-

Oct. 21, 2020

Quarterfinals

-

Toni Morrison

A Mercy

v.

The Sisters BrothersPatrick deWitt

-

Judged by

Helen Rosner

A fun little exercise for a novelist, maybe, would be to go visit the portrait wing of a museum and roll some dice, or draw slips of paper out of a hat or put on a blindfold, and spin around—the mechanism is unimportant, really, the point would be to arrive at a random selection of, let’s say, four or five paintings, and then set oneself the task of writing a character study inspired by each one, linking them all together in a shared world. I have no idea if this is actually a good idea (I am not a fiction writer!), or even if it’s an original thought—maybe this sort of gallery roulette is actually the central procedure of the first year of your average MFA program, and all those people at museums who gaze at paintings while emitting a palpable sense of purpose are actually just doing seminar homework.

I started reading Toni Morrison’s A Mercy for a second time within minutes of finishing my first read. It’s a slim novel, fast-moving, and staccato—it’s a lightweight book, not in the sense of flimsy and unprofound, but the way that an aircraft is lightweight: a considered, meticulous construction, optimized for nimbleness, rapidity, flight. “What’s that book about, that you’re reading it again?” asked one of the people I spend time with lately, and it was when I was reaching for a way to answer his question that my mind surfaced this idea of the portrait-gallery assignment. A Mercy is a novel of portraits: The chapters skip from character to character, delivering action by way of recollection, slowly sketching in the substance of secrets. (That’s why I went right back to the beginning again: Like much of Morrison’s work, A Mercy begins in a place of almost jarring opacity, but the revelations build and build until, at the end, you reach something that feels like truth. The second read is a wholly new experience—almost another book entirely.)

We study the portrait of Jacob Vaark, at first, an Anglo-Dutch trader in the American colonies in the late seventeenth century, but he’s just the grit at the center of the pearl. This is a novel about the women in Vaark’s possession—three of them enslaved, and one his wife. Through them, in turn, it is a novel about what it means to be possessed. (One of the book’s most striking moments—the brief appearance of a secondary character accused, by her histrionic religious community, of being a demon—riffs slyly on another meaning of the term. You’d never call A Mercy a funny book, but Morrison, in her structural brilliance, weaves in some ravishingly witty flourishes.) The voices of these women are radically distinct: the frozen third-person of Lina, a Lenape woman raised by European colonists and sold to Vaark as a young teenager; the feverish first-person of Florens, a Black girl on the cusp of womanhood, who directs her narration at a mysterious subject whose identity gradually becomes clear; the self-denial of Rebekka, Vaark’s wife, ordered via advertisement and delivered by ship.

The themes at play aren’t exactly subtle: Is a wife a sort of slave? Is devotion to God a sort of enslavement by choice? Is greed? Is desire? “To be given dominion over another is a hard thing; to wrest dominion over another is a wrong thing; to give dominion of yourself to another is a wicked thing,” Morrison writes. And yet one of the marvels of A Mercy is that it never quite trips over the line to straight-up allegory. The strangeness and dreaminess and nightmarishness of its narrow world feel real, and terrible, and illuminating.

The Sisters Brothers is a remarkably apposite book to consider against A Mercy: Both are, in their ways, books about the forging of America, the bone-rot of violence, the casual slaughter of Native Americans—not to mention the almost hallucinatory strangeness of inhabiting a geographic place that’s in the process of becoming itself. The brothers of the title, Eli and Charlie Sisters, are gunslinging hitmen riding from Oregon City to San Francisco at the height of the California gold rush, in order to put a bullet in a man who’s done wrong by their employer, the mysterious Commodore. The two wend their way down the Pacific Northwest in a vivid, spectacularly violent picaresque—the landscapes they traverse are oddly empty of fellow travelers, but dense with omens and corpses, many (of both) of the brothers’ own making.

Eli Sisters, our narrator, is the marginally less psychopathic of the two siblings. He’s prone to depression and existential angst, he’s drawn in sympathy to outsiders and the downtrodden. While Charlie gets trashy drunk and avails himself of the book’s steady stream of cartoonish perfumed whores, Eli falls in love with women who seem sad, whose names he never learns. He’s an appealing if slightly absurd narrator (or maybe appealing for his absurdity), delivering both his thoughts and his dialogue in a florid, circumloquacious, Coen-Brothers-antihero sort of way:

My very center was beginning to expand, as it always did before violence, a toppled pot of black ink covering the frame of my mind, its contents ceaseless, unaccountably limitless. My flesh and scalp started to ring and tingle and I became someone other than myself, or I became my second self, and this person was highly pleased to be stepping from the murk and into the living world where he might do just as he wished. I felt at once lust and disgrace and wondered, Why do I relish this reversal to animal?

The people Eli and Charlie meet on their slingshot journey are almost all similarly loquacious, almost all ready, at the moment of greeting, to unload a précis of their most recent round of Jungian analysis. Please don’t mistake this description as critique: It is a joy to read this sort of dialogue, absolutely addictive in its rhythms and syncopation. The episodic structure, too, unfolds into a surprising and deeply pleasing symmetry: What seems at the outset to be the brothers’ MacGuffin of a mission, just an excuse for us to watch them murder their way through a string of clapboard towns and the stretches of land between them, turns out to be something miraculously real. They reach their target (which is not quite the same thing as reaching their goal), and then, once various astonishing things happen, boomerang back home again, changed but also unchanged.

