-

Oct. 15, 2020

Opening Round

-

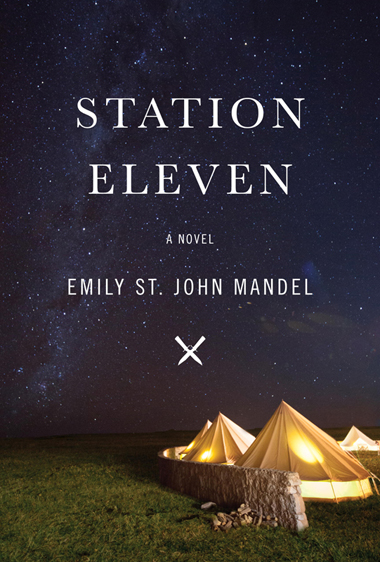

Emily St. John Mandel

Station Eleven

v.

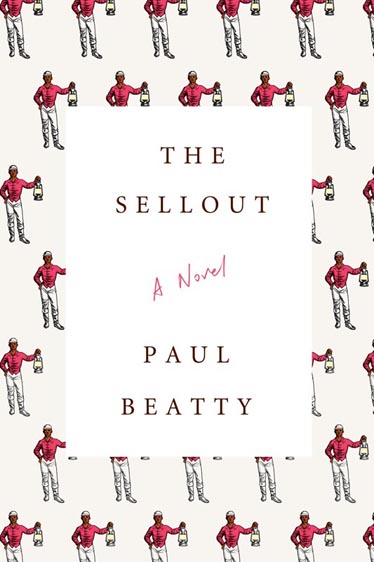

The SelloutPaul Beatty

-

Judged by

Rumaan Alam

No one could argue that Station Eleven isn’t prescient. Emily St. John Mandel’s novel depicts a humanity succumbing to a fast-moving and—spoilers don’t pertain to a book published six years ago—fatal flu. Here’s the beginning of the end for one of the many characters in the book:

Miranda woke at four in the morning with a fever. She fought it off with three aspirin, but her joints were knots of pain, her legs weak, her skin hurt where her clothes touched her. It was difficult to cross the room to the desk. She read the latest news on the laptop, her eyes aching from the light of the screen, and understood.

I missed this novel when it came out (who can keep up?) and found it strangely comforting to read as COVID-19 marched around the planet. While Mandel offers doom, she offsets the gloom: Station Eleven posits art as salvation, or the enduring characteristic of civilization, anyway. The novel’s plot sees a troupe of players wandering the Midwest, bringing music and Shakespeare to the citizens who have managed to survive. Yes, these people miss air conditioning and the million other comforts of modern life, but that art persists makes their survival worthwhile.

Writers have conjured dystopia as cautionary tale or overwrought metaphor. Mandel uses is it to give shape to the thrum of unease beneath modern life. The result is realist, not literally but aesthetically. That’s part of what makes the book so powerful: It’s almost a relief for readers teetering on the tipping point to read about a world profoundly changed. The more so since, in its strange way, Station Eleven gives humanity a happy ending.

It’s sad, but immensely enjoyable, because Station Eleven yields so easily to readers. Making a novel that is a beguiling little trap is obviously hard to do, otherwise every writer would do it all the time. If it’s a strategy that prizes storytelling over the individual sentence, so be it. Station Eleven is about theater but influenced by cinema, the narrative attention divided among a cast of players. I was irritated by the camera cutting away from the plotlines I liked best, and skeptical of what emerges as the novel’s plot, a maybe too-familiar story of a charismatic madman beguiling lost souls at the end of days. Some might find this tough to read during a global pandemic, but the best books are often discomfiting.

If Station Eleven makes readers anxious, Paul Beatty’s The Sellout has an utterly different effect: It’s one of a very small number of books to ever make me laugh out loud. It’s the kind of novel for which plot summary seems beside the point, but so you know: The narrator is the son of a radical black academic, and in a complex scheme that (almost) makes sense, he reintroduces slavery in his hometown, a trick that gets him hauled before the Supreme Court.

