Russian Haiku

Not to worry, I am not going to go crazy on this poetry thing (I don’t think). But I couldn’t get past Russian-born Vera Pavlova’s slender volume, If There Is Something to Desire: One Hundred Poems (Knopf; reportedly her first full-length volume in English), translated from the Russian by Stephen Seymour.

Reading some of these poems I am reminded that something about the Russian character or their language seems to have a pipeline to seething feelings and a dark and roiling undercurrent of emotion.

Pavlova offers this about her poetic impulse:

My first poem was a note I had written to send home from the maternity ward. I was twenty at the time, and had just given birth to Natasha, my first daughter. That was the kind of a happy experience I had never known before or after. The happiness was so unbearable that for the first time in my life I wrote a poem. I have been writing since, and I resort to writing whenever I feel unbearably happy or unbearably miserable. And since life provides me with experiences of both kinds, and with plenty of them, I have been writing for the past 26 years practically without a pause. I cannot afford staying away from writing. It could be called an addiction, but I prefer to describe it as my form of metabolism.

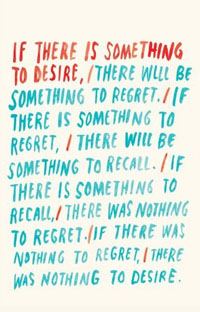

From an excerpt of If There Is Something to Desire:

Pavlova packs a lot of passion in a few spare lines, contemplating a wide stripe of everyday subjects direct and clear, aimed at the reader’s emotional center. As in these eight lines: