-

Oct. 12, 2020

Opening Round

-

Toni Morrison

A Mercy

v.

Wolf HallHilary Mantel

-

Judged by

Will Chancellor

Here I sit, foolishly, about to evaluate whether perhaps the most celebrated historical novel of my lifetime is “better than” a late-career triumph of a Nobel laureate. I’ll skip over the experience of reading about plague and smallpox outbreaks, respectively, amidst a global pandemic. And I’ll shelve, for now, my impassioned defense of objective aesthetics. Instead, let’s keep our caveats to the impossibilities of a) my offering so much as an emotional synopsis of a novel with motherhood and chattel slavery at its center; and b) judging one’s superiors, which I mention neither out of humility nor sycophancy, but because a trusted editor suggested I study up on Hilary Mantel to write the novel I’m currently working on and because Toni Morrison is one of a handful of authors whose work taught me how to read.

To that last point, I wish I could approach this as a paradigm-free, tabula rasa judge. But I can’t. I read for images rendered so closely that they overtake the visual part of the imagination and recruit feeling. Think Annie Dillard’s tree with the lights in it (Pilgrim at Tinker Creek), Alice Oswald’s little girl tugging at her mother’s dress and wanting only to be lifted on a hip (Memorial), or Virginia Woolf’s doomed moth struggling against the enormity of death (“The Death of the Moth”). Think of a strawberry containing summer storms in The Bluest Eye, or a sleep “more tranquil than the curve of eggs” in Sula, or a ghost child’s tiny handprints in a cake in Beloved. This is the world seen and related with full attention. We zoom in until we can’t get any closer and then, click, on comes the feeling vision, allowing us to fully inhabit what we’re reading. This is every shot in every Malick movie. This is what I think it means to wonder.

I say all this as a practical consideration: Dame Hilary Mantel is going to have to out-Morrison Morrison in order to advance. Wolf Hall is being judged by a reader whose atemporal, impressionistic way of engaging with fiction was formed by its opponent.

Coincidentally, I first read these books side by side about six years ago in an attempt to figure out how the greats write historical fiction in present tense. Reading for craftwork makes me feel like an entomologist looking through a loupe. One of these books was a beetle, offering up iridescent splendors with that level of scrutiny; the other more like a grasshopper, an anatomical marvel that made me reconsider how much spring can come from a pair of legs. I finished the beetle in two days. I only made it about 80 pages into the grasshopper. This time around was in many ways a different experience.

Wolf Hall begins with exactly the kind of closely felt image that brings a book to life. Thomas Cromwell’s father, Walter, has nearly kicked the life out of his son. Forehead flat against the cobbles, Thomas looks to the gate, thinking help might arrive. We move closer. The narrator describes a knotted strand of catgut that has sprung from the leather in Walter’s boot. The twine has cut Thomas’s eyebrow, blinding him. “So now get up,” Walter roars. Thomas thinks only of his dog as consciousness slides away like a river.

Rather than holding the reader at an introductory distance, Wolf Hall goes as close as possible—right at the outset. And in epic fashion (Muse, sing of “the rage of Achilles” or “the man of many turns” or “man’s first disobedience”…) Wolf Hall announces its theme in the first line: “So now get up.” This is the story of a bootstrapping self-made man. Mantel found a character manhandled by British (literary) history, dusted him off, and offered us a view of his fascinating interiority.

Wolf Hall is technically in the third person, but we live in the inner world of Thomas Cromwell—for these 600-some-odd pages we have his intuitive understanding of power, his immediate realization of motive, his mind spilling with grotesqueries and winding with the arcades of a memory palace. And yet, even though Wolf Hall shows us how a mind could memorize a Bible, it withholds the memories we want most to learn: What exactly did Cromwell get up to when he was abroad?

