stories from the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands (University of California Press).

* * *

If you are a student of American history, the notion that it is a story rife with myths and, uh, how shall I put this, useful fabrications will not be a surprise.

This especially if you are aware of Howard Zinn’s groundbreaking People’s History. And even a high school-level familiarity with the American past will recognize the phrase “manifest destiny” as the imperative used, in the 19th century, to justify the “sea to shining sea” occupation and expropriation of what is now the United States.

William Pfaff’s The Irony of Manifest Destiny: The Tragedy of American Foreign Policy (Walker & Co) essentially argues that this 19th-century notion led to a distorted sense of the American mission after WWII, leading to a number of unsuccessful American military interventions.

Savvy foreign policy observer David Rieff extols:

[Pfaff’s] lucid, dismayed commentary on the follies of [American] triumphalism has been an island of reason in the imperial sea… Pfaff’s clarity and rigor at least offer posterity a way of understanding what actually happened and why the United States became both a danger to the world and to itself.

Andrew J. Bacevich (Washington Rules) echoes:

The Irony of Manifest Destiny

* * *

Princeton University mentor, historian, life-long Bob Dylan devotee, and “historian in residence” at Dylan’s official website, Sean Willentz has published an idiosyncratic, nearly 600-page study, Dylan in America (Doubleday), that he describes in this way:

Here then, are a series of takes on Dylan in America. Read them as hints and provocations, written in the spirit that holds hints, diffused clues, indirections as the most we can look forward to before returning to the work itself—to Dylan’s work and each of our own.

This, of course, allows Willentz a lot of leeway, which some reviewers were troubled by. If you are ambivalent about reading a lengthy profile, you might heed Philip Roth’s view:

All the American connections that Willentz draws to explain the appearance of Dylan’s music are fascinating, particularly at the outset, the connection to Aaron Copland. The writing is strong, the thinking is strong—the book is dense and strong everywhere you look.

One of the influences swirling around Dylan that Willentz cites is the work of various Beats—whose cultural impact is, I believe, greater than their literary contribution. In case you have assigned Kerouac, Ginsberg, Burroughs Ferlinghetti, and their cohort to the oblivion of history’s dustbin, The Typewriter Is Holy: The Complete, Uncensored History of the Beat Generation (Free Press) by Bill Morgan is an entertaining refresher to the social group and movement whom FBI director J. Edgar Hoover described as one of the three greatest threats to American security. The others being communism and intellectual “eggheads.”

Also recently published, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters (Viking) is the first collection of their correspondence commencing in 1944 up to Kerouac’s death in 1969, edited by Bill Morgan and David Stanford.

* * *

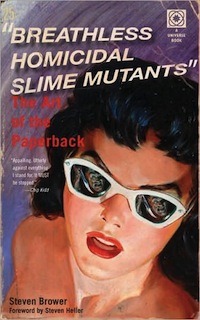

As long as I am lingering over the fertile ‘50s, consider this amusing monograp: Breathless Homicidal Slime Mutants: The Art of the Paperback (Universe), written by School of Visual Arts design mentor Steven Brower. A paean to the art of mass-market paperbacks (which were usually found in drug stores displayed on revolving wire racks), Brower quotes John Leonard’s 1968 list of the merits of mass-market paperbacks (Leonard was then editor of The New York Times Book Review):

They can be stuffed in purses, left in buses, dropped in toilets, used as coasters, eaten and thrown away. Their covers can be ripped off! Their spines can be broken! To buy a paperback today is to buy the means of revenging oneself on Western culture.

Brower points out:

Mass market paperbacks are Western culture. In many ways they are the highest form of what our culture aspires to: democratic, inclusive, utilitarian. While the hardcover and trade paperback book garner praise, reviews and awards, the lowly mass market does the heavy lifting, disseminating information, knowledge—yes, even literature—among the many.

Whether you buy that bit of laborious reasoning, the images collected here, dating back to the late 19th century, are interesting, especially the book’s cover, which features a blurb from cover designer and author Chip Kidd, “Appalling. Utterly against everything I stand for. It MUST be stopped.”

* * *

Walter Kehr is a German director and photographer whose 1995-2005 Photographs the art book publisher Kehrer-Verlag is currently offering in a limited edition of 2000. Kehr offers:

The pictures you see are from a time in my life when I was wandering and, I guess, searching like we all do at some point. Maybe because iIm human like you then perhaps you’ll see a piece of your own life. A place you’ve been, a heart you broke, someone you loved, party boys and girls or evenings you didn’t even remember—and walk with me as we all do. Bless all the souls wandering this earth.

* * *

As even occasional readers of whatever I am masticating on are aware, I am fascinated by almost all things Cuban, which explains, I suppose, naming my son Cuba and my dog after famous Cuban crooner, Beny More.

Which is why I am pleased to discover Financial Times Latin American editor John Paul Rathbone’s well-told story of the richest man in pre-Revolutionary Cuba in The Sugar King of Havana: The Rise and Fall of Julio Lobo, Cuba’s Last Tycoon (Penguin Press).

It’s a story that covers the history of Cuba in the 20th century from a singular perspective. Lobo was apparently an amazing man—even after the triumph of the revolution he was reportedly offered the Ministry of Sugar by Che. An offer Lobo turned down—of course, his properties were promptly nationalized and he left the island, never to return.

Dependable Cuba observer Ann Louise Bardach assesses:

The Sugar King of HavanaFinancial Times

* * *

Finally, I first came across Tao Lin’s name by way of what one might generously describe as some breezy and apparently non-sequitarial responses and commentary at Ed Champion’s web journal. Then he (Lin) published some stories and a novel, and I came across some reference to him by some (irritating) gossip-mongering website as the most irritating person they had dealt with. And then a mention in a New York glossy about his arrest for shoplifting.

Tao Lin’s new novel, Richard Yates (Melville House), is not exactly my cup of tea. Actually, not even close. Joshua Cohen has read Tao Lin’s writing, thought about it and him, and fashioned a cogent and readable explication far more interesting than the text it attempts to illuminate:

Ambitious, intelligent, without regret, Lin does have an acute sense for the ambiguous mood and the deadpannings of emotional truth, or what he perceives as emotional truth (though it’s closer to the millennial self-help movement known as Radical Honesty). Here are a few of the many facts strangers can learn from reading Lin’s blogs and comments on blogs: His penis measures five inches when erect, and he last had sex in December 2009; he regularly blends smoothies and is obsessed with hamsters. Fearless as Lin may be, his openness actually brings about a negation of openness; when exposure itself becomes overexposed, the effect is ruined, and what was previously shocking merely bores. Lin’s willingness to elucidate this boredom and dramatize the banal may appeal to a bored and banalized readership, but the writing itself is anything but appealing. The depleted language of Lin’s depressed books is the same depleted language of Lin’s depression, evident online.

Yeah, what he said.