-

Oct. 9, 2020

Opening Round

-

Cormac McCarthy

The Road

v.

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar WaoJunot Díaz

-

Judged by

Carolyn Kellogg

When The Road and Oscar Wao won their respective Roosters, I was thrilled. Longtime genius Cormac McCarthy was finally recognized. Junot Díaz had struggled for years to complete a novel, and then it became a beloved bestseller and a prizewinner. But a decade-plus later, well, things have changed.

I believe Zinzi Clemmons’s assertion that Díaz forcibly kissed her when she was a graduate student. In 2018, as #MeToo was empowering people to speak up about sexual harassment and assault, Clemmons publicly accused Díaz of mistreating her, elevating whispered rumors about “bad-boy behavior” to something more concrete. Clemmons, a debut novelist, first stood up at an event in Australia, then detailed on Twitter that she had invited Díaz to speak on diversity at a Columbia workshop. “I was an unknown wide-eyed 26-year-old, and he used it as an opportunity to corner and forcibly kiss me. I’m far from the only one he’s done this to, I refuse to be silent anymore.”

Her public accusation was a reaction, in part, to an essay Díaz had published in the New Yorker revealing he’d been sexually abused as a child. The painful revelation was applauded by some, but seen by others as a cynical move to guard against possible MeToo accusations, such as Clemmons’s, which followed. At first, it looked as if Díaz’s positions at MIT, the Boston Review, and on the 19-member Pulitzer Board of Directors were in jeopardy, but he remained on all of them.

That’s a lot. So, I turned to The Road first. Here’s the setup: A man and his son trudge across a frozen, gray post-apocalyptic America, barely surviving on the scraps left behind by a ruined civilization. In the novel, McCarthy turns the narrative gifts he’d previously used to render the long-ago Southwest—gorgeous and spare, antique, pocked with horrible violence—to a ghastly future:

In the evening the murky shape of another coastal city, the cluster of tall buildings vaguely askew. He thought the iron armatures had softened in the heat and then reset again to leave the buildings standing out of true. The melted window glass hung frozen down the walls like icing on a cake. They went on. In the nights sometimes now he’d wake in the black and freezing waste.

The world has been turned to ash, no animals or growing things left. Yet the determination and bond between the father and son is so entrancing that Oprah picked it for her book club, getting the publicity-averse McCarthy to join her on TV. Primarily, as he would tell her, the book is about fatherhood and the love he felt as an older dad for his young son.

The fictional father does everything for his preadolescent boy: He scavenges for supplies, teaches him how to tell what’s safe to eat and drink, and protects him from the dangers they encounter. The dangers are, as the cliché goes, the most dangerous animal: man! (Spoiler alert!) The most fearsome men they encounter are cannibals. Some trap travelers then harvest flesh from the still-living captives. A pair keeps a woman with them pregnant so they can feast on her offspring: Our protagonists find a baby on a spit. It’s genuine next level horror. However, this detail caught me up on this, my second read of the book. Wherefore this fecundity? Although they do hear a dog bark, there are no other animals—no cows or cats or rabbits or rats. There are no cockroaches or crickets. No crops or moss or new trees or weeds can grow. Why can humans reproduce if every other living thing cannot?

The babies-for-eating is 100 percent ghastly, but it also showcases how good the father is. He isn’t eating his son; he’s protecting his son. By contrast, the boy’s mother abandoned them. About 60 pages in, having survived the apocalyptic calamity, the wife callously, bitterly walks away from her pleading husband and sleeping child to commit suicide.

Jeez, I thought, reading it this time around, it must have sucked to be McCarthy’s wife and see that portrayal. A whole book of love for a son while the mother, in the scant few pages where she appears, is cruel and ungrateful. It seemed like a rebuke. In his press appearances, McCarthy spoke piously of parenting, and no one seemed to notice that the mother was left out. It wasn’t until 2020 that I put together the fact that the same year the book was released, McCarthy and the mother of his beloved son divorced.

