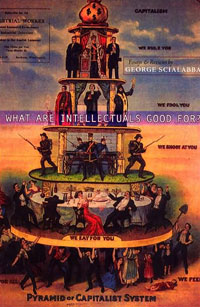

What Are Pointy Heads Good For?

It makes sense that all those pointy-headed intellectuals (a quick search of the Internet and my claim will be confirmed) would flock around George Scialabba and his new anthology of essays and reviews, What Are Intellectuals Good For? (Pressed Wafer Press). If that smallish chorus doesn’t congratulate each other, who will? Which probably explains why there seems to be no so-called major media coverage of Scialabba’s new opus (unless you count NPR, but that’s another story), no You Tube videos, and why Dan Brown and his ilk rule the bestseller lists.

NPR’s Maureen Corrigan coos:

What Are Intellectuals Good For?

Scott McLemee, who wrote the introduction, elsewhere has written:

The Divided Mind,

Though not an intellectual, I am as fond of a good story (which Scialabba’s biography is) and elegant and rigorous prose as the next fellow. And like Mr. Scialabba, I am especially fond of quotations, citations, and epigrams in what are puzzlingly (to me) entitled commonplace books. Scialabba has assembled one, which is both a small treasure chest of wit and graceful truisms and, in some way, telling about its creator.

New Yorker

From “An Interview with Edmund Wilson” (1962)

Nicely done.