Books About Books

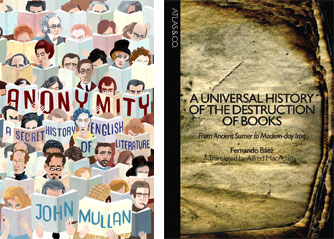

I am going to risk casting a pall of pedantry on this breezy corner of literary terrain and mention that late last millennium the term “meta” floundered onto the periphery of pop culture, even appearing in a space-filling essay in the New York Times Book Review. Apparently English majors did not fear to tread where philosophy scholars demurred. I mention this as I weighed the consideration of John Mullan’s Anonymity: A Secret History of English Literature (Princeton University Press) and Fernando Báez’s A Universal History of the Destruction of Books: From Ancient Sumer to Modern Iraq (Atlas & Co.) in the light ofwhether they were meta-books—books about books—or something else. My call is “something else,” as I see the purview of these (not too) scholarly gems as wonderful windows on human felonies and foibles associated with literary culture.

In Mullan’s case, he traces with commendable ease a host of quirky and cunning writers and their reasons for hiding their identities. From Jonathan Swift and Daniel Defoe up to Doris Lessing and George Orwell, we see the impulse for and employment of anonymity was not at all unusual. In fact, to document that commonplace custom, English bibliophiles Samuel Halkett and John Laing created four volumes of what Mullan calls “one of the great but neglected monuments to 19th century scholarship,” A Dictionary of the Anonymous and Pseudonymous Literature of Great Britain (by the time of the publication of its latest and last edition it comprised seven books and two supplementary volumes). One notion Mullan posits is worth savoring:

If we reopen once celebrated cases of anonymity, can we see how for their first readers, an uncertainty about their authorship could give new and original works of literature a special voltage?

Venezuelan scholar Báez, a worldwide authority on the history of libraries (The History of the Ancient Library of Alexandria, The Cultural Destruction of Iraq), reportedly spent 12 years rooting around dusty, dimly lit library stacks to present the dark story of smashed tablets, looted libraries, book burnings, and the heavy hand of censorship. Alberto Manguel (The Library at Night) extols: “A terrifying, masterly book from the erudite pen of Fernando Báez.”