Jeff Bezos Sucks

Inquire of any observer within reasonable proximity of his or her wits and I doubt any would say that last week represented a hopeful moment in the life of our ailing republic. You, of course, already know the other symptoms—imperialistic hubris run amuck; “too big to fail” capitalist hyenas gorging on the U.S.A.’s economic well-being; a physical environment and habitat that we, all of us (though industry contributes 80 percent of the despoliation), are ever endangering and destroying; and then comes an incident to prove the madness that has overtaken the body politic, Mr. and Mrs. America, and all ships at sea.

I refer, of course, to L'Affaire Sherrod. I am certain that millions, trillions, countless ones and zeroes have been expended on this matter, although to be truthful I have attended to only a few. But amidst that din I was moved by Keith Olbermann’s 12-minute declamation, in which I believe he achieved his Murrow moment, as he called out that “scum” and filth purveyor Andrew Breitbart and the whole sorry lot of fools and miscreants who, by any standard of justice, would be exiled to some Devil’s Island.

Speaking of which, one of the finer points of Olbermann’s oration was his succinct representation of the infamous Dreyfus affair—wherein Captain Alfred Dreyfus, by all accounts a brilliant French artillery officer and a Jew, was court-martialed for selling secrets to the Germans, based on perjured testimony and trumped-up evidence. His sentence was to be drummed out of the military (insult) and a life imprisonment (injury) on Devil’s Island. (If you need to be refreshed on the severity of that punishment, have a look at clips from the film Papillon.) Five years later, the verdict was overturned and eventually Alfred Dreyfus was exonerated. Needless to say, this episode has befouled French history and culture ever since.

Of the recent books on the Dreyfus affair, you have the luxury of choosing from novelist (and retired attorney) Louis Begley’s concise and precise explication, Why the Dreyfus Affair Matters (Yale University Press), and Oxford historian Ruth Harris’s Dreyfus: Politics, Emotion, and the Scandal of the Century (Henry Holt), a rigorously-researched investigation, including thousands of sources previously unused, which added to her recasting the narrative with new eyes and ears, giving legitimacy to the claim for this tome as the definitive history of the whole brouhaha. Aging bad boy Christopher Hitchens weighs in:

Scrupulous and well-written… Ruth Harris’s rather beautiful and complex study is a conscious attempt to add, or better say restore, the layers of ambiguity that are lost if we accept the almost classical model of confrontation between darkness and enlightenment. It’s not that she is, in any usual sense, a revisionist. Indeed, her restatement of the essential and unarguable point—the complete innocence of Captain Alfred Dreyfus—could scarcely be bettered… In some ways, then, Harris’s narrative actually enhances the traditional picture of good triumphing over injustice, with the French secular left wearing the white hat. But she expertly identifies the exceptions… Harris is to be thanked for the care and measure of her sifting and weighing, and for the deep historical perspective that she brings to the undertaking.

* * *

That you have made it thus far in this week’s literary magic theater gives me pause to refrain from pointing out that Nobel Prize laureate William Faulkner was much more than a character in the Coen brothers’ Hollywood send-up Barton Fink.

Thus, I am pleased to pass on that the University of Virginia now houses tapesof Faulkner interacting with an audience from his 1957 and 1958 stints as the inaugural writer-in-residence at that university.

And in case you are not suffering enough guilt about the myriad ways that we are destroying nature and all that is good and right—remember the rain falls on the just and the unjust alike—reading Stan Cox’s new tome Losing Our Cool: Uncomfortable Truths About Our Air-Conditioned World is yet another act of self-flagellation.

Stay cool—need I say more?

* * *

In addition to spelling his name in a god-awful awkward manner, English ex-patriot Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) is one of the patriarchs of photography. Taking it up after a stagecoach accident and a lengthy period of recuperation, Muybridge made his reputation as a landscape photographer from his base in post-Civil War San Francisco. He is well known for his invention of the Zoopraxiscope, an apparatus he designed in 1879 to project motion pictures and his stop-motion studies.

The Corocoran Gallery of Art has recently exhibited “Helios: In a Time of Change by Eadweard Muybridge” (which travels to the Tate in London from September 8, 2010 through January 16, 2011, and to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art from February 26 through June 7, 2011).

Steidl, who publishes exquisite art and photography (even their seasonal catalogues are published in hard cover with obvious great care), offers the catalogue for the Helios exhibit with new essays by curator Philip Brookman, Marta Braun, Andy Grundberg, Corey Keller, and one of my favorite writers, Rebecca Solnit.

* * *

I don’t know if historical populizer David McCullough made palatable the idea of book-length studies of outstanding buildings and engineering feats, but his Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge (Simon & Schuster) certainly proved them commercially viable.

There have been a spate of such books recently. E.g., California historian Kevin Starr’s offering, Golden Gate: The Life and Times of America’s Greatest Bridge (Bloomsbury). Completed in 1937, as Starr makes eloquently clear, the Golden Gate serves as both an engineering marvel and a work of art. Simon Winchester gushes:

The loving and meticulous manner in which Kevin Starr has constructed this paean to one of the world’s most admired architectural icons, is everything that we have come to expect from the creator of the California Dream series, and more. This book is the ideal companion to the bridge, magisterial in authority, intimate in detail and affectionate in tone: an entirely befitting classic.

Alice Sparberg Alexiou adds to what may be the burgeoning genre of building biographies (see also Jill Jonnes’s Conquering Gotham and Gail Fenske’s The Skyscraper and the City) with The Flatiron: The New York Landmark and the Incomparable City That Arose with It (St. Martin’s Press).

