It's a Mad, Mad World

The notion that insanity is the only rational response to a mad and maddening world—a notion romantically articulated by exotic psychiatric adventurer and trailblazer R.D. Laing in the euphoric phase of the Vietnam War era (“Insanity: a perfectly rational adjustment to an insane world”)—still holds some allure (at least, for me).

In a short span of time, currently calculated as a few news cycles, plugged-in Americans were yo-yoed between LeBron James’s The Decision; the fact of Gen. Stanley McChrystal’s infelicitous remarks and behavior in that herpes of all wars, Afghanistan; and an attendant brouhaha attached to freelance journalist Michael Hastings’s important reportage, Lindsay Lohan’s travails, the Bachelor and Bachelorette bickering for audience share, and yet another empty vetting of a Supreme Court nominee by various poseurs on the Senate Judiciary Committee.

How is one to make sense of this and, if one is alert, much more? No need to answer.

As previously planned in my bumbling attempt to understand the vacuous notion of “summer reading,” I am making my way through Charles McCarry’s Paul Christopher novels and finding McCarry to be every bit as riveting as in previous readings.

The Miernik Dossier, where we first encounter Paul Christopher, is assembled with memorandum, notes, phone conversations, tape transcripts, and some conventional prose narrative. It’s the late ’50s, in Geneva, where an odd grouping of intelligence operatives are paying attention to Miernik, a Polish national (suspected of being a Eastern bloc spy) whose employment with an NGO is coming to an end. There is also a Sudanese prince who intends to drive a new Cadillac—a “gift” from an American—to his father’s stronghold in East Africa with this strange crew.

Tears of Autumn, where we now understand Christopher’s history and role in The Outfit, plays out his unflagging, laser-targeted investigation into the assassination of J.F.K., and an unlikely but plausible solution of that crime and institutional resistance to Christopher’s discoveries. It is a taut, elegant picture of visible and invisible government written in transparent, unaffected prose.

The Last Supper tells in full the whole Christopher saga, beginning with the courtship of his parents, their secret transport of endangered German citizens, the fateful events that befell the Christophers as the Nazis tightened their grip on Germany, the origins of the U.S.A.’s main intelligence agency, and Paul Christopher’s attempt to save his lover from the homicidal vendetta of the vengeful Vietnamese family behind the deposed and assassinated Diem. From Germany to Massachusetts’s Berkshires, to Vietnam, Paris, and Rome, to 10 years in a Chinese prison, this story concludes with an ultimate betrayal masterfully concealed by McCarry’s elaborate plotting. More to come.

The recent Russian spy comic opera spurred a New York Times op-ed editor to call upon Charles McCarry for his expert take:

Anyway, it turned out pretty well. The Russian spies have gone back home, and four people accused of spying on Russia for the United States have been released from Russian prisons. Nobody’s mad at anybody else… If this story was the thriller it was clearly meant to be, the whole dreamed-up thing would, of course, be a joint Russian-American op to swap those four freedom fighters for those 10 fun-lovers and take the world for a ride. But fiction isn’t that strange.

* * *

My enthrallment into the world of Cold War espionage and mid-century America did not prevent me from peeking my head outside and also reading Ben Greenman’s new story collection, What He’s Poised to Do (Harper Perennial), with an enchanting Hopperesque cover. The collection continues the epistolary slant Greenman exhibited in his wonderfully designed book package Correspondences (Hotel St. George Press)—a limited-edition, handcrafted letterpress publication. What He’s Poised to Do includes six stories from Correspondences and adds 11 or 12 more.

Which reminds me that something good is up at Harper Perennial under Cal Morgan’s adventurous editorship (something akin to the excitement at Vintage Contemporaries in the ’80s as guided by Gary Fisketjon and Morgan Entrekin)—including Ben Greenman’s next literary peregrination, Celebrity Chekov. You can look forward to a freewheeling chat with Ben and myself sometime in the coming days—a conversation which will further reveal Greenman’s engaging sense of humor.

* * *

I didn’t realize that my remarks on Don Winslow’s new opus Savages (Simon & Schuster) were ahead of the book’s availability (“Why does that matter?” you may ask. Dunno.) Janet Maslin surprised me with a favorable take on Winslow’s superheated drug-and-crime extravaganza. Here’s the third graf from Ms. Maslin’s review:

Savages

Yeah, what Maslin said.