There’s a huge lacuna, in both the historical record and the text, about Cromwell’s doings in young adulthood. If I had to pinpoint one stroke of genius in Wolf Hall, it’s the decision to leave this period of Cromwell’s life an absent center of gravity. For resisting the urge to flashback, it wins a medal for heroic restraint in the service of story. It would’ve been so easy to give us young Cromwell up to no good in Italy, but instead Wolf Hall taps into the possibilities of silence. Cardinals and courtiers alike surmise that he has killed and made some sort of Faustian bargain, which deepens his mystique. As Cromwell ruminates, “A man’s power is in the half-light, in the half-seen movements of his hand… It is the absence of facts that frightens people: the gap you open, into which they pour their fears, fantasies, desires.”

Looking at Hans Holbein’s portrait of a piggy manchild fuming in timeout, you’d be surprised to learn that Tudor England’s most powerful men and women (Mary, Katherine, and Jane Rochford, in particular) desperately want to peer into that half-light. They see an odd charm in Cromwell and eagerly engage him in frank conversation. Cromwell never shines brighter than in these hallway confidences, which are again made possible by his inscrutability. Taken together, these asides reveal how Cromwell—magnetic menace; Iago but without the slight—wins promotion after promotion while expanding the realm of his sovereign. Wolf Hall, waxing Tolstoyan, tells us, “This is how the world changes: a counter pushed across a table, a pen stroke that alters the force of a phrase, a woman’s sigh as she passes and leaves on the air a trail of orange flower or rose water…” Mantel’s Cromwell shows that the details of human interaction, compressed in a novel, make up the strata of history.

Detail piles on detail and history happens fast. In a Guardian essay, Mantel writes how the present tense accelerates the novel, “The present tense seems natural for capturing the jitter and flux of events, the texture of them and their ungraspable speed.” For me, this ungraspability, which is in effect the external world of Cromwell, makes me want to return to the tenable interior world, to the close images that constitute identity.

It takes time to see things closely. Though we begin Wolf Hall with a deep view, the next 300-some-odd pages are… jittery. After introducing hundreds of characters and their machinations, a reader finally gets the chance to breathe deeply as the cook, Thurston, cranks out a perfect wafer. This moment in Part Four, Section Two, is when the narrative settles to my kind of pace. From Spring of 1532 until the final page, Wolf Hall draws focus in a way that summons feeling. And, wow, is that evident on the day Cromwell’s worldview forever changed as he was made to witness the Loller’s burning. He’s brought to the very front of the crowd, as “it will do him good to see up close.” And, indeed, the imagery is as close as it gets.

Cromwell supposes he was about nine, “he cannot remember the year but he remembers the late April weather, fat raindrops dappling the pale new leaves,” when a woman, a grandmother, is led to the stake for believing a communion wafer is the body of God. “A man said, not much fat on her bones, it won’t take long unless the wind changes.” But it does take long, longer than any other moment in the novel, just as the day takes greater importance than any other for Cromwell. The description could’ve ended here: “People who are not smiths think all fires are the same. His father had taught him the colors of red: sunset red, cherry red, the bright yellow-red with no name unless its name is scarlet.” But we move past the fire, to the skull, to the bones, to the “thick sludgy ash,” to a friend of the Loller who dips her finger in a bowl of greasy ash, wipes it on the back of his hand and resurrects her friend’s name, Joan Boughton.

What I presume attracts so many readers to Mantel—her pace, that grasshopper spring, the sense that History is happening and it’s all happening now—is what initially put me off of Wolf Hall. I felt whiplash and thought it would never again return to the slower pace of the opening, which, as I realized when I read this astounding description of burning at the stake, was idiocy on my part. While Mantel does typically arrive late and leave early, she occasionally lingers, maybe even loiters, maybe is lost in the almost unbearable reality of a moment.

