-

Oct. 27, 2020

Semifinals

-

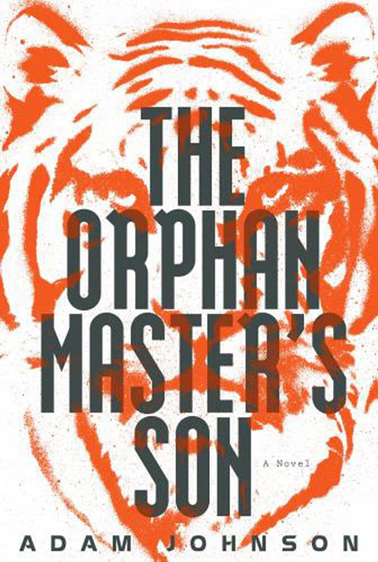

Adam Johnson

The Orphan Master’s Son

v.

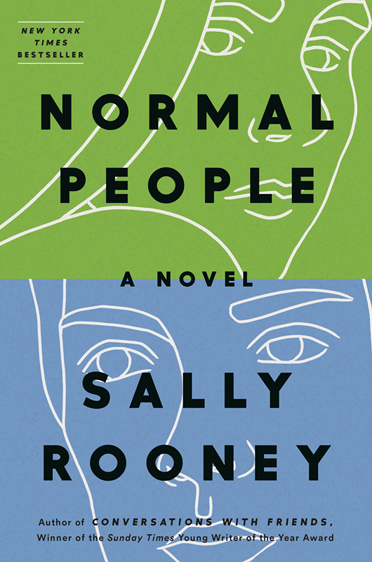

Normal PeopleSally Rooney

-

Judged by

Nicole Chung

I was in month two of pandemic isolation and dealing with a deep personal loss when these books showed up at my house, and I don’t mind telling you that I was neither what you’d call functional nor raring to make progress on the ol’ TBR. The books just sat there for weeks until my husband decided to read them. He sent me a 2,300-word, very mixed review of The Orphan Master’s Son. About Normal People, he said, “It’s a quick read. She doesn’t put her dialogue in quotes? But I know that doesn’t bother you.” So, you can’t say he pre-biased me, either way.

I know some Koreans who consider The Orphan Master’s Son to be appropriative—maybe not like American Dirt, but solidly in the genre of White Authors Writing About a Culture That Is Not Their Own in a Way That Doesn’t Always Feel Great. There are Koreans who don’t feel this way, of course, and then there are Koreans like me: I’d never read or formed a solid opinion about it. I was pretty happy not having an opinion about it, to be honest; that I must now supply one, in a public forum no less, strikes me as just slightly unfair. On the other hand, I was glad to be assigned Normal People, because it had been on my list for a while and I assumed zero fellow Koreans would get mad at me if I wound up liking it. Also, I’ve been thinking about watching the miniseries. Have we thought about a Tournament of TV Shows Based on Books? Like have we given that the consideration it deserves?

I love the Tournament of Books, and hope I am not fired yet.

As soon as I could focus again, I wound up flying through Normal People. Sally Rooney is just really fucking readable, as you all are probably aware, even if this book is not your favorite (it wasn’t quite mine). At times I really struggled with Connell and especially Marianne—among other things, I wanted them to have some tough conversations and make some decisions together, but that’s likely my age and general crankiness showing. By the final third or so, I found that I’d become invested in their story—you know how characters’ choices start bothering you, and you realize it’s because you care?

At the root of my annoyance was a wish for these two to be OK, whatever that means for them. Even if you find Marianne or Connell slightly insufferable, sometimes it’s insufferability with a ring of truth, a shiver of recognition, because you probably remember being a teen and then a brand-new adult: eager to find your place and your people, unsure how much to reveal or how to navigate the thrilling and terrifying demands of intimacy, hyper-aware that every quotidian moment or choice or exchange might balloon into one of overwhelming importance.

Even in memory she will find this moment unbearably intense, and she’s aware of this now, while it’s happening. She has never believed herself fit to be loved by any person. But now she has a new life, of which this is the first moment, and even after many years have passed she will still think: Yes, that was it, the beginning of my life.

