-

Oct. 14, 2020

Opening Round

-

Adam Johnson

The Orphan Master’s Son

v.

The Good Lord BirdJames McBride

-

Judged by

Chelsea Leu

Somewhere in the weeks that I was reading and thinking about these books, news broke that one of the most alarming premonitions of the disease keeping us all inside is a loss of smell and taste. Every time I scrubbed my hands with lavender-scented foaming hand soap, I huffed it greedily; every time I crammed a fistful of Gardetto’s snack mix into my mouth, I savored its blood pressure-elevating levels of salt. I’d been confined to my apartment for a couple weeks—long enough for the effects of isolation to take hold, not long enough to become inured to them (if that’s possible)—and I feared that a certain cottony deprivation was descending on all my faculties. How could I make decisions, even decisions as seemingly easy as whether I liked a book or not, when I had no idea what was going on?

The protagonist of Adam Johnson’s The Orphan Master’s Son knows a thing or two about operating under sensory lack. Nine pages in, Pak Jun Do becomes a tunnel soldier for North Korea, a country that’s been practicing social isolation for decades. But he doesn’t stay a soldier for long. Jun Do’s life jumps from absurd circumstance to absurd circumstance: He helps kidnap people from Japan for the government, monitors transmissions on a North Korean fishing vessel, gets interrogated and tortured, is labeled a national hero, flies to Texas to meet a senator, and ends up in a brutal prison camp, in one long, bewildering chain of events whose disjointedness seems to be the point. And that’s just the first half of the book. The second half finds Jun Do utterly transformed—he’s somehow usurped the identity of high-ranking Commander Ga, and has been hauled into North Korea’s interrogation center for murdering “his” wife and children. We figure out how he gets there through a series of interleaved narrative threads that features a rivalry between two teams of interrogators, a climactic hostage exchange, and a romance narrated with impossible precision over governmental loudspeakers like a doomed, soap operatic radio play. The book, in short, is absolutely bonkers.

“You know what you are?” someone says to Jun Do. “You’re a survivor who has nothing to live for.” And so he was, I realized. Jun Do is a carefully constructed absence—we have no idea what he wants out of life, and neither does he. Which, to my striving, capitalistic American mind, comes off as uncanny. But in North Korea, Johnson points out, wanting things from life other than to survive is a luxury. “His whole life, he’d been assigned to work details without warning or explanation. There’d never been any point in asking questions or speculating on why—it never changed the work that had to be done.”

Jun Do’s story, in other words, has been taken from him, in a land where the stories of the state are all-important and the stories of individuals not at all. Or, as Johnson puts it after someone on the fishing vessel tells Jun Do about a former crewmate, “Real stories like this, human ones, could get you sent to prison, and it didn’t matter what they were about. It didn’t matter if the story was about an old woman or a squid attack—if it diverted emotion from the Dear Leader, it was dangerous.” The stories of individuals take on even more of a radical cast in the book’s second half, where Jun Do/Commander Ga must convince Commander Ga’s wife, famous actress Sun Moon, that he is a good man who loves her unconditionally, despite the fact that he’s never met her before. The real problem, we realize, is one of intimacy: Real relationships are impossible without truth, which the regime utterly destroys.

This is a book that manages to be funny even as corpses litter prison camps, tattoos get carved out of bodies with box cutters, and people eat moths and freshly harvested ox jizz to survive. Technically, The Orphan Master’s Son is a masterpiece. But the book does lay it on a bit thick. Jun Do had just arrived in Texas when I sat up from my bed (where I had been flopped in a trance, reading) in realization. Jun Do—like John Doe! But then, 10 pages later: “John Doe? Isn’t that the name you give a missing person?” says the senator’s maid. “’Actually,’ [the senator’s wife] said, ‘I don’t think a John Doe is a missing person. I think it’s when you have the person, just not his identity.’” Then: “’A John Doe has an exact identity,’ [the senator’s aide] said, and considered the patient. ‘It’s just yet to be discovered.’” Well, thanks for specifying. Then, too, some sentences sprinkled throughout were so self-consciously meta I had to roll my eyes. Less than halfway through the book: “He had a horrible feeling that this story was nowhere near finished.” (Me too, I wrote in my notes.) “The more detailed he made his story, the more strange and unbelievable it seemed to him.” “If only there were a place here for a person who gathered human stories and wrote them down.” All these touches give the novel a strangely propagandistic flavor—and not just because it nails the overblown mythologizing of North Korea’s official pronouncements.