A Mercy begins with a paragraph that is, at this point in the book, incomprehensible. Take the central image of the first paragraph: “You can think what I tell you a confession, if you like, but one full of curiosities familiar only in dreams and during those moments when a dog’s profile plays in the steam of a kettle.” Wait, which moments? That image of a dog’s profile in steam is too far of a leap from our starting point. Though it’s inscrutable now, we’ll return to that image as our protagonist, a 16-year-old named Florens who was born enslaved, is further dehumanized by crazed Puritans. Then, we see the same image closer: “The air is tight. Water rises to a boil in the kettle hanging in the fireplace. I turn and see its steam forming shapes as it curls against the stone. One shape looks like the face of a dog.” A Mercy’s gambit is to sacrifice a linear conception of time and ask the reader to accept being given everything at once, to trust that things will eventually come into focus. It’s risky. But the decision grants a deep interiority right away. Truth is, interrupt anyone’s inner monologue and you’re gonna get something confusing and circular spoken within an indecipherable vocabulary of signs.

The second paragraph of A Mercy offers a concession and a restart, “The beginning begins with the shoes.” We see a young woman, Florens, wearing “the throwaway shoes from Senhora’s house, pointy-toe, one raised heel broke, the other worn and a buckle on top.” First off, it’s a hell of a coincidence that both Wolf Hall and A Mercy begin by drawing our attention to shoes. The coincidence deepens as we learn that Florens will trade those heels for her enslaver’s boots. “They stuff them with hay and oily corn husks and tell me to hide the letter inside my stocking—no matter the itch of the sealing wax.” Hard not to feel that itch, that raw discomfort, on your inner ankle. And, with apologies to high school English teachers adamant on explaining trees, birds, colors, etc. as “x is a symbol for y,” the shoes do not represent any idea, they are the idea. We’re asked to look down at Florens’s feet and see the reality before us. We see how a discarded pair of heels could mean everything to her. We’re literally beginning in Florens’s shoes, building consciousness from the ground up, from soles too soft for the world.

Structurally, A Mercy consists of six chapters of Florens’s lyrical first-person-present interspersed with six chapters of close third-person-past accounts of 1) landowner and “reluctant” enslaver Jacob Vaark; 2) his wife Rebekka; 3) a native woman named Lina; 4) a “slow-witted girl warped from living on a ghost ship” named Sorrow; 5) bumbling neighbors Willard and Scully; and 6) Florens’s mother (minha mãe).

The tetrad of Florens/Rebekka/Lina/Sorrow invites a reading of shared female experience and the universal constriction of choice for any woman at the time. “Her prospects were servant, prostitute, wife, and although horrible stories were told about each of those careers, the last one seemed the safest.” Equating these experiences, however, is a mistake. Rebekka appears traumatized by her passage across the Atlantic as a mail-order bride. “‘I shat among strangers for six weeks to get to this land.” A Mercy is able to convey the indignity of that experience from Rebekka’s perspective and the helplessness of walking off the plank into a contracted marriage in 1690. But Florens’s mother’s account of the Middle Passage, which concludes the book, clarifies what is a humiliation and what is a horror.

In the ship’s hold, Florens’s mother longs for death, pretends she’s dead so that she might be thrown overboard to the circling sharks. “Unreason rules here. Who lives who dies? Who could tell in that moaning and bellowing in the dark that awfulness? It is one matter to live in your own waste; it is another to live in another’s.” Despite opting for death, she survives. And even though we hear gratitude, the imagery is infernal:

Grateful for the familiar heat of the sun instead of the steam of packed flesh. Grateful too for the earth supporting my feet never mind the pen I shared with so many. The pen that was smaller than the cargo hold we sailed in. One by one we were made to jump high, to bend over, to open our mouths. The children were best at this. Like grass trampled by elephants, they sprang up to try life again.

Can you see that trampled grass? Feel the overwhelming green spring of children? Feel the tension of that spring with the crushing force of “steam of packed flesh?”

