Manguel on Reading

To tell the truth, I find many books on reading far too precious. I mean why do I want to read about reading when I can just read?—which I have been doing with gusto most of my life (except for a brief caesura to partake in the exuberance of my post-graduate days that coincided with, well, various social revolutions and such).

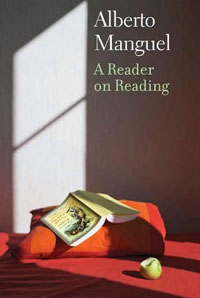

Fortunately this close-mindedness does not extend to the writing of Alberto Manguel (A Dictionary of Imaginary Places, A History of Reading, and, most recently, The Library at Night), whose books, no matter the subject, always contain much of value and stimulation. His most recent opus is a collection of nearly 40 essays, clustered into eight—for lack a more precise word—themes: A Reader on Reading (Yale University Press).

Manguel writes:

That’s an appropriate bookend to Polish Nobel laureate Wislawa Szymborska’s thoughts from her collection of prose pieces, Non-Required Reading (Harcourt):

One more comment from the heart: I am old-fashioned and think that reading books is the most glorious pastime that humankind has yet devised. Homo Ludens dances, sings, produces meaningful gestures, strikes poses, dresses up, revels and performs elaborate rituals. I don’t wish to diminish the significance of these attractions—without them human life would pass in unimaginable monotony and, possibly, dispersion and defeat. But these are group activities, above which drifts a more or less perceptible whiff of collective gymnastics. Homo Ludens with a book is free. At least as free as he’s capable of being. He himself makes up the rules of the game, which are subject only to his curiosity. He’s permitted to read intelligent books, from which he will benefit, as well as stupid ones, from which he may also learn something. He can stop before finishing one book, if he wishes, while starting another at the end and working his way back to the beginning. He may laugh in the wrong places or stop short at words that he’ll keep for a lifetime. And finally, he’s free—and no other hobby can promise this—to eavesdrop on Montaigne’s arguments or take a quick dip in the Mesozoic.