-

Oct. 28, 2020

Zombie Round

-

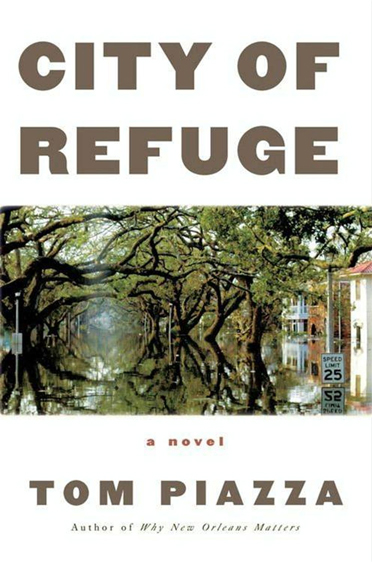

Tom Piazza

ZCity of Refuge

v.

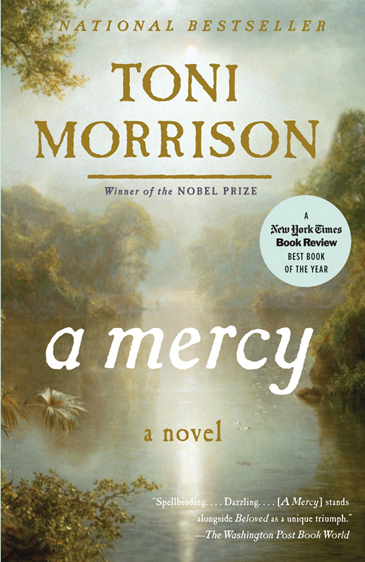

A MercyToni Morrison

-

Judged by

Merritt Tierce

I read these two books at the same time, meaning I apportioned a respective page count over a time period and read the books in small sittings, back to back. A few pages of one book, then a few pages of the other. So I was scheduled to finish reading them on the same day, but I read more than the allotment of the winner several times, breaking my quota before I realized, because I wanted to keep reading for the pleasure of it. My system for reading these books was only a function of that modern reality called “time confetti,” a situation I find lamentable and wouldn’t confess to except that it led to the unintentional discovery of a kind of empirical evidence of swept-upness. I also noticed that I usually wanted to read the winner first.

Reading City of Refuge felt like reading a talented novelist’s intricate exploration of the great catastrophe of his time and place. There’s no but, yet I know this straightforward praise somehow suggests all that isn’t enough. Enough for whom? The challenge of declaring one book better than another is, as many other ToB judges have acknowledged, the challenge of defining better. Does it mean which is more nutritious, or which tastes better? Does it mean which book is more important? For me, or the imagined collective audience? Or which book is more artistic? According to what criteria? City of Refuge would make a great limited series for television, if anyone could figure out how to shoot anything about a flood.

Both books follow people navigating a present disaster—smallpox in 1690, Hurricane Katrina in 2005—while carrying along the disasters of the past. Vietnam, addiction, poverty, rape, infanticide, slavery, abduction, exile. Being female. As such these two books are useful and resonant in a moment when we are all acknowledging the way any present disaster is amplified, compounded, by whatever unresolved disasters it lands on top of. A New York Times headline I read while writing this: “Coronavirus Limits California’s Efforts to Fight Fires With Prison Labor.” If you were wondering how to construct your great 2020 novel, you’re welcome, there are its bones. Pandemic, climate change, the carceral state of racism of capitalism, all converging to fuel an actual fire. Let the women tell the story and you could easily add exacerbated inescapable family violence, unpaid labor, and reproductive oppression into any of the above theaters of catastrophe.

This approach is, in fact, the Morrison approach. The women tell the story from underneath, and it is brutal. Lina, a native woman owned by an Anglo-Dutch trader, sums up the European invasion of North America thus:

They would come with languages that sounded like dog bark; with a childish hunger for animal fur. They would forever fence land, ship whole trees to faraway countries, take any woman for quick pleasure, ruin soil, befoul sacred places and worship a dull, unimaginative god. … Cut loose from the earth’s soul, they insisted on purchase of its soil, and like all orphans they were insatiable. It was their destiny to chew up the world and spit out a horribleness that would destroy all primary peoples.

Before I say more: There is something unfair or moot about comparing these two books, because in a sense they are chapters of the same story. It isn’t too implausible to suggest that if you sat down to write a novel about Katrina you might well ask “But where did all this start?” and find yourself in 1690—the seeds of Katrina are there. Yes, you can follow the straight line of race relations, or slavery and its cascading legacies, but the ethos of capitalism creates the disaster of Katrina as much as anything does, as the ethos of capitalism as we know it requires patriarchy and requires caste. The Anglo-Dutch trader who arrives in New England penniless, an orphan, can yet find his way within his own lifetime to wealth and the building of a completely unnecessary extra house; 400 years later, the white man in New Orleans also finds himself with an extra, salable house, and in fact, though it breaks his heart to do so, makes money off Katrina. While the Black man’s house in the Lower Ninth, expertly built with his own hands, isn’t worth anything. Take the books together and you have a complete allegory of what America is, of how race and slavery and capitalism work here, in fiction based on the actual history of real property in America. So, I will pick a winner, but these books are well read in concert.

