Book Digest: March 19, 2007

Two of my favorite events take place, in quick succession, in March: the twice (or thrice)-yearly Bryn Mawr Bookstore half-price sale, which, incredibly, discounts some titles more and more as the week-long sale progresses; and the PEN/Hemingway Awards, which in recent years has had Russell Banks, Richard Russo, and Joyce Carol Oates as keynote speakers. This year Edward P. Jones is being featured at the PEN event held at the John Kennedy Library. Jones is also guest-editing the 2007 New Stories from The South annual anthology—both of these being good news for admirers of the good Mr. Jones.

The book sale found me acquiring and reacquiring tomes by Julio Cortazar, Susanna Moore, and Luisa Valenzuela, plus Chekov’s Sister by the vastly unheralded W.D. Wetherell and Kensington Gardens by Rodrigo Fresan, as well as some titles by Alice Munro, Thomas Bernhard, Patrick White, and Patrick Neate—for what seemed like a few shekels.

Need I remind you of Anthony Trollope’s sentiments?

Book love, my friends, is your pass to the greatest, the purest, and the most perfect pleasure that God has prepared for his creatures. It lasts when all other pleasures fade. It will support you when all other recreations are gone. It will last you until your death. It will make your hours pleasant to you as long as you live.

At least for this week.

Also, R.I.P. Natatcha Estebanez, filmmaker.

The People Look Like Flowers at Last: New Poems by Charles Bukowski

I can’t read a poem by Charles Bukowski, who died in 1994, without thinking of his splendid self-parody, The Secret of My Endurance, especially as Ecco has continued to publish his work posthumously. This volume represents the last of the five poetry collections slated to complete his ouevre—though a new selection of his later works, The Pleasures of the Damned, is forthcoming later this year. That’s some endurance, huh?

» Read an excerpt from The People Look Like Flowers at Last

Other People’s Property: A Shadow History of Hip-Hop in White America by Jason Tanz

Business writer and hip-hop enthusiast Tanz is a senior editor at Fortune Small Business; as a fan he explores the fascinating world of hip-hop and its explosion to become (arguably) America’s preeminent musical genre. Though largely anecdotal, his numerous interviews include Chuck D, MC Serch, and Fab 5 Freddy. And, it’s no surprise, there’s lots of money talk involved. The final chapter focuses on Madison Avenue’s co-optation of rap and Tanz’s disenchantment about it.

Alexis de Tocqueville: A Life by Hugh Brogan

At age 25, Tocqueville traveled to America and encountered democracy for the first time. The result of that voyage—his magnum opus, by conventional wisdom—remains the best book ever written by a European about the United States. I’d be curious to know how many Americans have read even a significant portion of the 900 pages of Democracy in America. Or who has invested in reading any of the endless stream of Tocqueville hagiographies? Personally, I think Joseph Epstein’s recent entry to the “Eminent Lives” series, Alexis de Tocqueville: Democracy’s Guide, is, at 224 pages, a lively and well-executed exercise in concision.

The Audacity of Hope: Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream by Barack Obama

I must confess I got all weepy when Barack Obama testified at the 2004 Democratic National Convention, not least because his musical introduction was a Curtis Mayfield song—music that was the soundtrack to my, uh, formative years. Apparently the buzz term the junior senator from Illinois formed—”the audacity of hope”—has become the title to his second opus. (Has anyone suggested that Obama is running for president to sell books? You read it here first.)

In any case, Obama is smart and articulate and charming, as this chat with the New Yorker’s David Remnick exhibits. As interested as I am in what smart and charming and articulate presidential candidates are like, I am not about to read their extended campaign literature. Thus, the audio CD read by the author solves my dilemma. I’m not sure that I share Senator Obama’s vision of how we can or will move beyond our divisions to tackle concrete problems, or that there exists a “radically hopeful political consensus” out there waiting for the political system to catch up. But it’s worth talking about, isn’t it?

» Read an excerpt from The Audacity of Hope

Uncouth Nation: Why Europe Dislikes America by Andrei Markovits

American scholars make a perennial exercise of trumpeting how dumb our kids are, how clueless Americans are about their global neighbors, and how much the rest of the world dislikes us. Professor Andrei Markovits argues that anti-Americanism has become a European lingua franca and that understanding the ubiquity of anti-Americanism since September 11, 2001, has a history among European elites dating back at least to July 4, 1776. Markovits also argues that this loathing has long been driven not by what America does, but by what it is. And even more troubling, he argues, this anti-Americanism has cultivated a new strain of anti-Semitism. Jonathan Yardley’s not worried, though:

Whether any of this matters very much is far from clear. Elite European anti-Americanism is more a state of mind than of policy or action. The European nations that whine most loudly about us are usually on our side in a crisis, however reluctantly at times. Heaven knows there are plenty of things about this country—not just what it does but what it is—that are fair game for criticism. But the phenomenon Markovits so tellingly describes has nothing to do with criticism. It’s just knee-jerk bloviating and deserves nobody’s attention or respect.