The need in A Mercy is simple: Florens must find the blacksmith (the “you” of the Florens chapters) who installed an ornate gate on the Vaark farm and has now returned north. Ostensibly, she needs to find him to cure Rebekka. Actually, she needs to find him because she has been run over by love. “I will see your mouth and trail my fingers down. You will rest your chin in my hair again while I breathe into your shoulder in and out, in and out. I am happy the world is breaking open for us, yet its newness trembles me.” That word, “trembling,” suffuses the description of the blacksmith. Another, “hunger,” trails the blacksmith in Florens’s mind:

You probably don’t know anything at all about what your back looks like whatever the sky holds: sunlight, moonrise. I rest there. My hand, my eyes, my mouth. The first time I see it you are shaping fire with bellows. The shine of water runs down your spine and I have shock at myself for wanting to lick there…There is only you. Nothing outside of you. My eyes not my stomach are the hungry parts of me. There will never be enough time to look how you move. Your arm goes up to strike iron. You drop to one knee. You bend. You stop to pour water first on the iron then down your throat. Before you know I am in the world I am already kill by you. My mouth is open, my legs go softly and the heart is stretching to break.

At the outset, let’s recognize Toni Morrison as one of the greatest writers of lust in the language. When Florens describes the blacksmith’s back or “that place under your jaw where your neck meets bone, a small curve deep enough for a tongue tip but no bigger than a quail’s egg,” his body is alive and electric. Each description is charged with her insatiable need to devour him. Which makes it all the more brutal when she finds him and he wants none of it.

The shock of his refusal sends Florens into a clawing rage. After (nearly?) murdering the blacksmith with a hammer, she returns to the Vaark farm and closes herself off in a house left to the ghosts. With the tip of a metal nail she scratches her story into the walls, the ceilings, the floorboards, until “there is no more room in this room.” She sleeps with her words. She considers burning down the house and letting those words rattle the sky and snow down as ash. It’s a fragile history and an epitaph of her tender life.

This is a very different notion of history than the one we see in Wolf Hall, which animates the history of the permanent. A Mercy gathers the whispers in woods, graveyards, and ancient homes. The breadth of Mantel’s project necessitates a faster pace, whereas the depth of Morrison’s requires stillness to process everything in the moment. I have a strong bias for the latter. However, it’s not enough for me to render a decision.

I think there are some people who judge books by the splendor of the highs and others who judge by the cringiness of the lows. This is probably something best saved for a therapist, but I judge my own work by the lows and the work of others by the highs. So I’m going to take the highest moment from each novel and ask myself which one made me feel more. For Wolf Hall, that’s the immolation of the Loller. For A Mercy, it’s Florens holding a lamp in one hand, carving letters with an iron nail with the other in a room covered with her life’s testament.

To me, that’s no contest. One image resonates and ramifies, causes me to reconsider every page of what I just read. A Mercy has created a living moment. I don’t consider it strictly fictional. To me, that’s a high-water mark that Wolf Hall doesn’t match. While Mantel shows us brilliantly what it feels like to watch someone burning at the stake, Morrison shows us what it feels like to be burning at the stake.

Match Commentary

By Brandon Lueken & Rosecrans Baldwin

Rosecrans Baldwin: Today we’re welcoming ToB fan Brandon Lueken into the commentary booth. Brandon, how long have you been following the ToB?

Brandon Lueken: I started following the Tournament of Books in 2010 (the year of Wolf Hall, RIP), and have been a follower ever since. I’ve evangelized the Tournament’s charms to friends and family through the years, and a few friends have joined me to follow the Tournament. I grew up in sunny Southern California, but came to the Pacific Northwest for college, and it’s been my home ever since. I live in Seattle, and work as a grant writer for a local community college.

Rosecrans: What kind of reader are you, outside the ToB?

Brandon: I’d describe myself as curious. I try to read diversely. Since I graduated college, I’ve kept an annual list of all the books I’ve read, which has evolved into a spreadsheet. There, I track the race, gender, and country of origin of the authors, as well as the main characters’ race and gender. The hard data helps keep me honest about what I’m reading. In 2017, to challenge myself, I swore off straight white men, and read more diversely, which was a good experiment into confronting my biases for white guys. I realized I was most frustrated by them as a group, and really have read more diversely since.