I can also imagine a compelling screen adaptation of A Mercy, which would be eminently more shootable, as most of it would take place on a woman’s face. I’d rather watch that film than the trauma porn of Katrina, not that it would be less traumatic to see how the women are sometimes one another’s salvation and sometimes one another’s destruction and always worth less than the men, or the men’s debts, or a boy. I read these books in the year of George Floyd and the coronavirus, but it’s still, as ever, the year/age/epoch/world of the subjugated woman. So the story of the woman, even when told from her point of view, usually still revolves around a man. To which man were you given, for which man did you long, which one raped you and/or got you with child?

Piazza has a musician’s ear for the aura around a moment, and he can put words to it. As the character SJ rescues his sister Lucy from the second floor of their flooded home in the Ninth Ward, we are deep inside his experience: “There was a slight distortion, a bleed out the edges of his sense of timing, and he recognized this as a symptom of shock, and one that he could not afford.” The passages about the horrifying immediate aftermath of Katrina are haunting and effective, meaning they haven’t been easy to forget.

City of Refuge was published in 2008, before identity policing in contemporary literary fiction had reached its current zenith or nadir, or apogee, or however you want to describe wherever we are on this ride, I’m honestly not sure if we’re up or down. The white characters are boring with bourgeois concerns, but it’s OK because a white writer wrote them that way, and their boringness only sends up the exponentially more severe hardships of the Black characters. The Black characters in City of Refuge are far more engaging than the white characters. Lucy’s description of why she doesn’t want to date in midlife made me laugh out loud: “I don’t need nobody, Samuel. It alright at a distance. I get involved, it like my shit fall apart instantly. Like you carrying a grocery bag and the bottom fell out. Cans rolling all up and down the street—cabbages and shit…” But if the white writer had written a book about only the Black characters, perhaps he would have been told he shouldn’t have done that, even in 2008, and even though I would have rather read a whole book about SJ and Lucy and their world, instead of a racially balanced book half concerned with less interesting people.

Regardless, in City of Refuge the women get to die or take care of the children, no matter their race. Or they get to take care of the men, or wait for the men to make up their minds. All the City of Refuge women are good. One jokes about sex, and this means she’s cool, but by the end she’s pregnant, just like almost every other woman who ever lived to get her period. The woman who dies is an important character, but her death signals only tragedy, and gives the men something to keen about, a stage for their grief and evolution. And the tragedy in turn only signals a history beyond the scope of the book.

A Mercy at least serves the history back. “What shocked Job into humility and renewed fidelity was the message a female Job would have known and heard every minute of her life.” The Morrison women also suffer, endlessly; they also get to take care of the children and take care of the men. But I got to be with them more, and I wanted to. I wanted to know their hearts more than I wanted to know the hearts of the men in City of Refuge. And in City of Refuge the women were on the other side of the men, being considered by the men. They got their own points of view only a few times.

I’m not sure this is a valid metric, since it’s the metric of the chip on the shoulder of the hole in my female heart. But if we’re talking about the use of literature, we still need more books that make this plain: women are the original slaves, and no one will be free until Black women are free. Capitalist patriarchy is founded on the subjugation of women, and it was the practice of the subordination of women that led to the enslavement of other categories of people. The white woman in A Mercy, when she loses her white man, is meaner to the nonwhite women who depend on her, another allegorical foretelling of Where We’ll Find Ourselves Later On. As white men are losing power in America now, white women must decide whether to go down with them or do something new.

So I think it’s better to read that book, the one told by the women, whatever I mean by better, and even though I admit I have a dog in that fight. I am a dog in that fight. But that’s not why I chose A Mercy; I chose it because reading it felt more magical.

Match Commentary

By Kevin Guilfoile & John Warner

Kevin Guilfoile: Judge Tierce doesn’t say this exactly, John, but there are additional criteria in judging the Super Rooster as opposed to our annual Tournament in March. City of Refuge is a book that was pretty timely when it came out, just a few years after Katrina when the country was still feeling the aftershocks of that disaster, and it probably reads differently today. A Mercy, on the other hand, feels timeless, and perhaps has an advantage when reading both books so many years after publication.

I looked back at the final judgments in 2009, and the judges who picked City of Refuge mostly preferred it for its urgency. The lessons of Katrina still felt vitally important in the first months of Obama’s first term. Going on 12 years later, perhaps that equation has been inverted.

Nevertheless, I have a great fondness for City of Refuge. It was a book I hadn’t even heard of before I read it ahead of the 2009 Rooster, and it was a revelation to me. One of my favorite novels from that year. I was thrilled to see it make it to the finals.

