Although Toni Morrison’s A Mercy is historical fiction, the novel couldn’t be timelier. An aestheticized facsimile of 17th-century New England, the book reminds us that dystopia isn’t new to these shores. Apocalypses can take a long time, generations in fact, and often, their origins are hard to pinpoint, especially when one lives among people whose patriotism hinges on forgetting.

When false propaganda colonizes history books, fiction can return some scraps of truth to us. Literature can provoke our unforgetting and such a provocation is a kindness that A Mercy bestows.

Set in Maryland, a province touted as a religious refuge, Florens, an enslaved teen girl, initiates the narrative. Being the novel’s chief narrator, we can say that A Mercy is hers, and from page one she breathes with Catholic sensibility. “Confession we tell not write as I am doing now. I forget almost all of it until now. I like talk.” Absolution, which is a form of liberation, happens through speech, and Florens voices every other nonlinear chapter, creating a literary dialectic between herself and the unforgotten who enter, exit, and haunt her life.

Like Beloved, A Mercy is also a ghost story. One of its various poltergeists is Jacob Vaark, a free white farmer born in England. Adventure draws him to New England and Vaark’s visit to the plantation Jublio begets his fateful encounter with then-eight-year-old Florens.

Senhor D’Ortega, a Portuguese fop and slave trader, founded Jublio as a Catholic haven and Vaark’s contempt for him as a “Papist” and debtor yields exquisite characterization: “D’Ortega lifted an eyebrow, just one, as though on its curve an empire rested.” Vaark’s reaction to the suffering he witnesses at Jublio evokes contemporary white liberal impulses. The creditor winces at D’Ortega’s “passel of slaves,” becoming physically and spiritually ill at the sight of them, but when an enslaved woman urges, “Take her. Take my daughter,” Vaark efficiently compartmentalizes his disgust. He accepts Florens as “payment.”

Vaark understands that “lawless laws” govern New England and he honors this cruel paradox: It enriches him. After completing the financial paperwork that transfers Florens into his possession, Vaark is “eager to get away and re-nourish his good opinion of himself.” He, too, thirsts for absolution and since A Mercy takes place on 17th-century American shores, an ill-fated attempt at redemption will combine capital, violence, and the best of intentions. Vaark focuses his energies on building a garish mansion, “a profane monument to himself.” With such circular devotion, it comes as no surprise that Vaark’s offspring die one after another, seemingly cursed. While their spirits can’t be heard wailing, the dead children make their presence felt.

Over and over, the novel reminds us of place—America, London, Amsterdam, Barbados, Portugal, Africa—and time, 1690, 1691, 1692, and so forth, and Chapter I’s rootedness in 1690 presents an opportunity to contextualize A Mercy according to Mary Elliott and Jazmine Hughes. “Sometime in 1619,” they wrote for the New York Times, “a Portuguese slave ship, the São João Bautista, traveled across the Atlantic Ocean with a hull filled with human cargo: captive Africans from Angola, in southwestern Africa…”

The movement of male characters seems to advance the novel’s plot but its female characters, a minha mãe in particular, are its grist and hidden protagonists. We hear mostly from a minha mãe’s daughter, Florens, who becomes steeped in lust with a free Black man employed as Vaark’s blacksmith. “…When I see you and fall into you,” she confesses, “I know I am alive.” It is eventually revealed that Florens’s proximity to libidinal freedom is by design as it exists in contrast with the morbidness Vaark saw among those enslaved at Jublio: “The women’s eyes looked shockproof, gazing beyond place and time as though they were not actually there.”

The novel’s grimmest character is Rebekka, an Englishwoman who is Vaark’s wife. From her would-be deathbed, Rebekka campily reflects on her comparative misfortune: “So to have sailed to this clean world, this fresh and new England, marry a stout, robust man, and then, on the heels of his death, to lie festering on a perfect spring night that felt like a jest. Congratulations, Satan.” Consumed by reproductive anxiety and avarice, she, like her husband, concocts justifications: “…Jacob’s determination to rise up in the world had ceased to trouble [Rebekka]. She decided that the satisfaction of having more and more was not greed…” In the world of A Mercy, freedom erupts in staccato bursts, with those who believe they are closest to it actually being furthest, confusing dominance, desire, and distraction with liberty.

David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas bears some resemblance to A Mercy. The ridiculously ornate nonlinear novel is also preoccupied with time, place, history, the politics of confession, truth, enslavement, and freedom. It is a mansterpiece, a manument to Mitchell’s masculine literary talents that I found tedious in the sextet’s sprawl and ostentation. Yes, Cloud Atlas experiments with forms, effectively fusing many to form a mega-mega-mega-hybrid, but the cumulative effect is similar to when a rich Christmas maniac goes hog wild with trimming their tree. It’s fun to behold for a little while but I wouldn’t want that shit in my house. Let’s contrast the controlled and elegant prose about America in 1) A Mercy to the excesses of 2) Cloud Atlas so that the tree analogy pops:

- “America. Whatever the danger, how could it possibly be worse?”