The Good Lord Bird might be set in a completely different place and time—America, 1850s—but its protagonist, like Pak Jun Do, must lie about himself in a violent society to survive. Henry Shackleford is a young slave who is freed somewhat against his will when white abolitionist John Brown storms a Kansas Territory tavern and whisks Henry away. (Henry’s father is killed in the process.) Brown mistakes Henry for a girl and nicknames “her” Little Onion, and Henry/Henrietta tags along as Brown and his ragged band engage in skirmishes with Pro Slavers and kill slavery sympathizers with swords—and eventually, a few years later, execute their famous raid on Harpers Ferry.

It doesn’t quite sound like a romp, but it is, mostly due to Henry’s wry, pungent narration—he never says or does quite what you want him to. He spends his first stint in freedom scheming ways to return to bondage, and casts a sympathetic eye toward his enslavers. “Miss Abby was a slaveholder true enough, but she was a good slaveholder. … She runned a lot of businesses, which meant the businesses mostly runned her.” When he becomes the cleaning girl at a brothel run by the aforementioned Miss Abby, he scorns the darker, more unfortunate slaves who live in the pen outside, and when a few of them are put to death for organizing an uprising, his response is something of a shrug. “I ought to say here while I weren’t for the hanging, I weren’t totally against it neither,” he says. “Truth is, I didn’t care too much either way.” He’s as reluctant an adventurer as Bilbo Baggins—all he wants is to be well-fed and comfortable, and to not get killed. Principles, for him, are a bit beside the point.

Henry/Henrietta/Onion is, in fact, the perfect foil for John Brown, who comes off like a charismatic but irregular frontman (or maybe a cult leader) and is easily the best part of the book. Brown prays for hours, marathon sessions that the rest of his band grit their teeth and endure as their food gets cold. While Henry is preoccupied with his own physical comfort, Brown happily lives for months in the wilderness subsisting on turtle soup or roasted bear, and believes that everyone has the same ironclad ideals he does and is willing to go just as far for them. Ironically, he constantly points to Onion as a shining example of noble self-sacrifice. I like the way Henry diagnoses him at the very beginning of the novel, when Brown first mistakes him for a girl: “Whatever he believed, he believed. It didn’t matter to him whether it was really true or not. He just changed the truth till it fit him. He was a real white man.”

The heart of the novel rests precisely on that relationship between the truth and the color of your skin. “Truth is, lying come natural to all Negroes during slave time, for no man or woman in bondage ever prospered stating their true thoughts to the boss,” Henry notes early on. “Much of colored life was an act.” Just like, we understand, pretending to be a girl for the majority of the novel. But lying, while necessary, is also untenable, destructive to the human soul, as Henry realizes at the end when he’s in the thick of preparations for the Harpers Ferry siege and heartsick with love for a white woman. “If you can’t be your own self, how can you love somebody? How can you be free?” But I spent most of the book wondering why exactly Henry spends so long living as a girl, and 346 pages felt like a long time to wait for an answer.

It struck me, as I closed The Good Lord Bird at around three in the morning, that both of the books I had just read made me feel the same exact thing: nothing. Which I found troubling, and not just because it was approximately three hours after the deadline to tender my decision. Both books were undeniable accomplishments, obviously sweated over, the products of years of research. And they had both triumphed in previous Tournaments, which meant they had both already survived a gauntlet of discerning Tournament judges. So why did I feel oddly cold toward these books? I could appreciate them intellectually, but I didn’t love them. Why, when I tried to parse through my thoughts, did I gravitate toward listing their flaws rather than appreciating their merits? What did it say about me, I wondered with a tinge of alarm, that these books make so little impact? Had I lost, in my confinement, my own taste?

I think now that I was deeply skeptical about both of the protagonists, who seemed more like emissaries of an idea rather than truly imagined people. (I’ve deleted an entire side rant about how unconvincing the characters’ romances are.) Both novels are sort of picaresque, which require that a reader be entertained by or at least interested in what happens to their protagonist as he gets in and out of various scrapes. But I simply couldn’t bring myself to care about Jun Do or Henry, and so the plottier elements of the books—and these books have a lot of plot—were a slog, even more so because I knew this was all building up to some sort of lesson. I didn’t want big ideas, profound abstractions. I wanted people. People with glorious particularities, people I could see clearly (as opposed to, say, pixelated through their webcams or more than six feet away), people who were so sharply rendered that they could convince you they really existed, and could thus make you feel less alone.