John Warner: Judge Tierce’s judgment brings the word “scope” into my mind, and how different books work with different scopes, and while there is no right or wrong approach, the choice may impact how a book is read down the line. A small scope doesn’t necessarily mean a book is more perishable, nor does a big scope mean a book is somehow timeless. To pick a book at random that comes to mind on this front, is anyone interested in reading Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities? Even as an artifact of a particular era of the world of New York finance, it doesn’t strike me as interesting anymore, even though I know I lapped it up eagerly at the time.

It’s interesting to consider City of Refuge, a novel rooted in a natural disaster and a botched governmental response, in light of our current unfolding disaster and botched governmental response, how we make art out of these events. There’s a bunch of compelling nonfiction books about Katrina, but in addition to City of Refuge, I can only think of Jesmyn Ward’s Salvage the Bones (ToB 2012) as a major work of fiction. At some point, the COVID-19 novels will make their way into the world. I wonder what shape they will take, given that the experience of this disaster is so different depending on your circumstances.

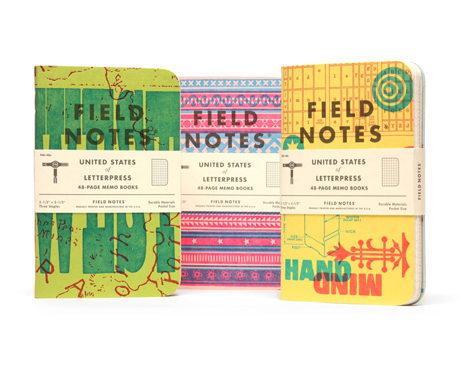

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.It also makes me wonder if we’ll start to see Covid novels before the pandemic is even “over.”

Kevin: (Salvage the Bones digression: Before the 2012 Rooster, I looked at the brackets and thought Salvage the Bones had a great shot at making it to the finals. Then it was knocked out, in what I thought was a real shocker, by Helen DeWitt’s super-weird Lightning Rods. Lightning Rods cruised all the way to the Zombies where it was eliminated by The Sisters Brothers. If I said earlier that Optic Nerve was one of the most polarizing books ever in the ToB, it’s only because I forgot about Lightning Rods. Anyway, Salvage the Bones—also great, is my point.)

Speaking of polarizing, City of Refuge was also the book that took out Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, which had smashed its way through the first two rounds, forcing you and I to invent newer and more emphatic ways to express our dislike of it. In turn, we were excoriated in the comments by Bolaño fans. I would argue, in fact, that 2009 was the year that the ToB really became the thing that it is today. That was the year the Commentariat was really born.

John: I sort of shudder to think what sort of treatment we would’ve been in for our 2666 heresy with the size and knowledge of the contemporary Commentariat. I’d like to think that we would’ve stood our ground, but we may have had to duck a few more verbal rotten vegetables.

Kevin: It says something about 2666 that you and I mention it almost every year. I still have it on my shelf. I will never read it again, nor will I recommend it to other human people, but for some reason I like having it there (it’s also a beautiful piece of book design).

On the other hand, I’m not sure where my copy of A Mercy went, and yet I recommend it all the time. It is really one of the great novels of the last 20 years. It’s “magical,” as Judge Tierce says.

John: Toni Morrison is obviously an all-time legend, but I sometimes lose sight of the true scope of her influence and impact. For a reminder (or introduction), I suggest the documentary Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am, which covers not just her own writing, but her astounding work as an editor who championed other Black writers prior to her emergence as an author. Her teaching career is just as significant, and I think it’s fair to say that she was not only a brilliant artist, but had a significant hand in creating a literary ecosystem which would make room for more writers like her.

It’s taken 50 years, my entire lifetime, to see some of the seeds that Toni Morrison planted take flower. For the first time, a Black woman, Dana Canedy, will run a major publishing house (Simon & Schuster), and we now see a critical mass of people of color as editors of imprints. This is a good thing for readers and bodes well for the Super Duper Rooster (32-book bracket, anyone?) in another 16 years time.

Kevin: You’ve just given me another idea for a callout to any Super Rooster Boosters. What are some great documentaries about novelists? I am a prolific consumer of docs, but I don’t know a lot of great documentaries about fiction writers. I don’t think I’ve even heard of the Toni Morrison one you mentioned. I can recommend the recent film about Joan Didion, The Center Will Not Hold. What are some other good ones?

John: I Am Not Your Negro on James Baldwin isn’t a straight documentary, but is a powerful piece of filmmaking. Any of the American Masters series when they cover a writer is worthwhile in my book.

Kevin: OK, tomorrow we have right-side bracket champ Normal People taking on the book it vanquished in the 2020 Championship, María Gainza’s Optic Nerve. One of my favorite contemporary writers, Victor LaValle, is in the judge’s chair, and a guest reader commentator joins our own Rosecrans Baldwin in the booth.

The next time you and I meet, John, we will have a Super Rooster champion.

New Super Rooster merch is now available at the TMN Store. As a reminder, Sustaining Members receive 50 percent off everything in our store. To find out why we’re asking for your support and how you can become a Sustaining Member, please visit our Membership page. Thank you.

Welcome to the Commentariat

Population: You

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

- Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

- If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

- While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus

tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “ Dumbledore dies .” - We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.