Over the past few years, I’ve returned to reading the genres I read a bunch of growing up: fantasy, science fiction, and graphic novels. I’m still reading literary fiction, nonfiction, and essays, but in this given moment, escapism and imagination are deeply attractive because it’s not [gestures at everything]. I’ve also been encouraged because those genres have diversified since I was a preteen, and now you’ve got N.K. Jemisin, Ann Leckie, Molly Tanzer, and many others living up to the original conceits of fantasy and sci-fi: exploring alternate visions of our society, imagining what could be by exploring extrapolations of our power structures or their absence. In their own way, these genres can be very hopeful, which is both encouraging and necessary in these times.

Rosecrans: Very much agreed. So, Judge Chancellor has given us a lot to work with here. Obviously he had deep connections to both books, but when he writes “A Mercy has created a living moment. I don’t consider it strictly fictional”—that seems like no contest to me. What did you think?

Brandon: Chancellor did say Mantel was going to have to out-Morrison Morrison, so the Brit was at a disadvantage at the start. Though, Chancellor gives us a ton to examine and explore in this judgment as he wrestles with two writers who can write powerfully about those interior moments he relishes.

But Wolf Hall and A Mercy are about very different things, written in very different styles. In one, a man rises from the literal muddy street (gutters didn’t even exist yet) to the power behind the throne that ultimately changes history. A Mercy explores the very limited agency available to women in precolonial America, which Chancellor draws out with that “servant, prostitute, wife” quote and the ways in which history has ignored or never recorded these women. Morrison’s writing becomes a kind of testament to those who were never recorded, something she did over her whole career.

So then, for Chancellor, it comes down to what he values as a reader: indelible images. With both of these novels, the images, language, themes are all working in concert to create those living moments that stretch beyond the fictional to become memories and experiences that live with us forever, that become more than fictional, changing how we think about ourselves and our relationship to the world. I think both books achieve these moments, but for Chancellor, it’s A Mercy that is more successful with the images. I don’t think of myself as an image reader much, or a quote person; I tend to be a plot/story person, though images sink into my brain. What about you, what do you find yourself taking away most often from your reading?

Rosecrans: What lasts for me, I think, is the impression of an interior sense of thought. That feeling when an author’s mind about their story sort of glows through the text. The sense they spent years and years figuring something out, and the something is that burning, unseen-but-felt center of the book. And I remember thinking both of these books have it intensely.

Chancellor focuses on the importance of “the highs” when he’s measuring a book’s value. That focus on excellence, is that something you relate to? How might you have chosen in this matchup?

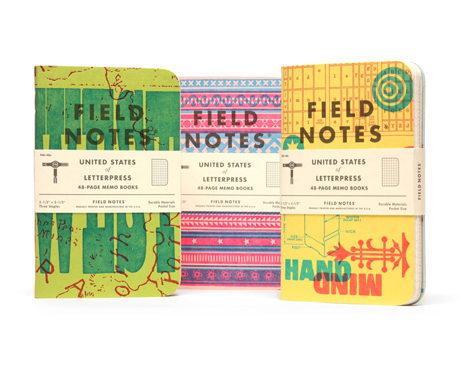

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.

Field Notes® Limited Edition for the Fall of 2020 is the “United States of Letterpress,” which features the work of nine independent letterpress shops from across America. This series demonstrates a wide array of craftsmanship, ingenuity, and love for the age-old and tactile process of letterpress printing. Check the the short documentary film too.Brandon: I do relate to the excellence of books, because that gets back to what the whole ToB is about: comparing the relative merits of books. Both Kevin and John have talked at length over the years about how to recommend a book to someone, how you present it, identifying its strengths and matching it to the prospective reader. When you make a recommendation, you have to explain “why this book is good.” It’s a bit of an art to summarize something in a way that tantalizes. You can emphasize the imagery, the writing, or how fast you devoured it because the book was just plot-plot-plot.

When I think about the books in play, I do think about “the highs,” and if a book has appropriately set up those highs. For me, these two books are excellent, but for very different reasons. I was very deeply moved by Wolf Hall. I don’t cry at books hardly at all, but Mantel brought me to tears when describing how Cromwell loses his youngest daughter and his wife to illness in just a few short paragraphs. That sticks with me, as does Cromwell “costing out” various members of court, rattling off the yardage and worth of their sumptuous clothes.