The Sellout is deeply funny on the level of the line—so much so that it’s almost impossible to choose a snippet to quote here—but its accomplishment is its utter commitment to absurdity. Beatty’s book is often called satire, though it’s worth noting the author himself rejects this designation. Maybe because that’s not what he’s up to, and there’s no word for what lies beyond satire, perhaps because Beatty is the only person ever to venture there. An example: The man our narrator enslaves is a former Little Rascal:

I didn’t realize it then, but Hominy, like any other child star still standing in the klieg light afterglow of a long-ago canceled career, was bat-shit crazy. We thought that he was being funny: dry humping the TV with every low-angle shot of Darla’s exposed lace panties. “In real life that bitch wasn’t as stingy with the pussy as she was in the movies.” Slamming his pelvis into the screen, shouting, “That’s for Alfalfa, Mickey, Porky, Chubby, Froggy, Butch, that stuck-up punk Wally, and the rest of the gang!” punctuating his blue-balls roll call with increasingly violent thrusts.

Beatty gives us a laugh, but there’s music in his writing, a beauty to offset the coarseness. The essential ingredient in humor is intelligence, and you cannot but notice that this is a book reckoning with so much—Blackness, capitalism, California, the Bush years, I will not disrespect Beatty by listing it all. Turning the whole enterprise into a joke liberates the author to say what he wants on every subject he wants. You never stop laughing, but the endeavor of the novel is nevertheless dead serious.

Sometimes my experience of a book is colored by the circumstances under which I read it; I’m deeply fond of the novel Buddenbrooks, for example, but I acknowledge this is informed by the fact that I read it on a deserted Hawaiian beach. It’s a credit to Station Eleven that I could read it during this moment of pandemic and enjoy that discomfiting sense of recognition. Indeed, the book made me feel better about reality than I had in some time. But this is a way of talking about me, and not the novel.

Some books subsume us, overwhelm with their brilliance; reality falls away, whether you’re on a Hawaiian beach or a dentist’s waiting room. The Sellout tells us about the world in which we live, but does so by drawing us into itself wholly. It is electric and funny and so beautifully written that I kept stopping because I wanted to read a sentence aloud to anyone within earshot. The very point of this Tournament is the comparison of apples to oranges; impossible. Station Eleven is a very good book. The Sellout is a work of genius.

Match Commentary

By Kevin Guilfoile & John Warner

Kevin Guilfoile: We paired the books for the Super Rooster chronologically, which isn’t random, of course, but it is blind to each novel’s content and theme. Nevertheless, we couldn’t have had an opening-round matchup with two novels that were more of the moment if we had orchestrated it.

I loved Station Eleven, but, unlike Judge Alam, I’m not sure I would enjoy rereading it in the current environment, masked outside of my home, afraid of indoor bars and restaurants, passing most days inside my house, toiling alongside my remotely tethered wife and kids. Even Emily St. John Mandel has had reservations about the prospect:

Counterpoint: maybe wait a few months? https://t.co/mZduMr022L

— Emily St. J. Mandel (@EmilyMandel) March 11, 2020

John Warner: When the pandemic first hit and there were a bunch of articles about what pandemic novels we should be reading, Station Eleven was at or near the top of every list, and all I could think was how little I wanted to read pandemic fiction.

Emily St. John Mandel is a spellbinding writer, one of those people who just makes sorcery on the page. Her most recent book, The Glass Hotel, does not have the same big, conceptual hook, but the moment-to-moment rendering of the experiences of her characters put me under her spell, a “beguiling little trap” indeed.

Given Judge Alam’s notion that we may be able to find comfort in an apocalyptic pandemic novel even during a pandemic forces me to rethink my initial aversion. And in truth, I’m apparently not that averse, because my favorite novel of 2020 thus far is Lydia Millet’s The Children’s Bible, which is set against climate collapse, which is to say, pretty much what we’re living through right now. The novel itself is so thoroughly alive and even quite funny that there’s maybe a “whistling past the graveyard” feel to it. Does the art (as Station Eleven suggests) provide protection against even the worst possible presents and futures? (Judge Alam’s own apocalypse novel, Leave the World Behind, is also on my nightstand, FYI.)

Station Eleven argues that something can endure. Something must endure, and I suppose while I’m reading a book about the end of the world where the world hasn’t quite ended, there is some measure of hope. I wonder if or when we’ll get to the point when that solace can’t be achieved.

