Edward Snowden and Exploring Terra Incognita

How to read the news.

The best journalism creates understanding where the world has created questions.

When we confront the unknown, good journalism brings events, witnesses, storytellers, and an audience into a seamless line of communication, and uses those lines to re-map the knowable world.

But not all maps are created equal. If good journalism leads us out of the woods, then bad journalism can strand us in the dark with our questions. Knowing the differences between good and bad journalism can help us find better information and hold reporters accountable for their missteps. If we want better maps, we need to understand how they’re made.

In the interest of creating better news consumers, we begin where so many stories do: at the edge of what we know.

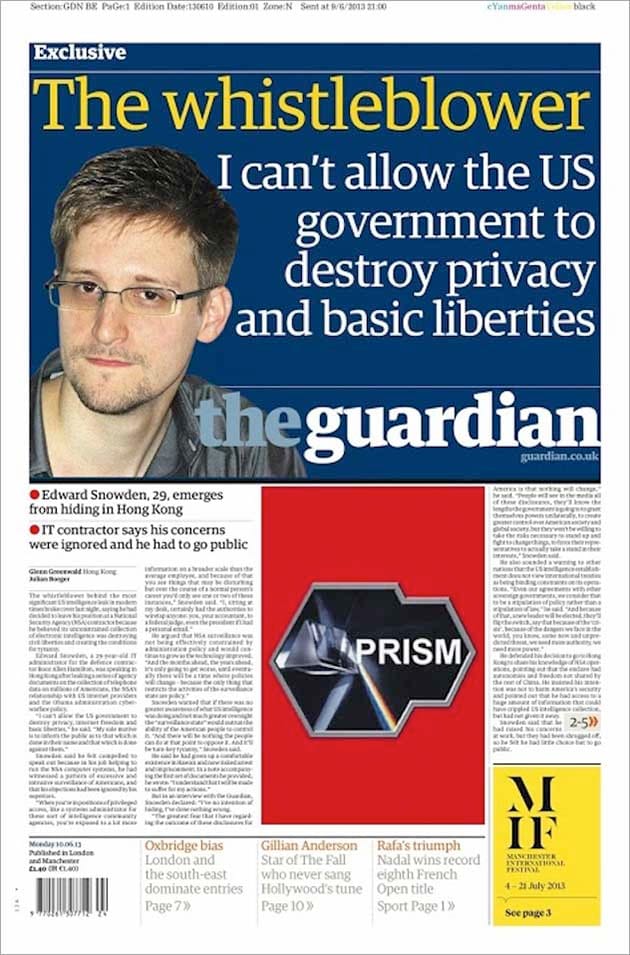

In May, the world as most of us knew it didn’t include Edward Snowden. By June, that had changed.

We learned that he calls himself Ed. We learned that he wears stubble, short hair, and glasses. And we learned that, in early June, he spent several days in Hong Kong’s Mira Hotel, where he told journalists about his decision to share details about the National Security Agency’s previously undisclosed PRISM surveillance program.

“When you’re in positions of privileged access … you’re exposed to a lot more information, on a broader scale, than the average employee,” Snowden told Glenn Greenwald, who broke the story for the Guardian. “Because of that, you see things that may be disturbing.”

Our knowledge of Snowden and Prism has grown incrementally. On June 6, the Guardian published details about an NSA surveillance project that gathered user data from companies like Facebook, Google, and Microsoft. By June 8, the New York Times had reported details of those companies’ cooperation. And on June 9, we learned the name of the man who made PRISM public. The rest—his flight to Russia and plans to seek asylum in Ecuador—followed, day by day.

In her memoir, A Field Guide to Getting Lost, Rebecca Solnit recalls a line from Plato: “How will you go about finding that thing the nature of which is unknown to you?” The reporters covering Edward Snowden and PRISM face a similar challenge. Each day they must reconcile what they knew of the world yesterday with new information. To do that, journalists and news consumers must ask themselves the same question: How do we discover what we don’t yet know?

Simply put, we look for gaps between the familiar and the unfamiliar. If we’re to leave the bulk of that work to journalists, then we should examine their stories with the same curiosity they bring to the world around us. The best reporters help us cultivate that curiosity by publishing their unanswered questions, challenging conventional wisdom or official statements, and showing us the gaps in their stories.

Take, for instance, the case of “Deep Throat,” the nickname given by a pair of Washington Post reporters to their source for much of their reporting on the Watergate scandal of the 1970s. It took decades for other journalists—and the public—to learn his real name; meanwhile, the reporters explained in their articles what little they did know about him and where the mysteries lay. The nickname was a question mark, a black box we couldn’t enter until a former FBI associate director opened the door for us.

At present, the stories of Snowden, PRISM, and the NSA are filled with such black boxes. News organizations like the Guardian and the Washington Post, which first reported Snowden’s NSA leak, have published timelines of known information about him. The same timelines, however, suggest years of Snowden’s early life that reporters still know little about, and a recent history that is doubtless more complex than we know now.

During his interview with Greenwald, Snowden said he did what he did because he was able to see patterns where other colleagues saw exceptions. “Over the course of a normal person’s career, you’d only see one or two of these instances,” he said. “When you see everything, you see them on a more frequent basis.” For reporters to see more, they must locate their blind spots, and then work to fill them in.

The same goes for readers. Eli Pariser, author of The Filter Bubble, writes about how some news companies create information silos around their audience members. “Yahoo News, the biggest news site on the Internet, is now personalized,” he said in one speech. “Different people get different things. Huffington Post, the Washington Post, the New York Times—all flirting with personalization in different ways.” News consumers, he argued, “don’t decide what gets in. And, more importantly, you don’t actually see what gets edited out.”

Consider what you have not been told about Snowden, about PRISM, about the NSA. Then make a list. How many infrastructure analysts does the NSA employ, and did they have similar access? How will Snowden’s actions affect the privacy policies of his employers? What can we learn from Snowden’s pursuit of asylum, and the national security laws that would secure his imprisonment? There are smaller questions as well. Who registered the domain name EdwardSnowden.com on June 9? Two contributions to Ron Paul’s 2012 presidential campaign appear to match Snowden’s personal history; in what other ways did he engage with politics or policy issues?

Since Snowden’s revelations, the Salt Lake Tribune has published several stories about the Utah Data Center, a $1.5 billion NSA data hub. Reporters at the paper have done a fine job of making the data center the state’s largest question mark. The site “is actually five times the size of the U.S. Capitol, stretching across 120 acres at the Utah National Guard’s Camp Williams,” writes Thomas Burr. “What goes on inside its walls—even what’s actually inside—is classified.” At Bloomberg BusinessWeek, Drake Bennett and Michael Riley scrutinized the relationship between contractors like Snowden’s former employer, Booz Allen Hamilton, and the NSA. Spokesmen declined to answer a few questions about previous NSA projects that ran significantly over-budget, but the reporters mention those unanswered questions. In doing so, Bennett and Riley draw a valuable line between what is known and what is not.

Like good reporters, we who consume news should make curiosity a habit. Without context, facts are insignificant. Information only gains gravity when we understand how it affects us. If we don’t understand—or if our usual news sources won’t responsibly guide us to an answer—then we must guide ourselves by reading more broadly, comparing divergent reports, seeking new credible sources, and putting the pieces together.

In A Field Guide to Getting Lost, Solnit writes about those mapmakers who labeled the known world alongside the unknown. “The terra incognita spaces on maps say that knowledge too is an island surrounded by oceans of the unknown,” she writes. “But whether we are on land or on water is another story.” The best journalism should place our feet on solid ground, not leave us struggling to stay afloat.