These books are both wonders, in their own way—I felt paralyzed, at first, about whether I would even be able to choose a winner between them. After I read A Mercy for the second time I decided to give the same to The Sisters Brothers, driven by some rigid sense of fairness, and maybe that’s where things started to unravel. Here’s a spoiler: At the end of the book, Eli brings Charlie back to their mother’s house, where she welcomes them and loves them despite their litany of fearsome sins. DeWitt’s writing is mastery, but to what end? There’s blood all over both books, but in The Sisters Brothers it’s used as house paint, an aesthetic consideration, a rollicking entertainment. A Mercy is about the blood, and the bodies it stains. Both are good. One is better.

Match Commentary

By Charlotte Scott & Andrew Womack

Andrew Womack: Charlotte, welcome to the commentary booth! Could you please introduce yourself to the readers?

Charlotte Scott: Hi Andrew! I’m a recent college graduate living in Chicago, and I’ve been following the Tournament since 2016, when I was introduced to it in a high school 21st-century literature class.

Andrew: Wait, the ToB was in a high school literature class?

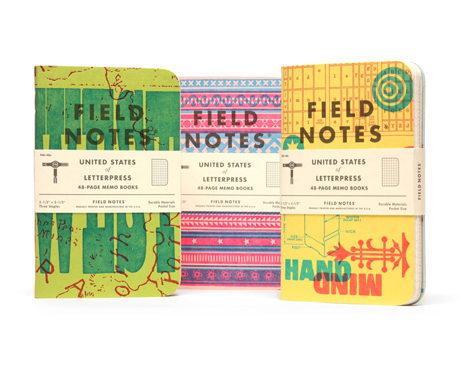

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.Charlotte: Yes! Is that how you know you’ve made it? Shoutout to Mr. Campbell, your class changed my life.

Andrew: Yes, thank you Mr. Campbell! And how would you describe yourself as a reader?

Charlotte: Since that class, I’ve been entirely devoted to contemporary literature. I love how it (and the Tournament) asks you to consider your own tastes and what you look for in a book—you can’t form an opinion based on legacy when a book is less than a year old. I went to a college with a core curriculum, so I spent a lot of time debating the merits (and definition) of the canon and reading books that are “important” but troublesome, clunky, and monolithic. Four years of that made me realize that in my free time I’d rather be unburdened by legacy and instead read books that I like! I read mostly women, don’t really care for plot, and am intrigued—but picky—about experiments in form.

Andrew: Excellent. So, what did you think about today’s judgment?

Charlotte: I have a total crush on Judge Rosner. I’ve read her writing in the New Yorker for years, and I was blown away by her Normal People versus Fleishman Is in Trouble judgment this spring. Now she’s done it again, and I feel like the only thing standing between me and my debut novel is a nice trip to a museum. Her description of A Mercy as a novel of portraits was so apt, and perfectly in sync with Judge Chancellor’s description of A Mercy as full of images. I couldn’t have described A Mercy as such before reading those judgments but they helped me put words to what I found so intriguing about its structure. However, I’m jealous of the humor everyone else, including Judges Gay and Rosner, seemed to find in the The Sisters Brothers. Did anyone else find it...not funny?

Andrew: I know the Commentariat has feelings here! It does seem to work for some readers, but not for others. Had you read both of these books prior to the Super Rooster?

Charlotte: I read both of the books for the first time this summer in preparation for the Super Rooster (I was 10 and 13 when the books came out). I was dragging my feet a bit before The Sisters Brothers for unknown reasons, and it pleasantly surprised me. I really grew fond of Eli and his devotion to his brother, his horse, and his toothbrush. But this summer, A Mercy struck me as the exact right book. I was craving a book that took seriously American violence, and in Judge Rosner’s words, “the bodies it stains,” and the answer was Toni Morrison. (The answer is usually Toni Morrison.) I know I said I didn’t care much for legacy, but to read Toni Morrison in 2020 is to remember that her work has always taken the body seriously, from lust to violence, in ways that few other authors even dare. What about you—are you loyal to either one?

Andrew: The answer is yes, however I’ve sworn myself to impartiality! OK fine, it’s A Mercy for me. What other Morrison books are you drawn to?

Charlotte: I loved Jazz, the changing narrative tones and styles. And I loved her essay collection, The Source of Self-Regard. I get so excited when my favorite novelists write nonfiction because it feels like such perfect wish fulfillment. I have always wanted to know what Toni Morrison thinks about Gertrude Stein! What a gift.

Andrew: Wonderful. Thank you, Charlotte! And with that, let’s hand it down to the Commentariat for their input! And we’ll see everyone back here tomorrow for Choire Sicha’s decision between Adam Johnson’s The Orphan Master’s Son and Paul Beatty’s The Sellout.

New Super Rooster merch is now available at the TMN Store. As a reminder, Sustaining Members receive 50 percent off everything in our store. To find out why we’re asking for your support and how you can become a Sustaining Member, please visit our Membership page. Thank you.

Welcome to the Commentariat

Population: You

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

- Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

- If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

- While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus

tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “ Dumbledore dies .” - We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.