* * *

Being old enough to remember Roger Maris’s tremendous 1961 season where he battled his teammate Mickey Mantle (“Roger was as good a man and as good a ballplayer as there ever was”) for the home-run crown—breaking Ruth’s record with 61—I am glad to see Danny Peary and Tom Clavin’s much-overdue book, Roger Maris: Baseball’s Reluctant Hero (Simon & Schuster), which is also a tale about the huge destructive shift in media priorities and preferences. (In Maris’s case he was hounded and bedeviled by what was then still called “the press.”)

Peary and Clavin tell Maris’s story in fine fashion with a broad array of fresh (150) interviews, including some poignant photographs never before published.

And for those of you who are fans of Hall of Fame windbag Reggie Jackson, there is also Reggie Jackson: The Life and Thunderous Career of Baseball’s Mr. October by Dayn Perry (William Morrow). Jackson played baseball at what may be called a transformational moment in America’s former national pastime and certainly some of that is in evidence in this hagiography.

* * *

Photography, always in danger of obscured by the buzz and bloom of overbearing motion and video picture arts, is enriched and anchored in the roiling waters of our 24/7 cultural rapids by exhibitions such as “Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance, and the Camera Since 1870,” scheduled to travel from the Tate Modernto the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (Oct. 30, 2010, to April 17, 2011), then to Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, in 2011.

Here’s a description of the what you will see:

Beginning with the idea of the ‘unseen photographer’, “Exposed” presents 250 works by celebrated artists and photographers including Brassaï’s erotic Secret Paris of the 1930s images; Weegee’s iconic photograph of Marilyn Monroe; and Nick Ut’s reportage image of children escaping napalm attacks in the Vietnam War. Sex and celebrity is an important part of the exhibition, presenting photographs of Liz Taylor and Richard Burton, Paris Hilton on her way to prison and the assassination of JFK. Other renowned photographers represented in the show include Guy Bourdin, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Philip Lorca DiCorcia, Walker Evans, Robert Frank, Nan Goldin, Lee Miller, Helmut Newton and Man Ray.

And for those of you are able to attend the exhibit at its various venues, of course, there is the Yale University Press book that stands as the exhibition catalogue, with perceptive essays by the exhibit’s curator Sandra S. Phillips and additional illumination by various art history/criticism types—Simon Baker, Philip Brookman, Marta Gili, Carol Squiers, and Richard B. Woodward. As usual, Y.U.P. has produced a fine and useful complement to the live exhibition and also includes photography by Sophie Calle, Harun Farocki, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Andy Warhol, among others.

* * *

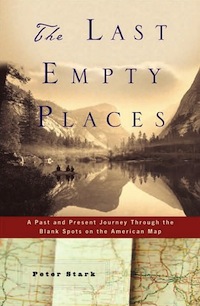

OK, I won’t (try to) be subtle—I love this kind of book. What kind of book is Peter Stark’s The Last Empty Places: A Past and Present Journey Through the Blank Spots on the American Map (Ballantine)? It is an original search and adventure story leavened by a compelling personal history—Stark grew up in a log cabin in the Wisconsin woods. Making good use of modern tools (satellite images of planet Earth), Stark sought out and traveled to four of the emptiest and untouched areas of the U.S.A.—northern Maine, central Pennsylvania, the Gila Wilderness of New Mexico, and southeast Oregon.

One reviewer has a good grasp of Stark’s accomplishment and vision:

There’s something deliciously refreshing about rambling through the United States in search of emptiness. I often find myself imagining that it, too, will be somehow overloaded. But it isn’t. The United States is a vast, mesmerizing canvas of nature, a land that in many ways is as untamed now as it was in the times of the pioneers. It’s just a matter of going in search of it.

* * *

The much admired and now lamented Southern Methodist University Press, a bastion of excellent literary publishing in its death rattle, has produced yet another noteworthy tome, namely Cynthia Phoel Morrison’s interrelated story collection Cold Snap. Set in the unlikely habitat of a ramshackle Bulgarian village entitled Old Mountain, this former Peace Corps volunteer (who spent her service in Bulgaria) weaves a narrative moving her publisher to invoke comparisons to Sherwood Anderson and Winesburg, Ohio.

Margot Livesey, as is her habit, has a useful view:

Phoel transports us to a country where jobs are scarce and men are more in love with their satellite dishes than their wives. Old Mountain is not an easy place to live, but these stories, with their surprising leaps of empathy, make it a pleasure to visit.