I took a shower. I slept on it. The next morning, I stared at the books’ covers, both adorned by shiny gold stickers that seemed to rebuke me (The Orphan Master’s Son’s Pulitzer, The Good Lord Bird’s National Book Award). And then I chose The Orphan Master’s Son, mostly on the strength of a character known simply as “Interrogator Number 6,” who slowly begins to realize his total isolation, even from the elderly parents he cares for. “Father, is it just about survival? Is that all there is?” he asks. His father, who’s afraid of him, doesn’t answer. Reading this, hoping that my own parents were safe in their home 400 miles away, how could I not feel something?

Match Commentary

By Deena Frankel & Andrew Womack

Andrew Womack: Deena, welcome to the commentary booth! Could you introduce yourself to the readers?

Deena Frankel: I’ve been following the Rooster since 2010 or 2011. I started as a humorous protest against that other March Madness that overtook my colleagues every spring, and every year since I’ve read everything on the shortlist at least.

I live in Vermont where I am an oral storyteller (ala The Moth), performing around New England. When I’m not out blathering, I am a freelance writer and designer, and a fiber artist. I was a Jill of Many Trades in my conventional working life, from film festival director to government official to electricity policy maven.

Andrew: And how would you describe yourself as a reader?

Deena: My reading taste is pretty catholic, excluding only romance. I used to say I didn’t read science fiction, but in the past couple of years it seems reality has been so fiction-like that I’d be missing some of the best contemporary writing if I eschewed speculative worlds. As a reader, I’m sort of a dinosaur who has crossed the K-T boundary: I love big old plotty novels, but I am also hooked on contemporary writers who are experimenting with the novel form. And I love good sentences.

Andrew: What was the last sentence you underlined?

Deena: I am part of a literature group that meets every Tuesday. We are reading a series of plague novels, including Blindness, The Plague, and Decameron. I’m amazed at how much humans actually have learned and forgotten about pandemics. Camus:

In the memories of those who lived through them, the grim days of plague do not stand out like vivid flames, ravenous and inextinguishable, beaconing a troubled sky, but rather like the slow, deliberate progress of some monstrous thing crushing out all upon its path.

I know that’s bleak, but you are just lucky I didn’t quote Saramago, so much darker and less hopeful in the end.

I’d like to know what you underlined last?

Andrew: Here it is: “I could sense that nostalgia was overriding reason and that there would be no compromise,” from How Music Works by David Byrne. This is a book I reread quite a lot, and I love that line. That part is actually about the closing of CBGB, but it can apply to so much else.

Deena: That’s on my TBR shelf; I’ll have to move it up in the pile. Great quote.

Andrew: In her judgment, Judge Leu says, “Both of the books I had just read made me feel the same exact thing: nothing.” I know the feeling! How about you, can you relate?

Deena: I appreciated her implication that the pandemic was taking its toll on what she needed from books. But frankly I was shocked that a person could feel nothing from these two particular novels. Maybe if I hadn’t read them pre-Covid, I’d feel as she does. What do you mean when you say “I know the feeling!” Do you mean that in general or in particular to today’s contestants?

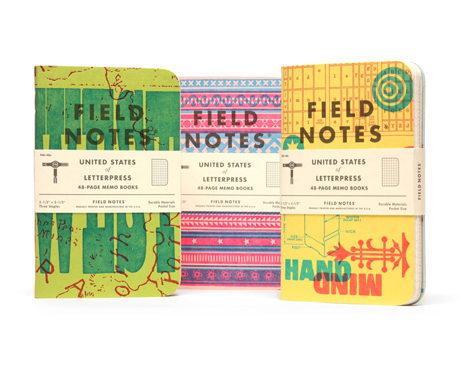

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.Andrew: For me it’s more of a general thing with certain books. I have a hard time abandoning a book. I will finish it, whether or not it’s working for me, and no matter the length. Conversely, I’ll stop watching any streaming movie or series 20 minutes in, never to return. What about you? Are you a diehard finisher or are you more likely to cut bait?

Deena: My spouse is a finisher, and I admire his ability to keep going no matter what. He has become a serious fiction reader in recent years and I have yet to find a book that tests his endurance. I keep moving Infinite Jest up to the top of the pile.

Andrew: Look out, TBR pile structural integrity!

