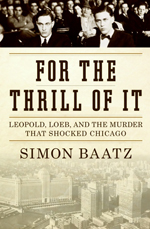

For the Thrill of It

Growing up in the shining city on the plains—Chicago—early on in my life I encountered the dark and shocking story of Leopold and Loeb’s crime: In 1924 two University of Chicago students, Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold, Jr., killed, with no apparent motive, 14-year-old Bobby Frank. One of the first novels I can remember reading was Meyer Levin’s 1956 book, Compulsion, which fictionalized, in all its lurid and perverse details, this senseless crime. Since then I occasionally think about the Leopold and Loeb case, as senseless murder and all manner of human degradation have become significant elements of what we call mainstream media. In fact, it would seem that stolen life no longer registers in the public space unless there are dramatic details as in Claus von Bülow or Orenthal J. Simpson and such. That aside, if you believe Joseph Epstein—and I do—Simon Baatz’s For the Thrill of It: Leopold, Loeb, and the Murder That Shocked Chicago ably presents this story with its stranger-than-fiction cast of characters, including the inimitable legal titan Clarence Darrow, who took on the murderers’ defense. This is a story that operates on a number of levels: legal drama, family tragedy, social history, and political chicanery. Epstein highlights one such element:

What emerges from Mr. Baatz’s account is the arrogance of medical science, and, in the case of the Freudian psychiatrists called upon, pseudo-science. The line of the Freudians was that human agency and evil intent didn’t exist. There was no need for a rigorous application of the law, they more than implied, only psychotherapy to undo the work of wretched family relations. No such thing as a bad boy, in other words, only boys who come from bad homes.

Leopold and Loeb were sentenced to 99 years in prison—a sentence that was broadcast over Chicago radio. Loeb was slashed to death in prison; Leopold was paroled in 1958 and died in 1971. As told by Baatz, their ominous story continues to reverberate.