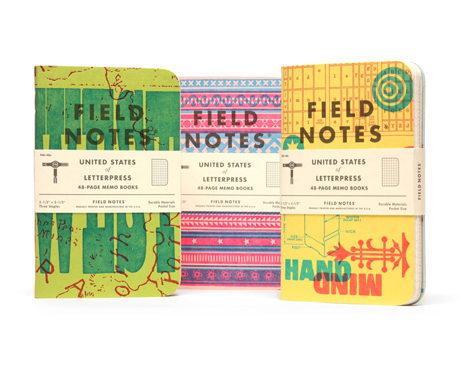

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.Kevin: The Sellout feels more necessary than ever. There is a disconnect for sure between its brutal humor and, say, the outrageous free pass given to Breonna Taylor’s murderers. (It feels almost inappropriate at this time to describe how fucking funny The Sellout is.) Yet they are different parts of the same story, and every American needs to hear and understand it.

John: I only planned on a refamiliarization with each of the competitors we’d be discussing, rather than a reread, but I picked up The Sellout and started reading and then kept going. Its resonances are even clearer now than a few short years ago. And yes, it is really fucking funny.

Kevin: Every year you and I get pushed further into the older cohort of any group that will still have us as members. We grew up in an age when we devoured a lot of The Little Rascals on TV, only because, in a 13-channel broadcast universe, there wasn’t much else on. It’s so weird now to think how much film shorts from the 1920s and ’30s dominated the children’s television landscape in the ’70s and early ’80s. It would be like if my kids had nothing to watch every day except The Funky Phantom or Green Acres, and also if The Funky Phantom were super racist. But it’s also weird that The Little Rascals lasted as a cultural institution for as long as it did without anyone going, “Ummmm, guys?” I stopped watching it when I was probably seven, but I must have sat through at least 100 hours of Our Gang and I don’t think I gave the stereotypes in that show a second thought until Eddie Murphy did his Buckwheat character on SNL.

I think a lot of old white guys like you and me go through much of our lives believing that because our intentions are good, we can’t be racist. But we are also oblivious to a lot of racism in which we are complicit, and it takes a Paul Beatty (or a Black Lives Matter) to punch us in the gut.

A lot of people don’t like being punched in the gut, of course, but fuck them.

John: As longtime members of our audience know, the “Biblioracle,” my weekly schtick at the Chicago Tribune, was born in this very space, and if one were to go back and catalog all of my recommendations I’ve made over the almost eight years at the Trib (well over 1,000 recommendations) they would see an evolution in my choices, a movement toward greater diversity in my picks. Part of this was intentional, a belief that championing perspectives beyond the default that looks a lot like old white guys. Those are my good intentions, but here’s something I’ve learned—it also makes for a much more enjoyable life of reading! The fundamental driver of my reading habit has always been curiosity. I like learning and experiencing things I don’t know, and exposing myself to a diversity of voices has been fucking great.

Kevin: When I was very young I read books that fit on a pretty narrow shelf, subject-wise. Mostly genre, mostly written by white men. To the extent there was a diversity of voices available to me on that shelf, I wasn’t aware of most of them. (I’m embarrassed to tell you how old I was when I discovered Octavia E. Butler.)

When I started reading more literary fiction, I had a couple authors I read religiously and they were also white men. I think I actually remember sitting on the couch in my parents’ living room and being very bored, and I picked my sister’s copy of The Accidental Tourist and thought, “This doesn’t look like anything I’d like,” but I started reading it anyway, and had this epiphany, “Oh wow! This is great!”

Still, we all fall easily into reading habits, and sometimes it’s a bit of work to stretch outside our comfort bubbles. Some years of the ToB (which definitely took place when we were all grown adults) have been rightly criticized for a lack of diversity.

That reading journey for me has been long, but it’s been satisfying.

Tomorrow, Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad takes on Samanta Schweblin’s Fever Dream. The former is one of the most (rightly) celebrated novels of the past 10 years. The latter is one of those books I was just talking about, one that I never would have picked up if not for the ToB and it was also one of the most viscerally exciting reading experiences I ever had. It seems like a mismatch on paper, but Fever Dream, probably the greatest longshot champion in Rooster history, has quite a few tricks in its pages.

New Super Rooster merch is now available at the TMN Store. As a reminder, Sustaining Members receive 50 percent off everything in our store. To find out why we’re asking for your support and how you can become a Sustaining Member, please visit our Membership page. Thank you.

Welcome to the Commentariat

Population: You

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

- Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

- If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

- While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus

tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “ Dumbledore dies .” - We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.