Black Is Black

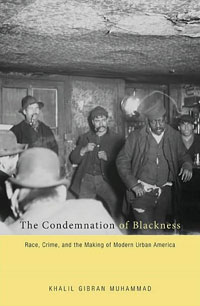

The factual platform for Khalil Gibran Muhammad’s The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America is the appalling reality that the United States “is the world’s greatest jailer.” Though this may be taken as a commendation, let me assure it is a condemnation—we have a greater prison population per capita than any other nation. Muhammad describes his study as “a biography of the idea of black criminality.”

That idea is born with the 1890 census—the first to measure the generation of African Americans born after slavery—which was tied to an array of statistics (blacks made up 30 percent of U.S. prisoners but only 12 percent of the overall population). An analysis of trends produced an undisputed conventional wisdom about black criminality that was one of the major tributaries of a huge river of racial inequity in the U.S. And, as Muhammad argues, disproportionate arrest rates and incarceration were contributory to social policy and urban planning.

The Condemnation of Blackness’s purview ends before WWII, but as the author points out, “the link between race and crime is as enduring and influential in the 21st century as it has been in the past” How else to explain blacks accounting for nearly half of the more than two million Americans in prison?

Muhammad does offer some slight glimmer of hope: “The invisible layers of racial ideology packed into the statistics, sociological theories, and the everyday stories we continue to tell about crime in modern urban America are a legacy of the past,” he writes. “The choice about which narratives we attach to the data in the future, however, is ours to make.”