Deena: I don’t mind working hard as a reader: James Joyce, Henry Miller, George Perec. I find myself most likely to give up when I find the characters’ lives trivial. I have little patience these days for the struggles of upper middle class urbanites. The last book I gave up on was actually a ToB summer read, All This Could Be Yours.

As for electronic media, I don’t think I can compare one to the other. Generally I know something about a book before I pick it up. I’ve probably read some reviews, and maybe a few sample pages, so I’m a lot less likely to start on something I won’t want to finish. But with streaming film and television, I find myself falling for the trailers and the hype and giving up in the first 20 minutes more than half the time. It just doesn’t feel like the same kind of commitment as opening a book.

Andrew: Books 1, Everything Else 0.

Deena: I do agree with Judge Leu, however, that the dumpster fire that is 2020 had a big impact on what I read and watch, especially at the beginning of the pandemic. I wondered when I read her decision in this round whether her choice of lens would have been different if the times hadn’t been so completely bizarro.

Present context aside, Judge Leu seems to be craving empathy or identification from these characters. I guess this gets at the most personal aspect of reading: What do you want from a book. As a reader my first question is: What was the author’s project? Then I’ll go where the book wants to go if it goes there convincingly. I can’t think of two books that more fully realize the places their authors sought to go. I agree with Judge Leu that they are both essentially picaresque, and they are certainly satirical. (An interesting decision by the ToB to pit two similarly matched beasts head to head.) I was happy to be swept along on the rides that each of them offered on its own terms.

Andrew: In fact, why these two books are facing each other in the opening round—and really, why all the books are arranged as they are in the brackets—is for purely chronological reasons. Any similarities may have everything to do with our tastes at the time, or perhaps even trends in publishing. (For what it’s worth, we toyed with other ways of laying out the matches, but liked how it felt more like different eras and times this way. A greatest hits, if you will.)

Deena: Interesting that these two books, with so much in common in a way, were consecutive winners: both meticulously researched historical fiction, big books, award winners. If I were in charge, I think I would still have put these books together regardless. My method would have been to match books up by weight. These two books would still have met in the opening round at 417 pages and 443 pages. And this method would have produced some dream matchups, such as Cloud Atlas (509 pages) versus Wolf Hall (604 pages), and Fever Dream (183 pages) versus A Mercy (167 pages), and The Road (241 pages) versus Normal People (273 pages).

Andrew: <frantically taking notes>

Deena: But kidding aside, your method does hold a mirror up to social trends, doesn’t it! I notice for example, that outright satire doesn’t win until the second half of the 16 years, and that the racial and ethnic diversity of the winners has increased greatly in the past decade.

Andrew: Looking back at the early years of the ToB, it feels like such a completely different event. What seemed valid or important to us in 2005 simply isn’t now, and vice versa. Which makes me think about the David Byrne line again.

Coming into this match, had you read either of these books? Were you rooting for one or the other?

Deena: I had read both books, but they are so different and each so successful at what each is trying to do that I couldn’t pick one. I had just finished reading Deacon King Kong, James McBride’s newest novel, and the music of his writing was ticking in my brain leading up to this round. But at the same time three very brutal books from the early 2010s—The Orphan Master’s Son, A History of Seven Killings, and The Narrow Road to the Deep North—have stuck with me and made me think about the ways that fiction can be truer than history. (Of course the same can be said of The Good Lord Bird but with a lighter touch.) So, truly I didn’t have a favorite and was very much looking forward to how the judge would sort this match out.

I was hoping for someone wiser than I to talk about some of the things that troubled or delighted me in each book. McBride’s use of dialect and stereotype, the landmines an author faces when making satire out of slavery. The jarring structural shift in Johnson’s book. The way both books comment on propaganda and what constitutes truth.

Andrew: Well, I can’t promise anyone—least of all me!—is wiser than you, but I know we have a bunch of people waiting to discuss these books in the comments. So let’s hand it over to them to tell us what they think about those specific topics.

Thank you, Deena, for joining us today! And now it’s over to the Commentariat to weigh in on these questions—and much more, I’m sure!

New Super Rooster merch is now available at the TMN Store. As a reminder, Sustaining Members receive 50 percent off everything in our store. To find out why we’re asking for your support and how you can become a Sustaining Member, please visit our Membership page. Thank you.

Welcome to the Commentariat

Population: You

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

- Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

- If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

- While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus

tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “ Dumbledore dies .” - We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.