Rosecrans: Oh, I loved that.

Brandon: There’s an expertise, a level of control in Cromwell that I think is engaging and mesmerizing. Mantel emphasizes that control with the use of “He” in the novel, too, referring to Cromwell often as just “he”, but also the royal “He” of King Henry VIII. Readers can be confused about which “He” Mantel is referring to, but I think that is an intentional choice because Cromwell seeks to collapse the two, to represent and maneuver the King in such a way that his suggestions represent the King’s word, and the power of the throne. Ultimately, we know that’s a gambit that Cromwell loses, but Wolf Hall’s language and images stick with me, years and years after I originally read it.

I began reading A Mercy for the Super Rooster, and I struggled a great deal with this particular Morrison book because of how she has unpinned time. I found the narrative confusing, and difficult to really latch on to any particular character. Yet, I think the overall aim of Morrison’s novel is to explore power structures in such a different way than Mantel. Chancellor mentions it in his judgment, how A Mercy explores the power structures of society, and how race and gender have shaped these women’s lives. The scraping of a life story on a wall with a nail is a powerful image, a literalization of claiming your own autonomy and power. For such a slim book, it engages with some meaty material.

While Morrison is no longer the only American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature since the 1990s, I am reminded of a quote from the Nobel committee that I read some years ago that described American letters as relatively provincial, uninterested in the broader concerns. I didn’t understand the criticism in full when I read it. Though, earlier this year, I read Jess Row’s book of literary criticism White Flights: Race Fiction, and American Imagination, and now I feel like I better understand that criticism. Row points out that many of our most celebrated literary authors like Don DeLillo, David Foster Wallace, and Marilynn Robinson aren’t terribly interested in fully engaging with the race, whereas Morrison constantly engages with those elements in a meaningful way with transportative narratives. Yet, I think A Mercy is a book that I connect with on an intellectual but not emotional level. For me, Wolf Hall is a book that I connect with on both levels, and is the book I would have chosen.

Rosecrans: Yeah, I hear that. For my part, I connected with both books on both levels. Then again, the last book that made me cry was Stamped From the Beginning.

The judge tells us in this first line how foolish this exercise is—essentially, a point the Rooster has made for pretty much all of our 16 years. Where do you find value in this shenanigan?

Brandon: The value for me is in the community, the discussion of books. Like I mentioned earlier, I tend to read diversely, so while I could talk about graphic novels and sci-fi with friends who share those interests, the ToB has been a place for me to read and talk about other literary books. The Rooster has been a great place to read about other people’s reactions to books, to get recommendations for new books, to engage in some deep but also fun and arbitrary literary criticism discussion.

It’s foolish, but it’s also art; it takes on the amount of meaning that we give it, be it a lot or a little. Reading a good book is a bit of alchemy, and some things just hit differently, depending on when you read them or what you just read, or what else is going on in your life. I think like many other readers, I can’t separate the reading pleasure of a good book without including the circumstances. I remember with visceral pleasure being 12, tucking into a freshly purchased Redwall book on a warm summer night eating deep red cherries. And also the coldness of my apartment as I was too engrossed reading Jesse Ball’s Silence Once Begun for the ToB in 2015 to turn on the heat. Now, it’s a novel I associate with coldness, the cold apartment matching the suppressed emotions in that book. The ToB gives little windows into other people’s habits as readers, their views, and that’s valuable. The good discussions and observations make me want to keep reading and keep participating in the ongoing discussion around literature and the stories we tell.

Rosecrans: Cheers to that! Many thanks to Brandon and Judge Chancellor. We’ll see you all in the comments, then back here tomorrow for Roxane Gay deciding between A Visit From the Goon Squad and The Sisters Brothers.

New Super Rooster merch is now available at the TMN Store. As a reminder, Sustaining Members receive 50 percent off everything in our store. To find out why we’re asking for your support and how you can become a Sustaining Member, please visit our Membership page. Thank you.

Welcome to the Commentariat

Population: You

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

- Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

- If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

- While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus

tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “ Dumbledore dies .” - We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.