Summer Daze

Maybe the only thing you can depend on these days, in what was to have been our brave new world (did I miss it?), is the predictability of those benighted outlets that coalesce to form the corporate behemoth inaccurately labeled “mainstream media.” Articles on beach books or summer reading, which now are inescapably ubiquitous, used to send me frothing and foaming at the mouth; now I’m confined to a trickle of uncontrolled trickles of spittle. (My new hero is Glenn “Big Baby” Davis of the Boston Celtics; if you are paying attention to the NBA Finals—yes, finals is now capitalized—you will know why. Or contact me and I’ll explain.)

To begin with, I am not clear to what these rubrics refer—I’ve trotted out Norman Mailer’s quote on summer reading so (too) many times that I am sick of it (words to the effect, “I read all year ‘round”). In fact, I have previously written about books I have actually read at the beach, which is the only category that gives the name “beach book” sense.

Though I am still thinking you should write about beach books and summer reading in September (i.e., after the fact), I will offer some suggestions, as I am trying to look at this contrivance in a more positive frame of mind. So, my notion of summer reading is to settle on one author whose bibliography you admire and read/reread their work. Now some people set upon reading Trollope or Proust or War and Peace, which is like reading a handful of novels. But for this discussion (monologue), I narrowed my choices to Raymond Chandler, Alan Furst, Graham Greene, and Charles McCarry.

And the winner is: Charles McCarry and his seven Paul Christopher novels (this despite my animus to fiction series), though my favorite of his books is the standalone, Shelley’s Heart, which I will also reread.

* * *

Another literary/cultural phenomenon that predictably raises my hackles is the “Best Something-or-Other Writers of This-or-That” and various attendant beauty contests. To reiterate my favorite observation on this matter (from the mouth of the inestimable Will Self), “How do you win at fiction?”

My first contact with this literary bloodsport was Granta’s “Best of Young British Novelists” issue in 1983, which they’ve repeated a number of times since and eventually got around to rating (anointing, or whatever it was they were doing) American writers. Now comes the New Yorker’s version of this old chestnut. The best thing I can say about it is that at least the editors did not use the word “best” in when referring to the list of 20.

In case this kind of thing interests you (how else did you get so far in the text?), Daniel Wickett, book publisher and literary enthusiast, takes exception to the what the New Yorker has done. In an email sent to various interested parties, Wickett wrote:

New YorkerNew York Times

Stay tuned on this matter—something of interest may develop. Or not.

* * *

Bret Easton Ellis, or at least his name, exploded on the cultural scene in the ‘80s as part of a literary cadre known as The Brat Pack—though the only other writer I can recall associated with that 15 seconds is Jay McInerney. Ellis’s novel, Less Than Zero, and a well-conceived marketing campaign by young-lion editor Gary Fisketjon, put Ellis on the map, and he has managed to continue writing since then.

Now comes Imperial Bedrooms (Knopf), which revisits the characters of Less Than Zero into middle age. What’s interesting to me are Carolyn Kellog’s remarks about interviewing Ellis after having read basically the same story repeated in a number of other of Ellis’s interviews. Kellogg, being an astute and informed literary journalist for the LA Times, bemoans the difficulty in getting to the real Bret Easton Ellis. Which may or may not vex readers of the Ellis profiles, but it does raise issues about the usefulness of the contemporary interview and interviewers.

The inestimable Virginia Quarterly Review includes a brief for the written author interview, which I take to be—how shall I say?—a lot of hokum. Here’s some of that:

These days, the genre of the author interview has veered away from its verbal roots toward the written ideal championed by Maxwell. Radio and TV interviews are, of course, still verbal. And most professional journalists still conduct interviews in person or over the phone. But the rise of the blogosphere—and its generally more slack conventions—has precipitated an upsurge in e-mail interviews… It is not without its downsides.

I’ll say.

* * *

“Postmodern experimental novelist” sounds like an appellation that David Markson would use in one of his own—for lack of a better designation—novels. Markson recently passed on to—as some would say—the greater glory, and that passing was noted in a New York Times obituary that used up almost more ink than Markson received when he was alive. (OK, OK, I exaggerate to make a point.)

Any number of writers, who, of course, were his most ardent fans, championed Markson and Springer’s Progress, Wittgenstein’s Mistress, This Is Not a Novel, and his last novel, The Last Novel. He was also mentioned in literary-town-pump Alice Denham’s memoir, Sleeping with Bad Boys: A Juicy Tell-All of Literary New York in the Fifties and Sixties, as a “stud lover boy.”