I felt a bit let down by the last section, wondering how much Marianne had really changed or increased in agency, wishing for more clarity about where she and Connell were headed. But then again, they’re so young. Would an ending with a greater sense of finality make sense? Probably not—and it’s partly the wide-open possibility and potentiality of these characters, individually as well as together, that packs so much of the book’s emotional punch.

It’s fair to say that far more happens in The Orphan Master’s Son, a book both helped and hurt by the fact that I encountered it in 2020: The narrative is sometimes perplexing or impossible to trust, but who expects anything different anymore? Still, left to my own devices I probably wouldn’t have chosen it—it’s a brutal story about a brutal regime and like, I’m already pretty depressed. But Nicole, a bunch of you are thinking, what about the state propaganda drop-ins? What about the glittering satire: Didn’t those moments pack some levity? I see it, but for me to get the most out of those interstitials, I think I’d have needed a slightly better handle on the reality of life in North Korea—more knowledge of what was being satirized?—and that’s tough, for obvious reasons. Of course, this is precisely the draw of the book, for so many: its attempt to offer a peek into an isolated country most of us know little about. But is that what this book delivers? While Johnson did a lot of research, he didn’t get to speak with anyone beyond his state-approved tour, and so much, by necessity, is invented. And yes, I know it’s fiction, but every time someone (…always a white person…) has recommended this book to me, they’ve said how much they appreciated “the window into North Korea!”

I always wonder what I’m doing when I read lots of made-up horrors about a place with plenty of real-life horrors. Am I empathizing? Am I dehumanizing? Kinda tough to claim I achieved the former this time, partly because so much is left to the imagination when it comes to characters’ inner thoughts and lives and histories. In the first part of the book, especially, detailing Jun Do’s journey from one difficult posting to the next, we don’t learn a great deal about what he or other characters think or feel about their circumstances. Many will accept this as part and parcel of a story that leans so hard on themes of state control, propaganda versus reality, power and who wields it. But without agency (denied to them by the state) or real interiority (rarely glimpsed on the page), the characters didn’t feel real to me.

I still wanted to understand how everyman Jun Do pulled off the transformation to Commander Ga, learn about his relationship with Sun Moon and their escape plan (also, I’m also a sucker for a Casablanca reference). I appreciate that the book had me continually questioning what a story is, how changing it can also change how we perceive reality—the state controls the narrative in Johnson’s North Korea, a point driven home over and over:

Where we are from, he said, stories are factual. If a farmer is declared a music virtuoso by the state, everyone had better start calling him maestro. And secretly, he’d be wise to start practicing the piano. For us, the story is more important than the person.

It becomes clear that these characters have no idea what “freedom” is. They just want to escape the cold, unyielding terror of their lives, and this is often what defines them. Some will say this must be accurate, life under a dictatorship, but one result—for me, at least—was a story of Korean characters I could never quite see or grasp or believe in as fully human. If I were not a Korean American reader, this would no doubt be easier to overlook. As it is, to be fully swept up in The Orphan Master’s Son would have required a kind of compartmentalization I believe I’d find challenging in the best of times, which these, my friends, are not.

Before this Tournament matchup, I wouldn’t have said that I look for characterization first in fiction, but now I’m wondering if I do. Long after I’ve forgotten/stopped caring about the actual events in Normal People, I’ll remember the crystalline detail of zoomed-in character studies, the crafting of two intense protagonists I struggled with at times but wound up caring about anyway. Also, dialogue sans quotes doesn’t bother me in the slightest. I’m advancing Normal People.

Match Commentary

By Kevin Guilfoile & John Warner

Kevin Guilfoile: Judge Chung’s verdict gave me a lot to think about. I love The Orphan Master’s Son, and raved about it when it made its first appearance here in the ToB. I never thought about whether it was an accurate depiction of North Korea, though. The North Korea in the book seemed to me like a fantasy world, not an avatar for the actual place. And that in turn seemed like a metaphor for the alternative reality that decades of Kim dictatorships seemed to have created for its citizens. But it also didn’t occur to me that, to a Korean American reader, that kind of appropriation might feel problematic. I still defend my reading of it, but perhaps Judge Chung has exposed an empathy blind spot in me.