Aaaaand… now we arrive at The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. Carmen Maria Machado, whose short-story collection Her Body and Other Parties was a finalist for the National Book Award, has characterized Díaz’s work as “overtly misogynist.” Others, including Díaz, counter that the books portray characters whose ideas and beliefs are up for critique. The key character here is Yunior, who is often featured in Díaz’s short fiction and is the narrator of Oscar Wao. He tells the story of Oscar, an overweight Dominican kid in Patterson, NJ, from his childhood until his predicted death in his twenties, but that’s just the scaffold on which the book hangs.

Yunior also tells the story of Oscar’s sci-fi and fantasy geek passions; his eternal lovelornness; his sexy ambitious sister; their sexy ambitious mother; Rafael Trujillo and his cruel reign in the Dominican Republic; a foster parent; murderous thugs, sexual predation, curses, unfulfilled crushes, a grandfather’s mistake, and much much more. The narration is breathless, funny, roller-coaster, virtuosic. The book won the Pulitzer Prize and a stack of other awards, hit bestseller lists, and became a staple on college syllabi. The voice overwhelms with its capacious sentences, overflows into footnotes (in keeping with David Foster Wallace, a way to signify Serious Literariness). Although I’d read Díaz’s debut collection Drown and been keeping up with his short stories, this is the first time I’d had a chance to read The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. It’s impressive. In addition to its verbal flair, the book is doing a lot of work: It puts Spanish next to English, mixes Tolkien and music and sports and classical references and the Marvel Universe and Japanese fan culture and D&D, all without slowing down to explain.

Beli had the inchoate longings of nearly every adolescent escapist, of an entire generation, but I ask you: So fucking what? No amount of wishful thinking was changing the cold hard fact that she was a teenage girl living in the Dominican Republic of Rafael Leonidas Trujillo Molina, the Dictatingest Dictator who ever Dictated.

And from a footnote:

What is it with Dictators and Writers, anyway? Since before the infamous Caesar-Ovid war they’d had beef. Like the Fantastic Four and Galactus, like the X-Men and the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, like the Teen Titans and Deathstroke, Foreman and Ali, Morrison and Crouch, Sammy and Sergio, they seemed destined to be eternally linked in the Halls of Battle.”

If these intersections between pop culture and literature are common now, they were less so then. And they’re executed pretty much flawlessly. But instead of the above I could have easily pulled a quote that showcases the way women are objectified, or misogynistic ideas shared without apparent critique. In Oscar’s perennial inability to get a date, the plot’s engine, I learned far too much about the way Dominican-American male culture (or supposed culture) demands its men be great at both seducing women and cheating on them. If you want to look at the text for evidence of misogyny, it’s not hard to find. And yet. It’s undeniable that Díaz opened up a space for integrating Spanish and English in literature and on bestseller lists, foregrounding contemporary Latino/a/x-American culture for a general audience, in a way that other authors hadn’t been able to do.

The Road has its long tail, imagining survivors wandering a depopulated landscape like The Walking Dead. But in 2020, the book’s gray landscape seems like a failure of the imagination. We have faced plagues and pandemics and fires and floods, and the natural world continues to react and change and die and grow anew. If humans can survive, then surely there would be plants and animals and insects also adapting to this new terrible world. The real horror story—of climate change, disease, disaster—is one we have to face collectively. There is something deeply selfish and self-important in the father-and-son love story that excludes all else.

As for The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, it can be seen as a work of genius or a work of misogyny—I think it’s both. But publishing continues to have a whiteness problem, and Díaz has played an important role in making room for other Latino/a/x writers to have a chance at success. I expect that his offenses will get his book eliminated from this contest, but nevertheless, the novel has withstood the test of time better than its opponent.

Match Commentary

By Kevin Guilfoile & John Warner

Kevin Guilfoile: Judge Kellogg is spinning her gavel, Bruce Lee nunchucks-style, across a minefield, John.

