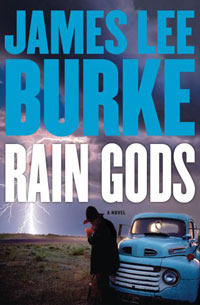

Grandmaster Burke

Texas writer James Lee Burke, author of 30 or so books (his Dave Robicheaux novels no doubt being the most well-known), and winner of two Edgar Awards for best crime novel of the year, likes to tell the story of submitting his novel The Lost Get-Back Boogie 111 times over nearly a decade. When it was finally published in 1986, it was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

His latest narrative, Rain Gods (Simon & Schuster), gives us former Korean War POW Hackberry Holland, a sheriff in a dusty southwest Texas county. Holland is tracking down the murderous nexus responsible for the massacre of nine Asian prostitutes who were unearthed with balloons of heroin in their abdomens; in the process, he tries to save a badly war-scarred Iraqi war vet and bring a sociopathic machine-gun-wielding killer to justice. To belabor the obvious, there's a lot going on. Not the least are Holland's ruminations, both personal and sociological. Here he describes images of his childhood:

...a Saturday-afternoon trip to town to watch a minor league baseball game with his father the history professor...the adjacent residential neighborhood was lined with shade trees and bungalows and 19th century white frame houses whose galleries were sunken in the middle and hung with porch wings and each afternoon at five p.m. the paperboy whizzed down the sidewalk on a bicycle and smacked the newspaper against each set of stairs with the eye of a marksman...more important than that long ago American moment was the texture of the light after a sun shower. It was gold and soft and stained with contagions of deep green of the trees and lawns. The rainbow that seemed to dip out of the sky into the ball diamond somehow confirmed one's foolish faith that both season and one's youth were eternal.

And he broadens his vision here:

Except for the television set on the wall and the refrigerated air, the scene could have been 1945. The people were the same, their fundamentalist religious views and abiding sense of patriotism unchanged, their blue collar egalitarian instincts undefined and vague and sometimes bordering on nativism but immediately recognizable as inveterately Jacksonian. It was the America of Whitman and Kerouac, of Willa Cather and Sinclair Lewis, an improbable confluence of contradictions that had become Homeric without its participants realizing their importance to the world.