- “West, the Pacific eternity. East, our denuded heroic, pernicious, enshrined, thirsty, berkserking American continent.”

As I slogged through Cloud Atlas, I found myself wishing that A Mercy had instead been paired with Parable of the Sower since what Morrison did to represent this land’s past through literature, Octavia E. Butler did for this land’s future. I especially craved this alternative when reading the third section of Cloud Atlas. In “The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish,” literary critics are characterized as those “who rea[d] quickly, arrogantly but never wisely.” We’re also described as lovers of unearned attention and a Dermot Hoggins, the author of Knuckle Sandwich, attacks Felix Finch, a reviewer for lambasting his “vainglorious” 400-page book, tossing him over the balcony: “Finch’s shriek—his life—ended in crumpled metal, twelve floors down.” The murder boosts book sales, echoing a loathsome article in the New York Times wherein escalating fascism is uncritically lauded as the publishing industry’s gravy train.

The theme strongly uniting Cloud Atlas and A Mercy is that evil requires justification. “To enslave an individual troubles your conscience,” says one of the Cloud Atlas’s fabricants, a type of enslaved clone. “To enslave a clone is no more troubling than owning the latest six-wheeler ford, ethically.” In fictional worlds, we are able to dispense with the social fictions and scripts our social order coerces us into believing and following. I praise A Mercy so highly for the complexity it achieves through brevity and because it so deftly communicates that the United States of America was a haunted house before it was ever born. Both novels render one of art’s great services: They remind us to laugh whenever anyone suggests that history is a linear march of progress.

Match Commentary

By Jason Perdue & Andrew Womack

Andrew Womack: Jason, welcome to the commentary booth! Thanks for joining us today. Let’s start with you introducing yourself to the readers.

Jason Perdue: Hi Andrew. Thank you for having me in the booth for this first semifinal matchup. Writing in from perpetually on-fire Northern California. Current status: Not Evacuated. I have been following the ToB since its inception in 2005. How I discovered it pre-social media is a mystery to me.

Out of curiosity, I searched my emails and found one from January 2006, asking if there was going to be a Year Two and to please release the titles earlier than in YEAR ONE! I cannot tell you how excited I’ve been for this Super Rooster.

Andrew: What’d we say? Were we cagey?

Jason: Not cagey. By the time I asked, you were already well into the planning and told me we’d have about six weeks between brackets release and day one. Although, you did rightfully ignore me a week later when I suggested books for the Tournament.

Andrew: Oh no—very very very belated apologies! Thank you for sticking with us—and right from the start, no less.

Jason: It’s full circle getting to do commentary on Cloud Atlas after this many years. My story (2005–2020) is its own barely connected series of abruptly changing narratives starting as a financial advisor until the recession to directing a documentary film festival for eight years to corporate tech conference production only to be laid off in March when COVID killed the events industry to now back in college finishing that English degree. The through-line this whole time has been my fandom of the Tournament of Books:

The smoke-obscured silver lining of seven months of sheltering-in-place-while-unemployed is that I’ve read more books than any other time in my life, including Parable of the Sower twice. My reading is probably best described as divining the ToB shortlist via Book Twitter and the ToB Goodreads group <waving from the booth>. While Judge Gurba bristled at the description, I could be credibly described as one of those “who read quickly, arrogantly but never wisely.”

Andrew: Then let’s make that Parable of the Sower connection right away. What would you have thought of a matchup between that and A Mercy?

Jason: Judge Gurba is wishing the two books were more in conversation about our present moment, and is there another book that speaks to this moment more than Parable of the Sower? Morrison and Butler are both talking about this unraveling American experiment. Morrison’s vivid history illustrates the creation of a society based on the exploitation and extermination of people and resources, all to erect meaningless monuments to vanity while Butler is showing us the inevitable future that results from 400-plus years of this exploitation. A prophetic novel coming to life right before our eyes would be a hard book to beat in a head-to-head competition. But, as all ToB fans know, we don’t always get the matchup we want.

Andrew: So which of our two competitors today were you rooting for?

Jason: Since it originally competed in the ToB, Cloud Atlas has held a place in my memory as an epic masterpiece that I have often said is one of my all-time favorites. So precious a spot in my mind it’s held that I have refused to watch the movie because, well, why subject myself to that disappointment? The details of A Mercy I had mostly forgotten, but I remember being very moved when I listened to Toni Morrison read it on CD back in 2009. In preparation for my inning in the commentary booth, I flipped it and read A Mercy and listened to Cloud Atlas.

Before I began, I was sure that Cloud Atlas would be the winner and chose it as such in our ToB Goodreads group bracket contest after correctly picking these books into the semifinal.

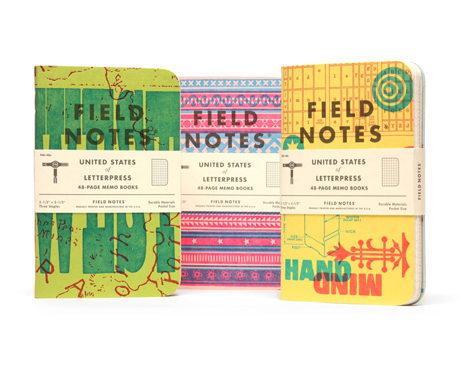

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.Listening to the incredible audiobook of Cloud Atlas, the genre characteristics of each story really come alive, and now I see how it could work as a movie or six! And, again, I was swept away by Mitchell’s virtuosity in switching voices, language, narrative styles. That disoriented feeling as the new story begins while the previous one is still buzzing in my head. Mitchell created a literary fiction horse filled with genre fiction soldiers and snuck it into my snobby lit-fic castle. But, after listening down through the nesting, it started to feel indulgent on the way back out and I lost the momentum and didn’t finish it.

After rereading A Mercy I knew that my bracket was surely busted. Morrison’s multiple voices are just as impressive as Mitchell’s. She is helping me to remember an unacknowledged history that is not just untaught but is intentionally and institutionally suppressed. “When false propaganda colonizes history books, fiction can return some scraps of truth to us.” Thank God for fiction.

Have you been rereading any/all of these books?

Andrew: Not all the books in play, but over the past few years I’ve reread these, and they remain some of my favorites. Though looking back at the 2009 championship match, I’m surprised I originally voted for City of Refuge; 11 years later, its opponent is the one that sticks with me. Something I’ve been struck by—both personally and in the book’s opening round and quarterfinal matches—is how little the magic of Cloud Atlas’s structure has faded. And I like how, in today’s match, Judge Gurba finds those structural resemblances between these two books.

What did you think about today’s judgment and the outcome?

Jason: When I read the close of Judge Gurba’s first paragraph, “Apocalypses can take a long time, generations in fact, and often, their origins are hard to pinpoint,” I thought she was referencing the scope of Cloud Atlas’s millenia-spanning apocalypse. But when it finished, “especially when one lives among people whose patriotism hinges on forgetting,” I knew she was talking about the “origins” of our currently unfolding apocalypse rooted in slavery, genocide, and capitalism.

Judge Gurba did not come to play. And she was not coy by trying to make us believe that Cloud Atlas had any chance of pulling this out. Extending our thin sports metaphor, A Mercy dominated the time of possession. Or, if you prefer baseball, Toni Morrison threw a one-hit shutout.

Andrew: “No sports metaphors” is in our judging guidelines, but go on.

Jason: When she closes with “the United States of America was a haunted house before it was ever born,” I saw A Mercy as an origin story of this country and the empty house a monument to capitalist excess.

Cloud Atlas is one of the most impressive displays of genre and historical ventriloquism, but it loses the gravitas battle in 2020. A Mercy has a lot more to say about our current moment. Because of how the fireworks of Cloud Atlas stick in the mind, I’m sure this result will be a surprise to many ToB fans and the Commentariat, but how can anyone be mad about Toni Morrison representing the first half of the ToB? In hindsight, how was it not obvious?

Andrew: So I’m wondering: As a longtime Rooster follower, do you have an all-time favorite ToB?

Jason: The Zombie comeback years were probably my favorites: 2012 (The Sisters Brothers) and 2014 (A Visit From the Goon Squad). The gut punch when the book you’re rooting for loses and the hope when it gets a second chance is always exciting.

Of the remaining books, do you think any of the potential Zombies have a chance to sneak into the final?

Andrew: Hahha, I won’t give anything away! But at least to catch everyone up: After today’s outcome, A Mercy will face its 2009 runner-up, City of Refuge, in Wednesday’s Zombie Round. And then depending on which book wins tomorrow—The Orphan Master’s Son or Normal People—it’ll mean either The Orphan Master’s Son is up against The Fault in Our Stars or Normal People once again tangles with Optic Nerve (in a rematch of our March 2020 championship).

Jason: For a non-winner to catapult over 15 winners to make it into the championship would be some kinda nuts. I had The Plot Against America doing this in my bracket, but since we’re saying goodbye to Cloud Atlas, it’s not to be.

Thanks to you and Rosecrans and everyone that’s kept this thing alive. What’s the plan for 2036?

Andrew: We’re doing the whole thing on Quibi. Just inked the deal!

Thank you, Jason, for joining us today! Everyone: Come back tomorrow for the conclusion of the semifinals, when Nicole Chung decides between The Orphan Master’s Son and Normal People.

New Super Rooster merch is now available at the TMN Store. As a reminder, Sustaining Members receive 50 percent off everything in our store. To find out why we’re asking for your support and how you can become a Sustaining Member, please visit our Membership page. Thank you.

Welcome to the Commentariat

Population: You

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

- Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

- If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

- While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus

tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “ Dumbledore dies .” - We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.