Mad for Magazines

They are dropping like flies: Last week Kirkus and Editor & Publisher, this week ID, the venerable design magazine. As a recent TMN headline noted, over four hundred magazines closed in 2009 (including Blender, Giant, Gourmet, Portfolio, Vibe, and Metropolitan Home), which may make Forestry professionals happy, but what about the rest of us?

I feel lucky to have grown up when magazines were interesting and informative—when Life was a great weekly pictorial review, when a vast array of magazines published fiction, and when originals like The Realist, Evergreen Review, Ramparts, Scanlon’s, Avante-Garde, and Eros sprouted through the cracks in the media firmament. When Clay Felker and his small band of brothers (Milton Glaser, Edward Sorel, Richard Reeves, Walter Bernard, et al.) invented the metropolitan weekly (New York magazine), and Felker went on to revitalize Esquire. Probably that is where my love of the medium originates; it certainly wouldn’t come from catalogues like Lucky, Cargo, or InStyle.

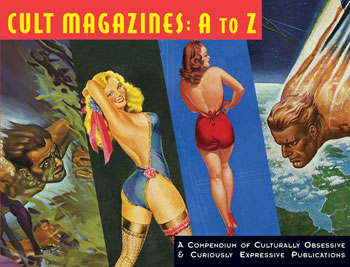

Cult Magazines A to Z: A Compendium of Culturally Obsessive & Curiously Expressive Publications, edited by Earl Kemp and Luis Ortiz (NonStop Press), is a valuable and useful addition to publishing historiography. Exploring the subcultures of mid-20th-century America, this encyclopedia comprehensively documents the huge quantity of cult magazines that thrived (throve?) beneath the mainstream. Exhibiting over 500 covers, from 1925 through 1990—we are treated an astonishing smorgasbord of publications—from the likes of Black Silk Stockings, Castle of Frankenstein, Gee-Whiz, Jaybird, Amazing Stories, boing boing, Bronze Thrills, Ballyhoo, Doctor Death, Dream World, Eyeful, Exposé, Fate, Flying Saucers From Other Worlds, Magazine of Horror, Monster Times, Phantom Detective, Humorama, Psychotronic, Search & Destroy, Satana, Red Channels, Mobster44 Times, Sexology, Spicy Stories, The Spider, The Nudist, True Thrills, Spy, Sunshine & Health, Tiger Beat, True Strange, Web Terror, Whisper, Weird Tales, and Zest. Histories and essays are included to complete the picture.

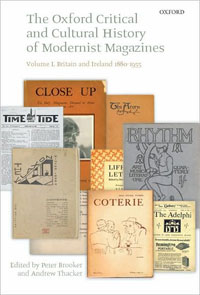

Scholars Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker, editors of The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines: Volume I: Britain and Ireland 1880-1955 (Oxford University Press) take a more academic approach—meaning less zippy full-color pictures—in the first of a projected three-volume set. Corralling over 80 magazine experts, the scope of this elephantine tome (700 pages) is what might be called western civilization (including the Irish), emphasizing what in the U.S. are called the “little magazines.”

Considering the fact that its editors are cultural studies professors (which I believe means you can scrutinize or investigate anything you want), here is OUP’s description of the History of Modernist Magazines:

…The pages of these magazines return us a world where the material constraints of costs and anxieties over censorship and declining readerships ran alongside the excitement of a new poem or manifesto. This collection therefore confirms the value of magazine culture to the field of modernist studies; it provides a rich and hitherto under-examined resource which both brings to light the debate and dialogue out of which modernism evolved and helps us recover the vitality and potential of that earlier discussion.

One almost overlooks the notion of “excitement” buried in that précis, but that is what fueled and resulted from the efforts to publish such magazines as New Age, Blast, The Egoist, The Criterion, New Writing, New Verse, and Scrutiny, as well as TheEvergreen, Coterie, The Bermondsey Book, The Mask, Welsh Review, The Modern Scot, and The Bell. And the manifold small wonders like Ploughshares, Glimmertrain, A Public Space, The Believer, The Paris Review, and the late, lamented TriQuarterly.