The 49ers Stink

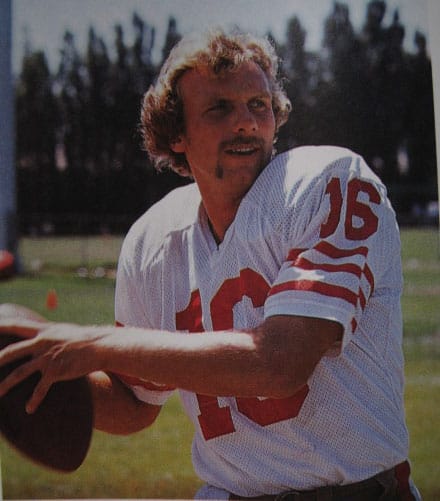

When Joe Montana took his last snap as a 49er, in the final game of the 1992 regular season, I was a quiet five-year-old living in the southernmost reaches of the Bay Area. Montana came on during the second half, after an injury-forced hiatus of nearly two full seasons.

He had been struggling with his back for years, and even after securing an impressive victory against the Lions that night, he was again sidelined during the playoffs. The 49ers, led by rising star Steve Young, would end their season with an NFC Championship loss to the Cowboys. Four months later, Montana would be traded to the Kansas City Chiefs. I don’t remember it firsthand, but the legend of Montana’s fall and Young’s rise was my first taste of the narrative sacrifices football teams make to win.

Spectacle and reality are closely intertwined in the modern NFL. Winning is more important than a good narrative. That’s why the 49ers dumped aging great Montana in favor of the sprier Young. But a win that provides a heroic narrative, one rich in plays that look better on television—like Young’s then-unprecedented runs—is more valuable than a win on points alone.

So while the quarterback controversy that today’s 49ers are flirting with pales in comparison to the tension of the Montana/Young years, there’s a hidden parallel. Erstwhile QB1 Alex Smith, unlike Montana, will be remembered as a component of, rather than the galvanizing force behind, a great team. But while it’s too early to tell what exactly hot-handed Colin Kaepernick can offer, the excitement over him, like the excitement that once centered on Young, demonstrates that fans are hungry for something more. It’s not unreasonable to assume that Kaepernick’s potential to wow in HD influenced Harbaugh’s decision to start him this Sunday against the Rams.

It’s not that the 49ers have been losing with Smith at the helm. It’s that their victories—specifically Smith’s performance during those victories—haven’t inspired a great deal of confidence. In the 49ers 34-0 pantsing of the Jets in week 4, Smith was merely “efficient,” throwing 143 yards with no touchdowns.

His numbers were much the same against the Seahawks three weeks later, a grim 13-6 victory in which Smith racked up a meager 140 passing yards. He threw for over 10 yards only twice. In the red zone, he missed an opportunity to throw first to Michael Crabtree, then to Randy Moss, for a probable touchdown, on the same down. When he did eventually pass, he was intercepted.

Smith at his best is a responsible, make-no-mistakes, manage-the-clock, run-the-ball, throw-sensible-slant-passes quarterback. He doesn’t dazzle. Which means even his better plays are rarely NFL Films material, and seeing—on a big screen, slowed down and zoomed in—is believing.

Kaepernick on the other hand—with his 40-yard catch-and-run to Manningham in the first quarter against the Saints last Sunday; with his six-play, 80-yard drive, including a 45-yard pass to Delanie Walker that opened the second half; with his 9.2 yards per attempt—passes the “eye test.” (In this highlight reel, the Manningham catch is at 00:15, and the Walker reception is at 1:37.) Even in the Jets game, it was Kaepernick who thrilled, running for a touchdown early in the second quarter.

The conversation about Alex Smith centers on what he doesn’t do: cause turnovers; throw long passes. You can’t zoom in on negative qualities. The conversation about Kaepernick, on the other hand, is visceral. For former Ravens head coach Brian Billick, it’s Kaepernick’s physical skills that astound, “his throwing action, the fluidity with the way the ball comes out of his hands, and, obviously, the athleticism.” Those are attributes that show up on instant replay.

And while head Coach Jim Harbaugh’s decision to bench Smith isn’t as obviously wrenching as George Seifert benching Montana, it’s not devoid of emotional weight. There is, first of all, some evidence that Smith might deserve the starting job: through the first 10 games of the season his quarterback rating has averaged 104.1, good for fifth in the league; he’s completed 70 percent of his passes and thrown only five interceptions.

And then there’s the relationship between Smith and Harbaugh. In his first six seasons in the NFL, the 2005 draft’s No. 1 overall pick played under six different offensive coordinators, underwent shoulder surgery, and was repeatedly benched in favor of Shaun Hill and then Troy Smith. It’s easy to craft a narrative that has Harbaugh, who was hired in 2011, believing in Smith when no one else would.

Smith certainly rewarded that belief with results, passing for over 3,000 yards for the first time in his career, throwing a league-low five interceptions, and putting up a QB rating of just over 90. In 2010, the 49ers were 6-10. The next year, Harbaugh’s first as head coach, the team made it to the NFC Conference game. With this kind of backstory, it’s possible to read a great deal of pathos into what Harbaugh allegedly told Smith before the Saints game last Sunday: “I’m going with Kaepernick. Alex, I’m sorry.”

Hearing Harbaugh hem and haw on Wednesday—he explained that “The rationale is we have two quarterbacks that we feel great about as starting quarterback,” then admitted that Kaepernick’s recent performance “tips the scales. Colin we believe has the hot hand. We’ll go with Colin,” only to seemingly backtrack, claiming “And we’ll go with Alex. They’re both our guys”—it was hard not to feel a twinge in one’s heart.

For Harbaugh too, apparently: He was recently treated for an irregular heartbeat at Stanford Hospital, and has since given up chewing tobacco and four of his five daily Diet Cokes. Good news for him; bad news for fans who enjoy his crazy eyes on the sidelines.

The stress of deciding between two quarterbacks—one a flashy crowd-pleaser, one a nice, quiet guy who’s taken a lot of knocks—may be hard on Harbaugh’s heart, but it shouldn’t be too hard on his head. If Smith’s narrative is more appealing—the disappointment who made good—and his numbers impress, Kaepernick has both the numbers and the slow-mo flair. And in a sport watched on a wide-screen, style will always win out over narrative substance.