Peace, Love, Happiness

Poet Paul Guest (My Index of Horrifying Knowledge) was permanently paralyzed in a bike accident at the age of 12, which, as Mary Karr points out, “is the least interesting thing about his work.” In “User’s Guide to Physical Debilitation,” he alludes to his situation:

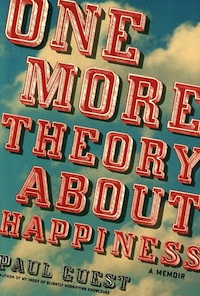

Guest’s new book, One More Theory About Happiness (Ecco), is a memoir written about his life as a quadriplegic that has been compared to the incomparable Lucy Grealey’s Autobiography of a Face. As poet Saïd Sayrafiezadeh asserts, it is “sweet and beautiful and wrenching. By so generously providing a window into his own difficult experience, Guest shows us how profoundly fragile the human body truly is, how quickly our lives can be changed forever, how much strength it takes to continue on—and most importantly, how it’s possible to create a new definition of wholeness.”

Here is an excerpt from the prologue: