-

Oct. 20, 2020

Quarterfinals

-

David Mitchell

Cloud Atlas

v.

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar WaoJunot Díaz

-

Judged by

Jess Zimmerman

I have never forgiven The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao for “35 triple-Ds.”

I recall little else from my first reading of the novel, more than a decade ago. Had it already won the Pulitzer, the National Book Critics Circle Award, and the Rooster? Or did I just know that it was a novel everyone was talking about, that it centered on a Dominican immigrant community in New Jersey (new to me! Interesting!), and that the eponymous Oscar was a fat awkward nerd (not new! Relatable!). I don’t remember. But I do remember my increasing frustration with the primary narrator Yunior, Oscar’s Boswell and the relentless voice of the book—his shallowness, his posturing, and especially his casual negligence. In particular, one character’s stupefyingly large breasts are not once but twice described as “35 triple-Ds,” a bra size that a) does not exist and b) would be big but not, like, supernaturally big if it did. “The breasts of Luba,” he calls them elsewhere. Pal, Luba easily wears a J cup, minimum. Have you ever even talked to a woman? Have you listened?

At the time, I was probably mostly irritated at what I perceived as carelessness. But on reread, this seemingly trivial detail helps to decode my sense, which I felt even then, that The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao either has not considered me as a reader or actively does not want me there. If women aren’t looking, why not just say whatever numbers you think are big titty numbers? Who will know?

I understand that the bra error could be an intentional character note—that Yunior is the kind of person who would describe a woman’s (his girlfriend’s mother’s!) breasts in terms of her bra size, and also the kind who does not know how bras work. I know I’m supposed to assume that this kind of three-dimensional literary chess is happening here. But god, why do I want to spend hundreds of pages with that guy? (I frankly also do not want to spend hundreds of pages with Oscar, who has a proto-incel’s overinvested romanticism and a hugely affected Smart Guy vocabulary, but I’m additionally irritated on his behalf that he’s stuck with a chronicler who disdains us both—Yunior’s feelings about Oscar’s fat body are even more poisonous than his feelings about girls.) Even in 2007, if I wanted to hear about this guy’s contempt for me and everyone I know, I had myriad other options that didn’t cut into my leisure time. Now, they’re inescapable.

I understand why people praise Oscar Wao. It’s voicey, though in a way I find labored. As eager as he is to come off as a ladies’ man, Yunior rattles off facile sci-fi references with the machine gun speed of Demi Adejuyigbe’s rejected theme song from Ready Player One. The novel is unabashedly uninterested in making reading easy for people who don’t speak Spanish, which I respect—and which was especially noteworthy in the 2000s, when ideas of literary quality were more strongly whitewashed. It offers a thorough, if self-consciously breezy, account of a dictator’s psyche, which makes it an even more interesting read in 2020 than it was in 2007; look to terroristic Dominican ruler Rafael Trujillo, elaborately footnoted throughout, for a sense of the role Trump wants. It makes a gesture at investigating the demands of masculinity rather than simply enacting them, though success would depend on being able to laboriously translate Yunior’s callousness and antipathy into anxious self-protection, and thus for me it does not succeed. The parts narrated by Lola, Oscar’s sister and Yunior’s girlfriend, are a balm, a small window into what this book would feel like if it took women seriously as a concept. But ultimately, this is the story of a lonely dork getting life advice like “no-pussy is bad. But dead is like no-pussy times ten” from an insecure, annoying bro until he ultimately makes a meaningless sacrifice, and I feel like I am allergic to it and it is allergic to me. It does not want me as a reader. Fine, book, you win.

Cloud Atlas, on the other hand… well, if Cloud Atlas is anything, it is expansive. Many of its mouthpieces are as bad as Yunior or worse, but they are guides rather than interpreters—beads on a long chain of narrators that runs from the 19th century to the post-apocalypse. It is breathtakingly ambitious, an experiment not only in voice but in genre; the story is at various times a historical diary, an epistolary novel, a thriller, a picaresque, and two sci-fi books in different periods and formats. Its central characters are a hypochondriac notary, a louche musical prodigy, a courageous journalist, a shitty old man, a cloned fast-food worker, and a post-apocalyptic adolescent—and then a cloned fast-food worker, shitty old man, courageous journalist, musical prodigy, and hypochondriac notary again, because the book has the structure of a ziggurat. So help me, I love this stuff.