Officially known as the Fuller Building, located at the intersection of Broadway, Fifth Avenue, and 23rd Street in Manhattan, the Flatiron building may not figure as much more than an interesting architectural footnote (designed by Chicagoan Daniel Burnham), but who has not beheld and been fascinated by Edward Steichen’s masterpiece image?

I guess it takes a special kind of point of view to imagine a compelling narrative for the construction of a dam. Me, I lost interest in such stories after The Ten Commandments. Perhaps there are former Soviet dam functionaries that are excited by histories such as Colossus: The Hoover Dam and the Making of the American Century by Michael Hiltzik?

OK, I jest. Pulitzer Prize-winner Hiltzik obviously has more in mind than a construction diary. (The subtitle is the tip-off. A special prize if you can name the person who the dam is named after, who was against its construction, by the way.) As his publisher claims, Hiltzik “uses the saga of the dam’s conception, design, and construction to tell the broader story of America’s efforts to come to grips with titanic social, economic, and natural forces.” Which translates to being a lucid and well-crafted scan of Great Depression-era America.

* * *

Perhaps I read somewhere that the publication of C.I.A./espionage novels was on the upswing. Or there is the possibility I thought that such a vacuous claim might be an acceptable lead sentence for what is to follow…

Ex-C.I.A. hand Barry Eislerhas both been lauded and garnered commercial success for his eight novels. Apparently he also has a righteous streak, advocating against torture and the ongoing encroachment by Big Brother on civil liberties. Inside Out (Ballantine Books) is his latest.

Susan Hasler, a 20-year veteran of the C.I.A., offers her debut with Intelligence: A Novel of the C.I.A. (Thomas Dunne Books). Patrick Anderson of the Washington Post seems to be a reliable commentator:

Hasler offers mostly despairing insights into the C.I.A.… “If there is one hard lesson I’ve learned in this town, it’s that ass-covering trumps national security every time.” “There are no policy failures, only intelligence failures”… Of course, if you think the invasion of Iraq was necessary, even wise, you’ll hate this novel. But if you think it was a tragedy brought about by top-level arrogance and deceit, you’ll probably savor Hasler’s bitter comedy. It’s a very funny book about a deeply unfunny slice of recent history. Read it and weep—but you’ll be laughing too.

Moscow Sting (Ecco) is former journalist Alex Dryden’s follow-up to his well-received debut, Red to Black, which argued that the evils of a KGB-controlled modern Russia have been hidden from us by weak-willed politicians. In this new espionage thriller, we not only have competing intelligence services but a privately owned intelligence company in play in a novel whose subtext concerns the rising threat from Vladimir Putin’s oil-rich Russia. (Aren’t we thrilled that democracy has come to the former Soviet Union? Can you wait to see what democracy looks like in post-Castro Cuba?) The storyline is simple: Anna, ex-KGB lover of a murdered MI6 maverick named Finn, tries to outfox an international gaggle of spooks to protect Finn’s secrets and their son.

I am continuing my re-acquaintance with the sublime novels of Charles McCarry this week with what I still consider his magnum opus, Shelley’s Heart (Overlook). A presidential election in the not too distant future is contested, and an oil-wealthy sheik is assassinated by his son via the complicity of the C.I.A. and the P.O.T.U.S. A secret Yale University society connected to the poet Percy Shelley lurks in the shadows of this narrative of intrigue dysfunction. Though I was amused to pick up tidbits such as the death toll of Yale graduates outstripping Harvard boys 14 to 12 in the Vietnam War, it’s McCarry’s clear-sighted provocations, such as what follows, that continue to amuse my second reading.

He soon realized that the President and his aides lived out their fifteen-hour days in fifteen-minute segments, getting through one appointment after another just for the sake of doing so, and forgetting what happened as soon as one encounter ended and another began. There was no time to think, much less reflect on the lessons of history. Decisions were made on the spur of the moment, with no regard for causes or consequences. Since boyhood Blackstone had believed that the world would be saved when at last it was ruled by wisdom. How, then, in the highest councils of the greatest nation on earth could there be no philosophical basis for policy, no inventory of national interests, no scholarship? Has this always been so in America? He suspected that the answer was yes.

And there is this dystopian appraisal of public affairs:

Senators—in fact the whole government apparatus—had long been out of the habit of living by their wits. Some had entirely lost the knack of expressing a complete thought. The prime function of the news media was to fill in blanks, so that all public figures had to do to win a front-page story with a half column of run-over, or a full minute on the evening news, was to utter a burst of language on the issue of the day that contained a strong noun and a colorful adjective. Hard-working journalists, to whom words came easily, did the rest.

The only real mystery that springs forth from my very enjoyable reading of Shelley’s Heart and the rest of McCarry’s oeuvre is why no movie has been made using these wonderful and finely crafted stories.

A real mystery.

* * *

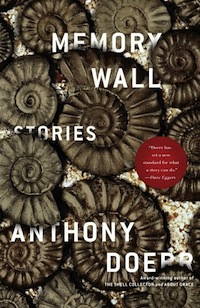

Finally, let me quickly acknowledge those of my TMN colleagues who have recently traversed the white waters of book publishing and landed their books at booksellers around the U.S.A.: Rosecrans Baldwin’s You Lost Me There (Riverhead), Anthony Doerr’s Memory Wall (Scribner), Kevin Guilfoile’s The Thousand (Knopf), and Jessica Francis Kane’s The Report (Graywolf).

More on these books to come. Congratulations and kudos.