John Warner: I was aware that Adam Johnson did a lot of research for The Orphan Master’s Son while writing the book, but I had a similar reaction to you, that it was impossible to know if the book was at all accurate because it’s a world so few have access to. I don’t think I ever thought I was getting a peek into North Korea, so much as the idea of North Korea was being used as a jumping-off point for a sprawling imaginative work. But unlike a fully invented place, North Korea is real, so we run into the issues Judge Chung identifies.

Over the years, you and I have talked about the “gravitas gap” between books often playing a dispositive role in the decision. I feel like there’s a significant gravitas gap here, but Normal People cleared it, and marches on.

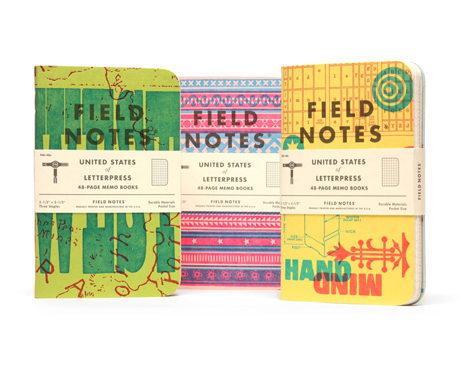

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.Kevin: Relative to The Orphan Master’s Son, there isn’t much incident in Normal People, as Judge Chung points out. I mean obviously things happen (the BBC and Hulu turned it into a 12-hour miniseries which is about six more hours than it took me to read), but compared to The Orphan Master’s Son, the stakes feel kind of low. They are intensely personal stakes, however, and when you draw two characters as acutely as Rooney does, even small matters seem heightened. As Judge Chung says, “…you probably remember being a teen and then a brand-new adult: eager to find your place and your people, unsure how much to reveal or how to navigate the thrilling and terrifying demands of intimacy, hyper-aware that every quotidian moment or choice or exchange might balloon into one of overwhelming importance.”

Ultimately when you have an author as skilled as Rooney is, it’s just a marvel to watch her work. If she played accordion as well as she writes, I’d probably be quite happy watching her for 12 hours on Hulu pumping the old stomach Steinway.

John: Judge Chung’s proposal of a Rooster of literary TV/Movie adaptations is intriguing and maybe we should do that, but I have a question more closely tied to our Super Rooster, namely, which entrants in our tourney have been most successfully adapted into the visual medium? Which book that hasn’t yet been adapted should be?

Kevin: By my count we have Cloud Atlas, The Road, Wolf Hall, The Sisters Brothers, and Normal People. The Good Lord Bird is running on Showtime right now, and The Underground Railroad is headed for Amazon Prime. I wonder which of these the folks in the Commentariat like the best.

John: If I know the Commentariat, they’ll be sure to tell us, but I’m going to put in my vote right now: not Cloud Atlas.

Kevin: Sigh. Yeah. I think filmmakers are going to have to take a couple swings at Cloud Atlas before they get it right, if anyone ever does. I have no reason to think the Wachowskis weren’t coming at the material from a place of love and respect, but that movie is just tonally wrong from the get-go, and then everything that follows from that (casting!) is a horrible miscalculation.

But there are some pretty good adaptations in this group, I think (i haven’t seen them all). I’m interested to hear what everyone thinks.

So Normal People advances to the Zombie Round, where it will have a rematch against the novel it defeated in the 2020 finals, María Gainza’s Optic Nerve. I have to say, John, Optic Nerve was one of the more polarizing books to ever vie for the Rooster, but it almost ran the table in last year’s ToB. Normal People, one of the most popular and acclaimed novels of the last few years, actually lost in the opening round and came back as a Zombie to win the Rooster. Nevertheless, it would really be jaw-dropper if Optic Nerve could turn the tables here and advance from out of nowhere into the Hella-Rooster championship.

New Super Rooster merch is now available at the TMN Store. As a reminder, Sustaining Members receive 50 percent off everything in our store. To find out why we’re asking for your support and how you can become a Sustaining Member, please visit our Membership page. Thank you.

Welcome to the Commentariat

Population: You

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

- Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

- If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

- While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus

tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “ Dumbledore dies .” - We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.