Does David Mitchell’s reach exceed his grasp? You bet it does. The structure is frustrating by design, cutting each story off at a climactic moment and then getting you so caught up in the next partial story that by the time the needle swings back around, you might have forgotten the characters or the stakes. The post-apocalyptic section is a Riddley Walker knockoff—in fact, many of the individual sections are derivative, and none would stand on their own. The book says its own name too many times, in a wink-nudgy way that reminds me of the Upright Citizens Brigade “titular line” sketch. There’s an inconsistent reincarnation theme—a birthmark that appears on most, but not all, of the central characters—that doesn’t account for the fact that many of these characters are, from the perspective of other characters, fictional. Adam Ewing is a real person in the world of Robert Frobisher who is a real person in the world of Luisa Rey who is a fictional person in the world of Timothy Cavendish who is a fictional person in the world of Sonmi~451 who is a real person in the world of Zachry… So how exactly is Luisa, a character in a book read by a character in a movie that Sonmi~451 watches, also a past life of Sonmi~451?

But these are nitpicks, and Cloud Atlas transcends. Its concerns are global. It aims for something more than the sum of its parts—and what it’s aiming for is a sense of human interconnectedness, of responsibility to each other and to the future. By the end, when notary Adam Ewing pledges himself to abolitionism, the book makes its intentions clear in a way that could come off smarmy and yet, after what you’ve just been through with six main characters over six centuries, feels emotionally true: “If we believe leaders must be just, violence muzzled, power accountable & the riches of the Earth & its Oceans shared equitably, such a world will come to pass,” Ewing writes. “I am not deceived. It is the hardest of worlds to make real.” But it is worth working for.

Full disclosure: My judgment was always going to turn out this way, from the moment I got my books assigned. Even if I’d been surprised by Oscar Wao on reread—and I was ready to be, I wanted to feel like a fool for not having appreciated it—it would take a lot to dethrone Cloud Atlas in my personal pantheon. This was a foregone conclusion before Oscar Wao was even published, from the moment I finished reading Cloud Atlas in 2004. I love a weird, over-ambitious sliding puzzle of a novel—it’s kind of my whole deal. But what keeps me loving Cloud Atlas more than 15 years later, when I can see the cracks and the dust shoved under the rug, is that by the time I get to the end I feel like it’s welcoming me in, like it loves me back. Life’s too short for books that despise you.

Match Commentary

By Kevin Guilfoile & John Warner

John Warner: I shouldn’t be surprised by how interesting and enjoyable it is to view past Tournaments and judgments in hindsight, but I’m just fascinated not only to see how the Super Rooster is unfolding, but how the original Tournaments would have been altered with a different judge on a particular matchup. If Jess Zimmerman had judged Oscar Wao back in 2008, in its opening-round matchup against Laura Lippman’s What the Dead Know, it seems likely that the ultimate champ would’ve been out in its first match and never come close to its runaway win over Tom McCarthy’s Remainder in the finals.

Instead, today we get Cloud Atlas moving on, looking like a real contender for the Super Rooster title.

Kevin Guilfoile: I initially read Cloud Atlas when I was a judge in the very first Tournament of Books 16 years ago. I just went back and read my judgment for the finals and was surprised to discover that, although I voted in favor of it over another book I love, Philip Roth’s increasingly relevant The Plot Against America, I hadn’t yet claimed to be a Cloud Atlas fanboy. That has happened on subsequent rereads, Cloud Atlas being one of just a few books that I go back to every few years for pleasure. It’s just a monster of a book.