Given Markson’s interest in experimentation and playing with narrative orthodoxy, he is not a writer for everyone, but, as is the case with pathfinders, he had much to contribute to the world of literature, as you can discover in this 2007 conversation:

Reader’s Block

* * *

One of the troublesome aspects of (our) beliefs—or, for some people who actually have them, so-called belief systems—is that the believer holds them to be self-evident (sound familiar?), in fact so much so that they transform to truths in the blink of an eye. For years I have believed that the history explored in Howard Zinn’s groundbreaking magnum opus was obvious—apparently, hidden in plain sight.

Zinn’s humane perspective and provocative revision, embodied in The People’s History of the United States, has seen a virtual historiographic cottage industry arise, the latest iteration of which is a History Channel documentary (and now DVD) The People Speak, featuring various declamations, speeches, and expressions of The People (if you know what I mean).

Northwestern mentor and scholar T. H. Breen’s American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People (Hill and Wang) seems to belong in the Zinn camp. But I was troubled by the lack of mention of Zinn and his work in American Insurgents, so I wrote to Professor Breen, who responded:

Although I never met him, I greatly admired Professor Zinn. Indeed, he agreed to read my book for the publisher just before it was released. Unhappily, he died a few days later and so I shall never know what he thought of the argument. But while I shared his sense of the need of a genuine history of the people, I did not specifically draw on his treatment of the period 1773-1776. For these years, I turned to his friends and supporters—Al Young and G. Nash, for example—who are thanked in the notes. Perhaps I should have said more about Zinn. We need more scholars of his persuasion just.

Breen’s monograph lifts the curtain of the American Revolution to light on the so-called grass-roots insurgency that lay the groundwork for the former. Edmund Morgan, Pulitzer prize-winning and famously failed biographer of Ronald Reagan, blurbs:

Breen has uncovered the grass roots of the American Revolution in the unheralded acts of ordinary people. Meeting in towns and villages throughout the colonies, they gave public notice that they no longer consented to British rule. Without the prompting of the leaders who have figured so largely in standard histories, they established their own independence well before Thomas Jefferson and company declared it in their famous document.

* * *

You are no doubt saying to yourself, “What’s up with Martin Heidegger?” The author of that great philosophical opacity, Being and Time, is a frequent subject in contemporary literary conversations—based in large part because he was the paramour of the great 20th-century thinker (Jewish, by the way) Hanna Arendt, and more to the point a philosopher apparently sympathetic to the National Socialism party line.

Scholar Emmanuel Faye researches this troublesome piece of intellectual history in his well-researched Heidegger: The Introduction of Nazism into Philosophy in Light of the Unpublished Seminars of 1933-1935 (Yale University Press), which includes citations from unpublished seminars to expose Heidegger’s sympathies. Elsewhere in this tome Fay presents Heidegger’s virulent anti-Semitism. All of which leads Fay to contest the notion that Heidegger’s sympathies were naïve and unconsidered.

First published in France in 2005, a newly translated (by Michael B. Smith) English edition has recently become available.

* * *

Not unusually, I have been laboring again to gain understanding of the idea of a “big book”—the kind that fills many column inches or megabytes of space in what seems an increasingly market-driven journalism. (What else can explain the regular trotting out of opening-weekend film grosses, amount of copies sold, and the idiotic fascination with other people’s incomes?)

Anyway, the big book is that product of the book-publishing world that you end up hearing about despite any efforts to opt out of the shit-stream of publicity and attendant hoopla. Whatever its literary qualities, the book seems to end up obscured by a constant din.

Currently the big book is Justin Cronin’s The Passage (Ballantine Books), which has broken into Amazon.com’s Top 10. Projected to be a trilogy and a movie, Cronin’s opus will, if the chatter and ululation is to be taken seriously, join the rarified heights occupied by Dan Brown, that Harry Potter woman, and soon the egregious, polymathic Glenn Beck.

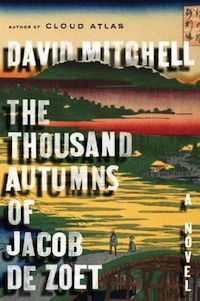

Personally, I think the big book for this moment is David Mitchell’s new novel, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet. Hallelujah!