OK then.

» Read an excerpt from Uncouth Nation

The God of Animals by Aryn Kyle

Perhaps I am making too much of my own agnosticism, but I wish there were some convention that inhibited fiction writers from using the G-word in a title. But that’s just me. In any case, Aryn Kyle’s debut has a promising setting on a rundown horse ranch, where the Winston family’s problems require young Alice Winston to help her beleaguered father board their rich neighbor’s horses. Problems ensue. There is “devastating betrayal and a shocking, violent series of events” that test the bonds of the Winstons. So here it is—a novel without fancy restaurants, high-ticket brand names, or endless urban legend and circumambulating. Cool.

» Read an excerpt from The God of Animals

Hurricanes and Carnivals: Essays by Chicanos, Pochos, Pachucos, Mexicanos, and Expatriates edited by Lee Gutkind

Lee Gutkind, the godfather of “creative nonfiction,” assembles 15 essays by Mexican, Mexican-American, and Latin American writers that contravene the notion that creative nonfiction is solely an American domain. According to the publisher’s description:

C.M. Mayo shows us Mexico City as seen through the eyes of her pug, Picadou; Juan Villoro examines modern Mexico through the lens of demography; Homero Aridjis uses the plight of nesting sea turtles to document a slowly changing Mexican attitude toward natural resources; and Sam Quinones documents the decline of beauty-queen addiction in Mazatlán and tells us about the flower festivals where, according to lore, only two things matter: hurricanes and carnivals.

Mi gusta.

Giacomo Casanova: History of My Life translated by William Trask

Chevalier de Seingalt Giacomo, aka Casanova, who lived and thrived in the late 18th century, is a synonym for overheated amore, of which there is as much substantiated as narrated in his memoirs. Not to mention his life has served as the pretext for some wonderful novels (by Andrei Codescu and Andrew Miller) and amusing movies. In addition, Casanova was not just an energetic lover, but also a diplomat, businessman, priest in training, traveler, prisoner, magician, confidence man, gambler, professional entertainer, and charlatan. He financed business projects, organized lotteries, wrote opera libretti, and dabbled in high politics. Additionally, he rubbed shoulders with Catherine the Great, Voltaire, Louis XV, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. And, turning out more than 1,500 pages, he was considered “an autobiographer of enduring brilliance and subtlety who left behind him what is probably the most remarkable confession ever written.” Keep in mind that this Everyman edition is only a third of Casanova’s original—it’s a testament to vanity, and yet it retains the major events of his star-struck life.

Gardens in Art by Lucia Impelluso, translated by Stephen Sartarelli

Getty’s art holdings certainly allow for a wide swath of subjects to be fabricated and published, and this engaging tome is a good example. Four hundred color pictures present nearly as many works, showing and discussing the symbolic meanings embodied in gardens as well the variety of them—from small medieval enclosures to opulent royal gardens to great public parks. Assembled by architect Lucia Impelluso, this book also looks at the decorative elements of gardens, including topiaries, statues, grottoes, and labyrinths.

Back on the Fire: Essays by Gary Snyder

Of Pulitzer Prize – winning writer Gary Snyder, Jim Harrison says: “Snyder has not been subsumed by our culture but has consistently stood off to the side, giving his work a grand range far beyond academic claustrophobia.” His new anthology is decidedly autobiographical—it mixes fire, experience, and the mind, surveying the current wisdom that fires are in some cases necessary for ecosystems of the wild.

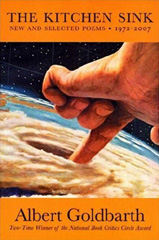

The Kitchen Sink: New And Selected Poems, 1972-2007 by Albert Goldbarth

“Will the real Shakespeare Stand Up?” is a poem by Chicago-born Albert Goldbarth, and it takes place in a bar called the Duck Blind (complete with decoys), which suggests Goldbarth’s playfulness, among other things. Given the obscurity in which poets and poetry labors (what could be more obscure than teaching at Wichita State?), Eloise Klein Healy provides some background:

Many readers probably won’t have been paying attention to the hubbub in the poetry world over the last quarter-century or so about how poetry is supposed to be written. Some poets favor the position that words don’t have to be held to their meanings, since meanings are artificial anyway. Others hold that the free-verse revolution of the 20th century has been a bust and that poets should scurry back to the sweetly predictable confines of rhythm and rhyme. Still more have been lured away to advertising and screenwriting. Then, of course, there’s Goldbarth, who has consistently gone his own way…

This is Goldbarth’s first retrospective in 14 years, which might suggest that acknowledgment of literary legislators is slow but persistent.

» Read an excerpt from The Kitchen Sink