Perhaps more than anything the Super Rooster is an exercise in context. We took the 16 novels that were most beloved by our judges over the years and now we’re asking which of them is most beloved among this particular gallery of reviewers. But Roosters are always about process more than results, and the process in every one of these contests is one in which the books are reevaluated in the present. How do they stand up against all the novels we’ve read since? Do they still seem as wise and inspired in the age of MeToo and Trump and COVID-19? Does our perception of them change given what we have learned about their authors?

Both of these books look quite different than they once did, I suppose.

John Warner: There’s even another dimension to the context when we’re talking about how we may think about these books now: the change in ourselves and our own perspectives. I mean, when I was maybe 14 years old, I would’ve told you my favorite book (or one of them) was Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land. It’s a novel about an Earthling raised on Mars who comes back to Earth as an ultrawealthy celebrity who starts his own religion that embraces group sex. What’s not to like!

Now, as a grownup with a much more mature outlook on the world, Stranger in a Strange Land skeeves me out, as do my memories of 14-year-old John, who was not a bad kid in the slightest, but was, you know, a 14-year-old.

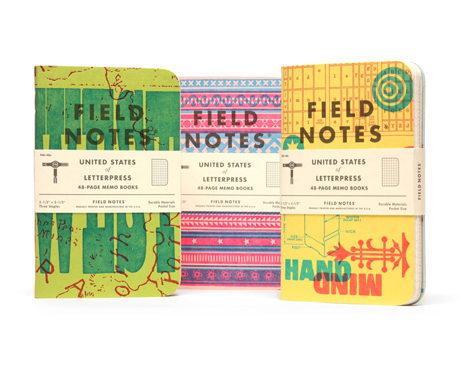

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.I was fully grown when I read both of today’s books, but the kinds of things I pay attention to has changed since I first read them. Particularly with Oscar Wao, I’m sure there are aspects that passed by without notice that would now cause far more turbulence.

Kevin: Judge Kellogg does a lot of difficult lifting here, identifying problems with each book, examining her own conflicted feelings, assessing the ways her attitudes toward each work have evolved.

I also like the way she not only reevaluates each work in the present, but reminds readers of their reputations in the context of their own time. What is most interesting about all the books in this competition, perhaps, is not how a novel was assessed when it was written, or how it has been reassessed in the present, but rather the curve between those two points, the journey every novel takes from its publication date to its place on today’s backlist. Some books don’t survive the trip. (I felt a pang of recognition as Judge Kellogg recounted the ways The Road simply doesn’t hold up in the days of coronavirus. I was well into writing a pandemic novel when the real thing hit and my interest in writing quarantine fiction developed an inverse relationship to quarantine reality.)

John: Both books, to some degree, have been overwhelmed by subsequent events, and as a professional book recommender, neither is one I’ve felt compelled to recommend recently. As an apocalypse novel, The Road is a little one-note, even if that note is awfully compelling during the reading experience. I taught the novel back in 2008, in a contemporary literature class themed around the apocalypse, and it was by far the novel students had the most visceral reaction to. I remember one student being a little upset that I’d made them read it because the roasting baby scene was so upsetting.

But it’s another book that was part of the course that I think resonates more strongly with today: Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake, which also involves a pandemic, in which people are required to give themselves over to the protection of corporations, like pharmaceutical companies, to merely survive. I know The Handmaid’s Tale is getting a lot of play lately, but don’t sleep on this one if you’re gaming out the future awfulness.

I did not reread these books for the Tournament, though I did go back and pull out my copies and reflect, and Judge Kellogg’s ruling that Oscar Wao holds up as the superior work despite it being colored by the additional context of time and information, feels quite sound to me.

Kevin: Every match in this Tournament is a battle of heavyweights, but some are more Ali-Frazier-like than others. Tomorrow, Toni Morrison’s A Mercy meets Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall with Will Chancellor ringing the final bell. Bring the smelling salts.

New Super Rooster merch is now available at the TMN Store. As a reminder, Sustaining Members receive 50 percent off everything in our store. To find out why we’re asking for your support and how you can become a Sustaining Member, please visit our Membership page. Thank you.

Welcome to the Commentariat

Population: You

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

- Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

- If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

- While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus

tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “ Dumbledore dies .” - We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.