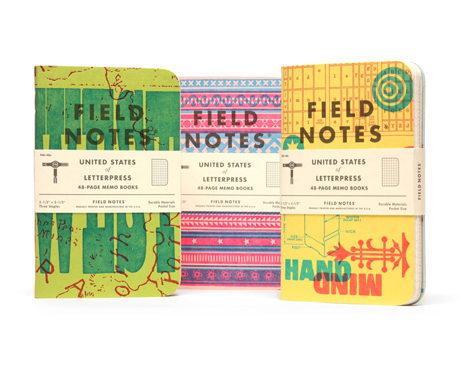

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.Judge Zimmerman does a fine job of enumerating the novel’s faults, of course. Mitchell’s books occasionally feel sloppy, but as a reader you tell yourself that it can’t be, because so much of his plotting seems so carefully constructed and this confounds you as a reader and at some point that confoundedness becomes part of his writing’s appeal. Or at least it does for me.

The process of enjoying a novel is not one where you list a book’s pros and cons as you read, and when you turn the last page you consult the tally and if there are more items on the pro side, you declare the book “liked.” Your enjoyment happens on an intuitive level, and you only make the pros and cons list when you must defend your liking or disliking, as Judge Zimmerman does here. And when you do that, you also discover that you forgive all the flaws in the books that you like, and you prosecute the flaws in the novels you don’t. I liked the way Judge Zimmerman lays that bare here. “I understand that the bra error could be an intentional character note,” she says. That was how I took it when I read it for the first time. (I’ll also confess that I do not understand the first thing about bra sizes and find men who reference them at all, or who claim to be able to convert breast volume to bra size in their head, deeply disconcerting.) But I liked Oscar Wao when I read it and so I was giving it the benefit of the doubt that Judge Zimmerman could not.

John: Since you brought up Philip Roth, I am obligated to remind the world that I am the owner of Philip Roth’s old clock radio, no fooling. I’m looking forward to next year’s release of Blake Bailey’s biography of Roth, upon which I will immediately go to the index and search the entries for “clock radio,” so I can better understand the role it played in Roth’s creative output.

Speaking of hindsight and tallying of faults, my thoughts on Cloud Atlas have been complicated in the intervening years, and through consuming David Mitchell’s subsequent efforts. Reading Cloud Atlas for the first time overwhelmed my critical sensibilities. It is so stuffed with stuff that you sort of have no choice but to give yourself over, and once that happens, it’s a pretty powerful experience as you and Judge Zimmerman articulate.

As you say, we’re willing to convince ourselves that whatever flaws may be apparent, they must be intentional because so much of the rest of it has just such a stunning effect. But I’m somewhat less willing to give Mitchell this slack as we sit here today.

As I said in the 2015 Tournament commentary, The Bone Clocks had a chapter that I found so confoundingly bad and hokey, I stopped reading the book, never to finish. It literally shot me out of the book for good. We discussed some rationales for what Mitchell was trying to do, but none of it mattered, I was done. I have not reread Cloud Atlas, but I wonder how I would see it today. Part of why I don’t reread it is because I still want to feel good about recommending the book (as I do often), so people can have the same experience I had the first time around.

But I am now wary of Mitchell. His 2020 book Utopia Avenue, an exploration of British Invasion rock, deeply intrigued me, but a couple reviews that caused concern that I may have a similar episode of spontaneous rejection, has made me hesitant to dive into the text.

Still, Mitchell is a writer who I’ll always want to know what he’s up to.

Kevin: We had the exact same reaction to that chapter of The Bone Clocks (warning to anyone clicking through to that commentary link, it is spoilery), although I was more willing than you to pretend that it didn’t happen. The rest of that novel is so good, I suppose I was willing to forgive anything. But it did feel like it must when your child is arrested for swindling pensioners and you continue to love him.

That commentary also features (courtesy of you) what I think might be the first public suggestion that there one day might be a Super Rooster. Prophetic!

Come back tomorrow when Toni Morrison’s A Mercy meets Patrick deWitt’s The Sisters Brothers with Helen Rosner passing judgment.

New Super Rooster merch is now available at the TMN Store. As a reminder, Sustaining Members receive 50 percent off everything in our store. To find out why we’re asking for your support and how you can become a Sustaining Member, please visit our Membership page. Thank you.

Welcome to the Commentariat

Population: You

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

- Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

- If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

- While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus

tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “ Dumbledore dies .” - We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.