Loss

First comes confusion. Didn’t my bike have a back wheel? Then comes anger.

First comes confusion. Didn’t my bike have a back wheel? Then comes anger. Who would steal a wheel, in broad daylight, on a bustling corner in Soho? Then comes hope. Can I see the guy who did this and catch him? (Hope is not the smartest of emotions.) Last comes Schtolenfünken. Schtolenfünken is the German word that describes the feeling of letdown and disappointment that occurs when people we think are good (cyclists) do bad things (steal my wheel), and yes, I made the word up.

But I am thinking about the characteristics of Schtolenfünken, how sad it is when those who we admire fall from our admiration—a venerable football coach failing to report a crime, a Democratic congressman tweeting photos of his penis, a Tour de France winner doping—as I carry my denuded bike over my shoulder across town to see Hal.

Hal is my mechanic. He works at Bicycle Habitat on Lafayette. Sinewy and weathered, with dreadlocks reaching to his waist, he banters with customers through a lopsided grin while fixing their bikes.

Hal thinks my Schtolenfünken theory is hopelessly naïve. Cyclists are no better than anyone else. He says whoever stole my wheel was an opportunist who sold it to a fence who sold it to a deliveryman who didn’t ask questions. Then he tells me this story:

1980, Chinatown. Hal is eating dinner with a friend at Little Sichuan. His bike is locked out front. After some hot spice eggplant, he comes outside and his bike is there but his derailleur is not. Also not there, the air in his tires. So he gets his pump and starts pumping and while he’s kneeling on the sidewalk a dog bites him in the butt. A German shepherd. As Hal bleeds, the dog’s owner says, “Don’t worry, he’s got his shots.”

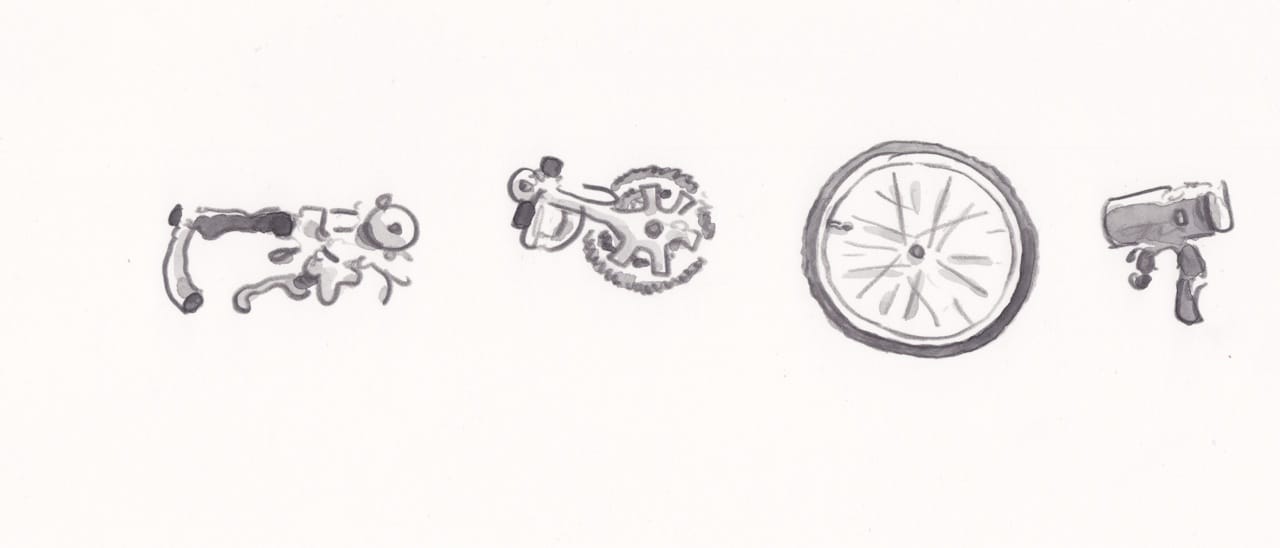

So I lose a wheel, but gain a story. And now I have a new wheel, too. As I roll home, I think of all the parts that have been stolen from my bike over the years, enough parts to build a new bike: one saddle, two wheels, one derailleur, the front brake, the back brake, the chain, four lights, a frame (stolen by rust), a bell. My bike is no longer my bike. It’s all parts. The only original part may be the lock.

I wonder where those parts are now. If they are gone, does the character of my bike remain, some soul within the bike? And what about me? The boy I was when I was 10—where are his parts? If cells replace themselves—if the heart and legs are no longer the same—what part of that boy remains? What of his worries, his daydreams? Am I still that boy?